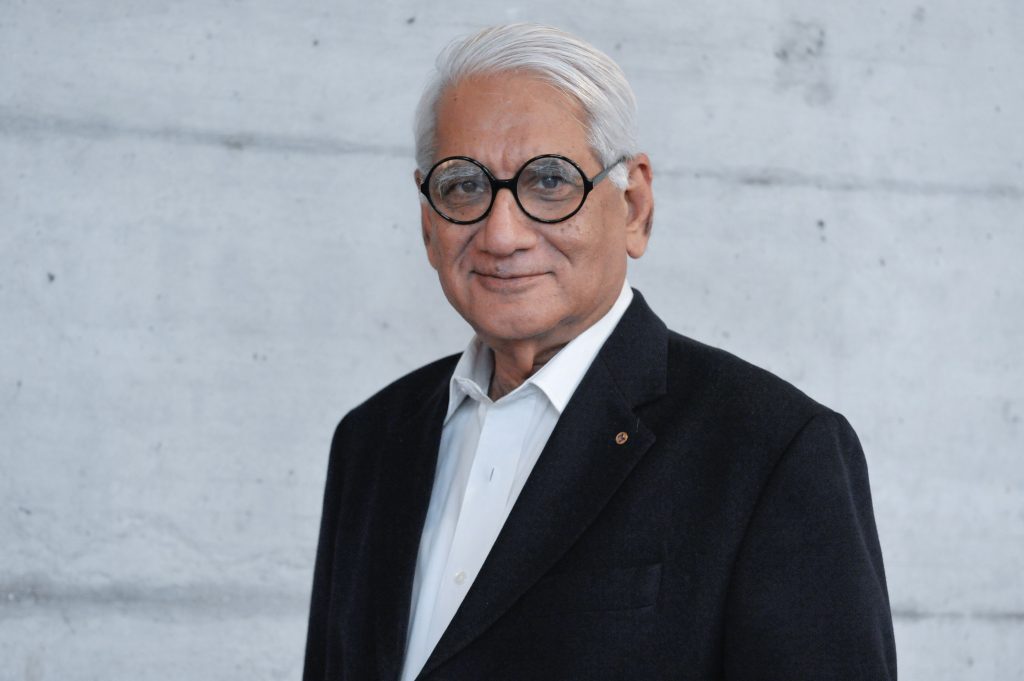

Charles Correa (1930–2015), one of the most important and celebrated architects of India, practiced architecture and urban planning for over five decades. Born in Secunderabad, he studied at the University of Michigan and MIT, blending Modernist principles with local climates, materials, and social needs. His work addressed India’s post-independence challenges, prioritizing affordable housing, energy efficiency, and community scale over high-rises.

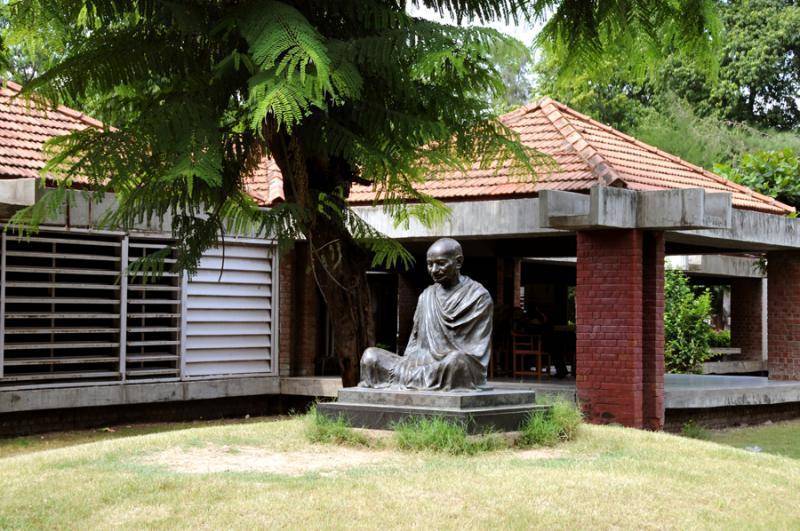

Correa’s early projects emphasized site sensitivity and climate response. The Gandhi Smarak Sangrahalaya (1958–63) in Ahmedabad integrated with topography using open courtyards and natural ventilation. In Delhi’s Handloom Pavilion (1958), he employed lightweight roofs and shaded spaces to combat heat. Residential designs like the tube houses in Ahmedabad—Ramkrishna House (1962–64) and Parekh House (1966–68)—featured narrow forms with verandas for passive cooling in arid conditions.

