Between 1962 and 1965, the Second Vatican Council ushered in liturgical reforms emphasizing participation and clarity, freeing Italian architects from rigid typologies to create bold, modernist sacred spaces. Postwar Italy’s economic boom, urban sprawl, and secular shift met Vatican II’s call for renewal, birthing experimental churches that anchored new communities. Marta Minuzzo’s “Templi Moderni. Costruire il sacro in tempi distratti” captures this era’s transformation through photography. These buildings became cultural devices, blending faith with modern life.

Five Iconic Examples

Discover five striking churches that redefined sacred architecture amid Italy’s rapid change.

1. Gio Ponti’s Fopponino Church, Milan

Built in the early 1960s for a growing peripheral parish, Ponti’s church of San Francesco d’Assisi in Fopponino answered Archbishop Montini’s call for “22 churches for 22 councils”, tying liturgical renewal to urban expansion.

Its architecture works as a compact urban hinge: a sculpted volume that organizes courtyards and passages, making the church not a distant monument but a porous presence woven into everyday circulation.

Inside, space is gathered closely around the altar, translating Vatican II’s emphasis on participation into a near-domestic scale where congregation and presbytery visually and acoustically share the same room.

2. Co-Cathedral Gran Madre di Dio, Taranto

Completed in 1970, Ponti’s co-cathedral stages a radically stripped-back sacred language, replacing ornament with a few monumental gestures tuned to Taranto’s port and Mediterranean light.

A perforated façade filters sun and sky, turning light into the main liturgical material; reflected in a forecourt pool, the building hovers between ship, screen and abstract reliquary.

Instead of axial procession through baroque depth, the co-cathedral composes a frontal, iconic silhouette, working as a civic landmark for a rapidly modernising city as much as a devotional interior.

3. Alvar Aalto’s Santa Maria Assunta, Riola di Vergato

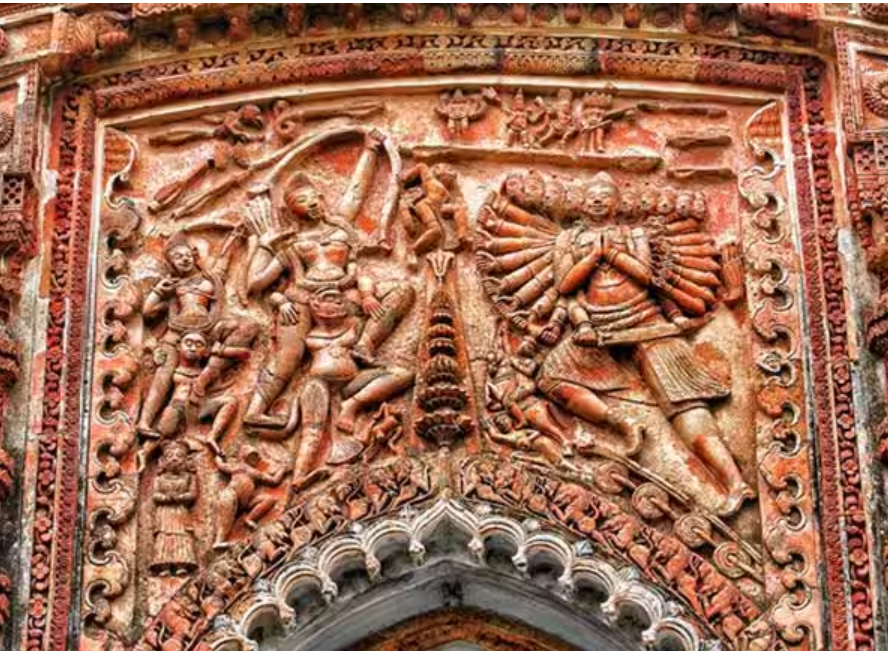

Designed in the 1960s and built in the 1970s, Aalto’s only Italian church translates Nordic modernism into an Apennine valley, using concrete ribs and soft daylight to shape a quiet, topographical nave.

