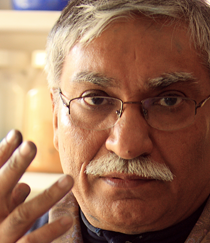

Sidharth

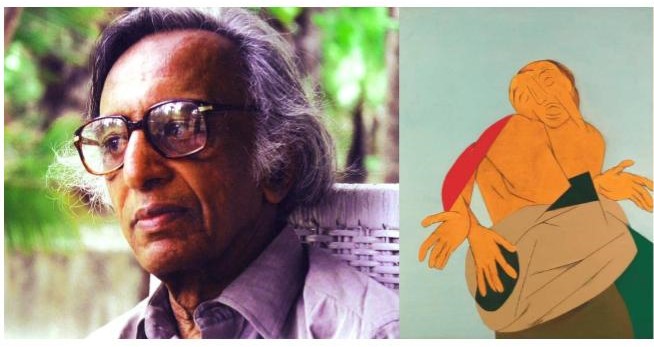

On the centenary of Tyeb Mehta’s birth, contemporary artist Sidharth reflects on a profound encounter with the master painter that revealed the deeper spiritual and philosophical dimensions underlying Mehta’s iconic diagonal compositions. In this deeply personal tribute, Sidharth—himself a multidisciplinary artist whose work bridges traditional Indian wisdom with contemporary expression—shares an intimate conversation that illuminated how Mehta’s seemingly modernist visual language was actually rooted in ancient Indic cosmology and sacred geometry.

Through this rare glimpse into the artist’s own understanding of his work, we discover how Mehta’s triangular divisions were not mere compositional devices but sacred invocations of cosmic duality—the eternal dance between masculine and feminine energies that governs creation itself.

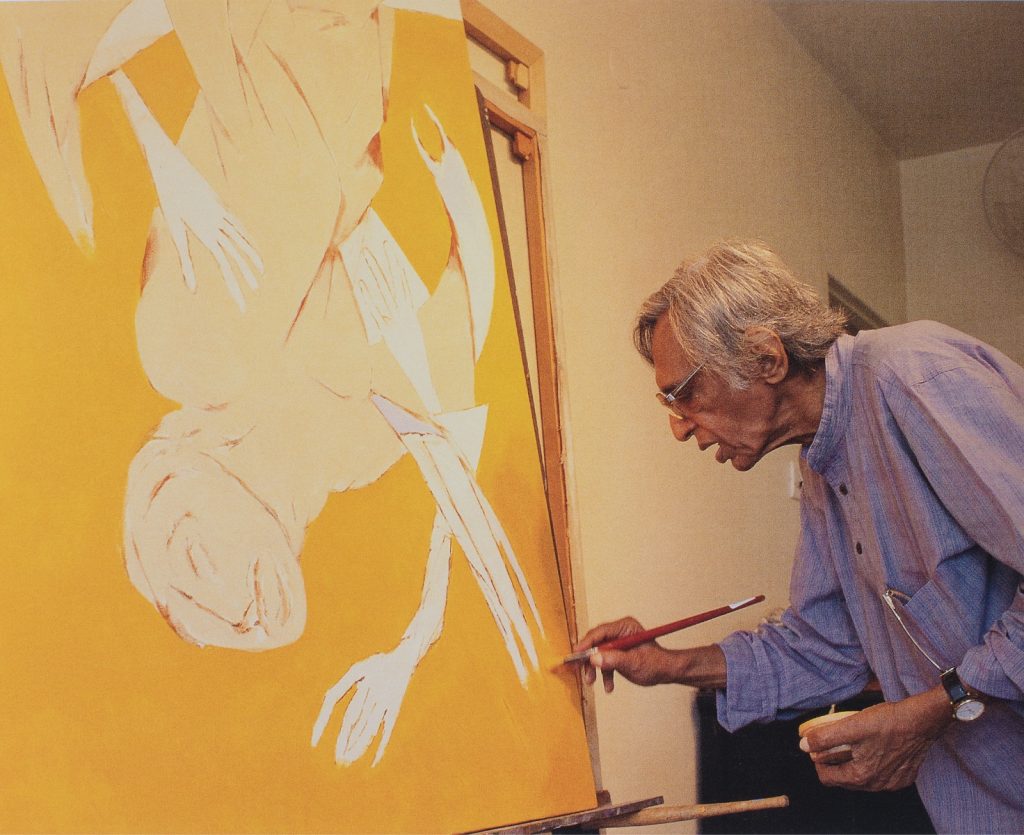

There is no need to discuss his religion, caste, or creed—his true identity was rooted in the universality of art. He was a holistic creator: a filmmaker, a storyteller, and a painter who spoke through flat planes of colour and decisive lines. He wasn’t talkative, but with just a few words—or a single stroke—he could express profound truths: the weight of war, the sorrow of division, and the wisdom of lived experience. His awareness of worldly matters was sharp, yet he chose the canvas to speak. For him, art was not a profession. Art was his faith, his language, his religion.

Through his paintings, one could hear a cry—raw and human.

