Custom Design Stories is a vision built on the idiosyncrasies of curious minds. The team experiments, dares, designs, and remains absorbed in what they do while appreciating the work being done all around them. The studio engages computational and material intelligence, and spatial explorations with colour as operative design variables, as it surfaces from the educational specialisation of Aditya Tognatta.

After completing his bachelor’s at the School of Architecture and Planning, Delhi (erstwhile the TVB School of Habitat Studies), Aditya pursued his M.Arch in Emergent Technologies at the Architectural Association, London. Here, rigorous discourse with architects, engineers, and technologists shaped a pragmatic, systems-driven approach to translating digital logic into physical outcomes through prototyping and robotic fabrication.

He was joined by Ananya Sharma, who brings a decade-long experience in architecture and chose to take the road less taken. Her exposure to the diversity and multi-disciplinarity of a startup environment allowed her to wear multiple hats at the company leadership level.

Together, Aditya and Ananya work like pieces of LEGO, completing the picture of running a studio efficiently and imaginatively.

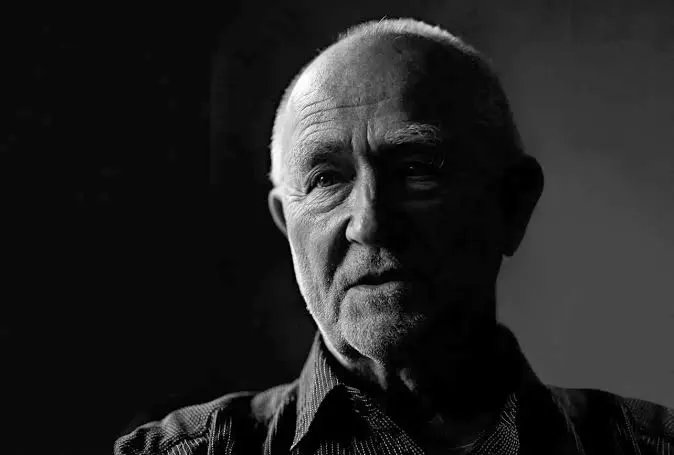

In this insightful conversation as part of Abir Pothi’s DTalks, showcasing the best of design and architectural innovators of India, Aditya Tognatta reveals his design process, philosophy and learnings over the years.

Q. How would you describe your signature design aesthetic, and how has it evolved while working in India?

Aditya Tognatta: Well, describing my “signature aesthetic” feels a bit like trying to debug a spaghetti script someone else wrote — amusing, occasionally painful, but revealing in the end. If I had to compress it loosely: the simplest code is the best code.

Not minimalism — that’s too romantic. More like… parametric austerity with intent.

So, what has evolved are the techniques, architectonics– the essence remains intact, a kind of controlled algorithmic realism. Clean logic wrapped around messy contextual constraints. A stubborn refusal to add anything that doesn’t serve a function. And yes, a not-so-subtle influence of anime, Japanese pattern logic, and game-world spatial rhythm — because nothing teaches proportion better than a well-designed boss fight arena.

Q. What influences and inspires your current work? Could you share some movements, designers, or elements of Indian culture that have shaped your practice?

Aditya Tognatta: Being a young design firm, we’re apparently required to exude “high energy” at all times. And yes, the studio is buzzing—though most of that energy goes into swatting away the endless stream of digital kitsch masquerading as “inspiration.” At CDS, we’ve long accepted a basic truth: meaningful design is less about adding brilliance and more about subtracting nonsense. Reduction isn’t a philosophy for us; it’s self-defense.

My own influences are a bit of a mixed bag—anime, Japanese art, gaming patterns, machines, engineering. Not exactly the canon your architecture professor would approve of. But these were never guilty pleasures; they quietly became my internal operating system for rhythm, proportion, colour, drama. A private codebase that somehow made more sense than most architectural textbooks.

At CDS, material sits firmly at the center of design. It’s the message, the mood, and sometimes the entire argument. You can Photoshop anything into looking profound, but a material doesn’t lie. It will tell you—politely or otherwise—what it wants to be.

On the slightly more serious, “architects-pretending-to-be-philosophers” side of the spectrum, Zumthor and Pallasmaa have shaped how I think about sensory experience: the weight of a material, the temperature of a surface, the slow acoustics of a room. Their devotion to slowness is a necessary antidote to today’s hyper-productive, hyper-forgettable building culture. They remind me that spaces should be lived, not merely photographed and posted with a pretentious caption.