The roof’s rhythmic, sail-like sections capture and wash light down the walls, making the liturgical focus emerge from gradations of brightness rather than heavy iconographic programs.

A large forecourt blurs the line between church and village square, so the building becomes the armature for community gatherings, reflecting the idea of sacred architecture as a civic “device” in a semi-secular landscape.

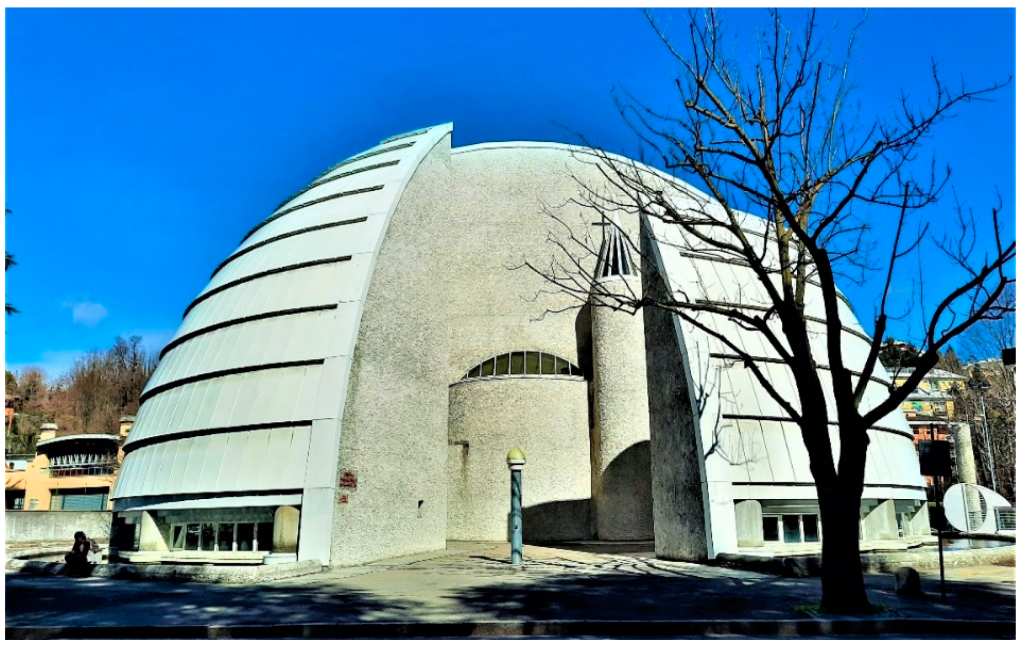

4. Justus Dahinden’s San Massimiliano Kolbe, Varese

Set along one of Varese’s busiest roads at the edge of the Milan metropolitan area, Dahinden’s church appears as a single enormous white dome, somewhere between tent, hill and spacecraft.

The pure volumetric form replaces historical façades and bell towers, using the curve and its stark whiteness to announce a sacred pause within the flux of traffic and suburban sprawl.

Inside, the continuous centralised space gathers the community under one canopy, echoing post-conciliar liturgical thinking where the assembly, not linear procession, structures the church’s geometry.

5. Mario Botta’s Church of the Holy Face, Turin

Built in 2004 on Turin’s post-industrial axis Spina 3, Botta’s church occupies a landscape of redeveloped factories, reading almost like “the first of the factories” in its mass and brick rigor.

Cylindrical and prismatic volumes interlock to form an austere, fortress-like body; the material heaviness underlines the church’s role as an anchoring reference point amid urban regeneration.

Here sacred architecture behaves less as a village hearth and more as a symbolic condenser at metropolitan scale, mediating between the memory of production, the present of secular life, and the ritual of gathering.

These five “modern temples” show how Italy’s churches after Vatican II shifted from repeating typologies to negotiating new rituals, peripheries and publics—precisely the narrative Minuzzo’s series brings into focus

Athmaja Biju is the Editor at Abir Pothi. She is a Translator and Writer working on Visual Culture.