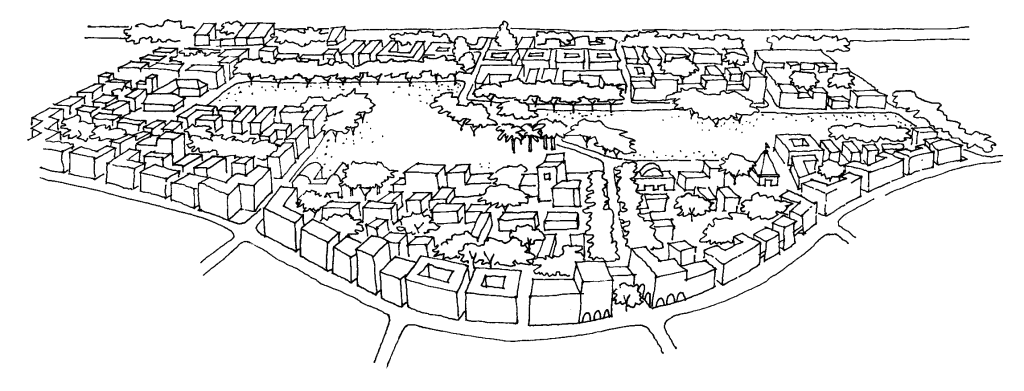

Urban planning defined Correa’s mid-career impact. As Chief Architect for New Bombay (1970–75, now Navi Mumbai), he planned a satellite city for two million residents, focusing on low-rise clusters with open spaces to foster community and jobs. The Belapur housing (1983–86) in Navi Mumbai used incremental low-cost units mimicking rural patterns amid urban density. He avoided skyscrapers, favoring human-scale environments with facilities like markets and schools integrated on-site.

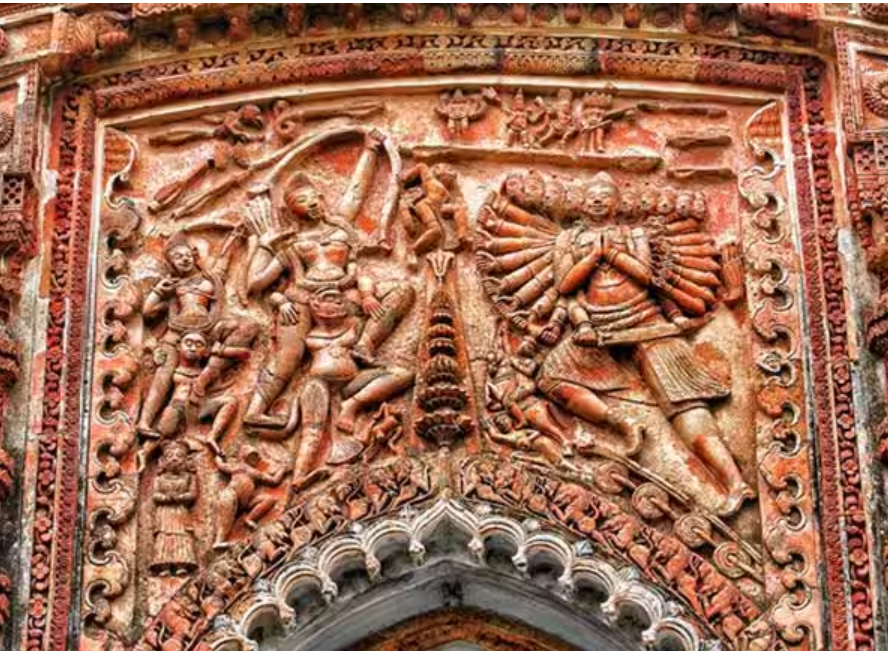

Later works showcased evolving techniques. The Jawahar Kala Kendra (1986–93) in Jaipur drew from traditional Rajasthani forts, organizing nine squares around a central courtyard for cultural functions. In Delhi, the National Crafts Museum (1975–90) featured “rooms open to the sky”—courtyards blending indoor-outdoor spaces. The Jeevan Bharati towers (1986) combined red sandstone cladding with a massive pergola for shade. Internationally, he designed MIT’s Brain and Cognitive Sciences building (2005) and Toronto’s Ismaili Centre (2014).

Correa founded the Urban Design Research Institute (1984) in Mumbai to study urbanization. He chaired India’s National Commission on Urbanisation (1985–88) and advised Goa’s government from 1999. His practice influenced policy on shelter for the urban poor, using parasol roofs, courtyards, and local materials like brick and stone. Key themes included tropical adaptation, incremental growth, and cultural continuity, shaping India’s architectural identity.

Athmaja Biju is the Editor at Abir Pothi. She is a Translator and Writer working on Visual Culture.