I’m also drawn to the critical mischief-makers of design—Sottsass questioning rationalist purity, Cedric Price wondering if architecture should even bother being permanent, and James Turrell, who basically builds with light and dares you to call it architecture. They collectively nudge me to stay suspicious of easy answers and to ask “why” long before “how.”

But some of my deepest influences come from India—not just architects, but artists and the broader cultural ecosystem.

Nek Chand’s intuitive, resourceful worlds quietly argue that Indian design has always thrived on improvisation and constraint. And Gaitonde’s disciplined abstraction teaches a kind of minimalism that isn’t cold, but meditative—proof that restraint can still have a pulse.

In my current work—residential projects, community spaces, clubhouses—all these threads meet somewhere in the middle. The attempt is always the same: to find that equilibrium between rigor and softness, precision and the beautifully informal. Not to imitate these figures or movements, but to keep alive the critical tradition they embody: design with intention, question with sincerity, and make spaces that feel relevant without surrendering their roots.

Q. Could you walk us through your creative process? How do you move from initial concept to final execution?

Aditya Tognatta: My creative process is not a mystical pilgrimage. It’s mostly disciplined chaos held together by caffeine, experience, and the occasional stroke of clarity.

I start by listening, because—unfortunately—architecture still has to solve real problems for real people. Clients tell you what they want; you decode what they actually need. These are rarely the same.

Then I look at the site and context. Climate, culture, craft… all those things we pretend are optional until they come back to bite you in the façade. India, at least, is generous—light, materiality, and a certain cultural looseness always give you something to work with.

The concept stage is basically me asking a question that annoys the team: “What if we tried something that actually makes sense?” This usually produces a direction: a spatial idea, a behavioural insight, or a problem worth solving.

From there, it’s an endless cycle of iteration. Sketch, model, test, throw half of it out, pretend this is “creativity,” and continue until something stands up structurally and emotionally.

Materials enter the picture once the idea stops wobbling. Texture, light, and acoustics are chosen like casting a film—everyone must play their role without demanding too much attention.

After that comes coordination with engineers, where idealism meets gravity, plumbing, and other inconvenient truths. Then detailing, which is simply the art of making sure your idea survives the contractor’s enthusiasm.

Finally, execution. This step involves answering the same question 900 times, visiting site, and ensuring the building doesn’t slowly mutate into something unrecognisable.

And that’s it.

Nothing mystical.

Nothing romantic.

Just the slow, stubborn act of dragging an idea from possibility to reality—and making sure it doesn’t embarrass you once it’s built. And maybe, just maybe, I can buy that manga, which has been missing from the many volumes I am yet to buy – complete my collection.

Q. Your work often involves collaborations with artisans and other creatives. What draws you to these partnerships, and how do these collaborations enrich your design practice?

Aditya Tognatta: Ah, collaborations.

People imagine they’re these poetic, candle-lit exchanges between “the designer” and “the artisan,” both nodding in philosophical agreement while discussing the metaphysics of a hand-woven joint. In reality, what draws me to these partnerships is far simpler: they know things I don’t, and they do things I can’t. And I’ve learned it’s far more intelligent—and frankly efficient—to stand next to people who are brilliant at their craft, rather than pretending I can Google my way into centuries of mastery.

India, fortunately, spoils you.

You turn a corner and bump into someone whose family has been perfecting one microscopic technique—stone inlay, metal casting, lime plaster, weaving, joinery—for generations, and they’re still better at it on a Monday morning than most of us are on our best day. Collaborating with them keeps the work honest. It keeps it grounded. And it prevents me from drifting into the great global soup of “design that could belong anywhere and therefore means nothing.”

Working with artisans also forces a kind of discipline: the material talks back. It has opinions. It resists. It misbehaves. And when it does, the artisan is the first to raise an eyebrow and tell you, quite politely, that your “brilliant idea” may be architecturally sound but is practically ridiculous. That tension—between imagination and reality—is where the good work happens.

So yes, collaborations enrich my practice.

Not in the romanticized brochure way, but in the quietly essential way: they keep the work culturally rooted, technically sharper, and, most importantly, they ensure that the project has a soul that can’t be mass-manufactured or copy-pasted.

And if nothing else, they save me from believing my own press—which might be the greatest enrichment of all.

Q. Looking back at your portfolio, which project represents a significant turning point in your career, and among your recent works, what project are you most proud of and why?

Aditya Tognatta: Looking back, the real pivot in my career was Mahindra Luminare, a 4000 sq ft penthouse that started as a project and ended as a friendship. It was my first work under my own moniker, which meant every decision—good, bad, or ill-advised—was entirely mine. A liberating and mildly terrifying revelation.

The home essentially became a testing laboratory masquerading as a residence. We designed everything—light fixtures, furniture, the tiny details people only notice when they try to copy them. If it existed in that house, chances are we obsessively prototyped it and briefly regretted our ambition.

A personal favourite act of heresy was the Italian marble staircase. Most people treat marble like a sacred relic; we painted over it with seven layers of colour, so that as it ages—and age it will—you begin to see soft gradients emerging, almost like rainbows resurfacing through time. Conservationists would faint; we took it as a good sign.

Then there was the infamous sea-green envelope—walls immersed in a colour most Indian families would reject on sight. But we leaned in. The client trusted us, and the result was a space that felt calm, moody, and blissfully uninterested in the tyranny of beige.

We also created a handcrafted mandala with a local artist—not the usual spiritual sticker-treatment, but a layered artwork that became the emotional core of the home.

I’m proud of Luminare not because it was smooth sailing, but because it was the first time the studio’s voice stopped whispering and decided to speak plainly. It proved that experimentation—handled with sincerity, precision, and a touch of audacity—can actually hold its ground. Sometimes it even becomes a home people love.

Q. What unique challenges and opportunities have you encountered as an emerging designer in the Indian design industry, and how are you working to overcome these obstacles?

Aditya Tognatta: The Indian design industry has its own charming ecosystem: too many architecture schools producing too few genuinely hireable architects, and an almost comical ease with which anyone can open a “studio.” The result? A marketplace flooded with undertrained designers undercutting fees so aggressively that survival itself becomes a design problem.

As an emerging practice, the challenge isn’t inspiration — it’s maintaining standards while swimming in a sea of discounted mediocrity. Low fees drag down margins, push timelines into absurdity, and make quality feel like a rebellious act.

But there’s opportunity in the chaos. When the bar is set this low, doing things properly becomes a competitive advantage. So I keep the team small, train slowly, and take on clients who value design more than discounts. We focus on craft, on material truth, on details that can’t be faked in a mood board.

In a landscape obsessed with quantity, the only way forward is to insist — stubbornly, almost irrationally — on quality. It’s slower, yes. But it’s also the only path where the work stands up, and the studio stands out.

Q. How do you approach sustainability and eco-friendly practices in your designs, particularly considering India’s traditional wisdom and contemporary environmental challenges?

Aditya Tognatta: The Indian design industry is a fascinating place — if you enjoy chaos. We have an oversupply of architecture schools and an undersupply of actually hireable architects. Add to that the delightful ease with which anyone with a laptop and a half-baked Pinterest board can start their own “studio,” and suddenly you’re competing with an army of undertrained designers offering bargain-basement fees that could make even a charitable trust blush.

For a young practice, the real challenge isn’t creativity, it’s maintaining dignity while everyone around you is racing to the bottom. Lowballing has practically become a national sport, and the collateral damage is quality, margins, and occasionally, your will to live.

But here’s the upside: when the baseline is this low, doing things properly becomes radical. Almost subversive.

So we keep the studio intentionally small. We hire carefully, painfully so. We train people who actually want to learn, not just download more “references.” We work with clients who appreciate design, not discounts. And we obsess over craft and materiality because, in a market obsessed with speed, patience itself becomes a signature.

In the end, the strategy is simple:

In an industry built on shortcuts, take the long road.

It’s slower, less glamorous, occasionally exasperating, but it’s also the only way the work feels honest, and the only way the studio stands out without shouting.

Q. What’s your most exciting recent design or art discovery that’s influencing your current thinking?

Aditya Tognatta: My most exciting “recent” discovery isn’t remotely recent, it’s something we’ve been quietly developing for over two years. We’ve been working on a new hybrid glulam made with bamboo for mass-timber construction, originally for an eco-resort in the Himalayas. It’s not glamorous work; it involves endless testing, simulations, failed prototypes, and long conversations with structural engineers about why gravity remains undefeated.

We’ve run both digital and physical tests, stress, moisture, thermal behaviour, creep, weathering, and, against all odds, the results are genuinely promising.

What makes this exciting is not just the prototype itself but what it could mean. We’re envisioning a material system that could replace the way buildings are made in the hills altogether, moving away from wasteful RCC boxes and towards something lighter, renewable, and actually suited to the terrain. A small ambition, really: just rewiring an entire construction culture.

It’s influencing my current thinking because it’s a reminder that innovation doesn’t arrive with fanfare. It’s slow, stubborn, and occasionally exasperating. But when a material starts cooperating with you, even a little, it opens up the possibility of changing more than just a single project.

Q. How do you build visibility and reach out to potential clients – what platforms and strategies have worked best for you?

Aditya Tognatta: Visibility in architecture is a strange game. Everyone pretends it’s about “the work speaking for itself,” but the work usually whispers while the algorithm shouts. So yes, we do the necessary dance — just with as much dignity as possible.

We’ve learned that quality clients don’t come from scatter-shot marketing; they come from seeing something you’ve built and thinking, “Ah, these people care.” So our primary strategy has been painfully simple:

Do good work, finish it well, and let the built project be the loudest advertisement.

That said, we’re not hermits.

- Instagram has been useful, but only when treated like a portfolio, not a circus. We post selectively, projects, materials, and processes. No motivational quotes, no time-lapse reels of us pretending to sketch dramatically.

- Long-format features , the occasional publication, journal, or design portal — tend to attract clients who actually read (a rare but appreciated species).

- Talks, panels, and juries help too, mostly because they filter in people who value design enough to show up in person.

- And then there’s the most powerful platform of all: clients telling other clients. It remains undefeated.

In short, our strategy is to stay visible without being noisy.

If the work is thoughtful, it travels.

If it isn’t, no amount of hashtags can save you.

Q. From your experience, what are the crucial dos and don’ts for young designers trying to establish themselves in India, and what professional forums or communities would you recommend they join?

Aditya Tognatta: For young designers trying to establish themselves in India, the first rule is simple: don’t lose your playfulness. The industry will try very hard to sand it off , with budgets, deadlines, and the occasional client who believes “creative freedom” means changing the wallpaper. Guard your curiosity like a rare mineral.

The second rule is to have a vision, an actual one. As I.M. Pei said, “You must have a vision. If you don’t, you’ll be lost in the details.” And India has no shortage of details to get lost in: contractors, consultants, permissions, neighbours, and relatives with unsolicited opinions. Your vision is the compass; everything else is noise.

And then comes the most unglamorous virtue: patience. Not the meditative, Himalayan retreat kind, more like slow, stubborn endurance. Projects take time. Good clients take time. Good teams take even longer. Move forward anyway.

As for the dos and don’ts:

Do:

- Build your own voice, even if it’s still cracking.

- Care about materials and craft; they age better than trends.

- Learn to listen — to clients, to craftsmen, to your own doubts.

- Show up consistently; reliability is more radical than you think.

Don’t:

- Don’t underprice yourself “for experience.” It only teaches clients to expect discounts.

- Don’t imitate other studios; India already has enough mood-board architecture.

- Don’t chase visibility at the cost of substance — the algorithm is a fickle god.

- Don’t let cynicism outgrow curiosity.

Q. As you look ahead, what kind of projects or directions would you like to explore?

Aditya Tognatta: We’re interested in architecture that lasts, adapts, and matters— not buildings that photograph well and then fade. That means floating, resource-based settlements, because eventually, everything will drown, and yachts or water-based transport systems as experimental platforms. The goal is simple: design for time, context, and survival, not for applause. Everything else is just decoration.

Q. For aspiring designers looking to make their mark in India’s design landscape, what wisdom would you share from your journey?

Aditya Tognatta: DON’T assume you know and DO the real work. Have a community of mentors and peers who engage you and provoke you- For the Instagram generation.

Athmaja Biju is the Editor at Abir Pothi. She is a Translator and Writer working on Visual Culture.