A roaring deity emerged from the canvas, fierce and divine.

There was the clash of a cockfight, the violent grace of a bullfight in full force.

And amidst this chaos, if you listened closely, you could hear a music—ancient and ethereal—descending from the sky, like the first song of creation echoing through the silence.

Some critics describe Tyeb Mehta as a continuation of Francis Bacon, the British painter. Others compare him to Picasso, while some say he was influenced by M.F. Husain. Perhaps he did absorb the technical brilliance of many masters—but Tyeb was not imitating; he was transforming. He communicated his mind through an entirely new visual language, one that was deeply personal and hauntingly universal.

His paintings were often biographical visualizations—reflections of the world around him, the turmoil of his time. He bore witness to difficult histories: the trauma of displacement, the anguish of Partition, the silent suffering of human disaster. Yet, remarkably, he did not show gore or bloodshed. Without a drop of blood, he made us feel the enormity of the cry—a cry that echoes still through his restrained forms and fractured figures.

Once, I had the rare opportunity to meet Tyeb Mehta in Delhi. It was in a quiet corner of a gathering—away from the noise and art-world chatter. I gently asked him a question that had long intrigued me:

“What made you run a line through your rectangular canvas, dividing it into two triangular parts before painting those striking, broken figures? Is it just a design choice for composition? Or is it a kind of distortion—an artistic device to stand apart, as many artists often use such techniques in the name of modernism, shock value, or bohemian rebellion?”

He smiled warmly, as if amused and moved at once.

“You really wish to know?” he asked.

“I’ve answered this question many times before,” he continued, “but no one ever truly listened. No one ever cared to write about it.”

Then, pausing for a moment—perhaps taking in my presence, the robe I was wearing, the silence between us—he said with a glint in his eyes:

“Okay… I will share it with you, my dear young monk.”

He had noticed I was dressed like a Buddhist monk. And in that moment, perhaps sensing something contemplative in the air, he began to speak about his diagonal experience—not just as a compositional device, but as a deeper fracture, a metaphysical divide, a line of fate itself.

“This whole universe,” he began, “is composed of energies—some visible, many formless, and countless others beyond human perception. Let’s not speak of all that remains unknown; instead, let’s talk about the known: the play of male and female energies—the sacred balance.”

“In Indic wisdom, we speak of the trinity—Brahma, Vishnu, and Mahesh—three primary male energies. But they are not complete without their counterparts: Saraswati with Brahma, Lakshmi with Vishnu, and Durga, the fierce protector, with Mahesh. Durga herself expands into nine forms—the Navadurga, also known as the ten forms of wisdom or Dasa Mahavidyas.”

He paused, letting the silence settle.

“So, while male energies are counted as three, the feminine forces are four times more in number, infinitely expansive. They are dynamic, creative, and fierce. When I divide the canvas into two triangles, I am invoking this cosmic duality—not merely as a design element, but as a profound visual metaphor.”

“In our tradition, the triangle is not just a shape. It is a symbol—a sacred geometry of union and transformation. If you study the temples of Kashi (Varanasi) carefully, you’ll see: their entire structure is based on this triangular energy—this sacred alignment. My diagonal line is not modernist shock; it is ancient memory, rediscovered on canvas.”

If we are to speak of the feminine force, then we must mention Mahishasura Mardini—the slayer of the mighty demon Mahishasura. She is the embodiment of supreme power, the one who can destroy the most fearsome force in a single moment. Just like Kali, the great black energy—untamed, raw, and absolute—the feminine divine is not only nurturing, but also fiercely protective and transformative.

I believe you understand what I mean. And I suggest, dear Lama, that we must begin to care more deeply for Indic traditions and the timeless wisdom they carry. This wisdom is not lost—it is still alive, in our literature, our icons, our metaphors.

Unfortunately, much of our post-independence intelligentsia in India has turned its gaze entirely westward. There is nothing wrong with engaging Western thought—it is rich and expansive—but we must remain open to all forms of wisdom, especially the one rooted in our own soil. True learning is not about choosing sides—it is about recognising the light wherever it shines.

I was almost out of words. I bowed to him quietly and returned home with a heart full of gratitude.

This is what happens when you meet a truly positive, egoless, and humble human being. My faith in being an artist grew stronger that day. I was reminded that there are still artists who live like eternal students—who devote their entire lives to one path, one pursuit, carried forward by the singular force of faith.

A faith that they may one day have darshana—a vision—of a higher being, a higher form of imagination. That they might reach a state of mind beyond the noise of the world, untouched by intoxication or ego, and dwell for a moment in śūnyatā—the vast, silent emptiness that holds all potential.

In 2018, when the news broke that Tyeb Mehta’s painting had fetched the highest price at auction, it felt like a quiet revolution in the art world. My faith in art, in truthful artists, and in the sensitivity of people around us deepened. It was a reminder that there is no shortage of those who truly value art—not just for its market price, but for the silent, transformative power it carries. It affirmed that genuine artistic vision still resonates, and that somewhere, someone is always listening with their eyes open.

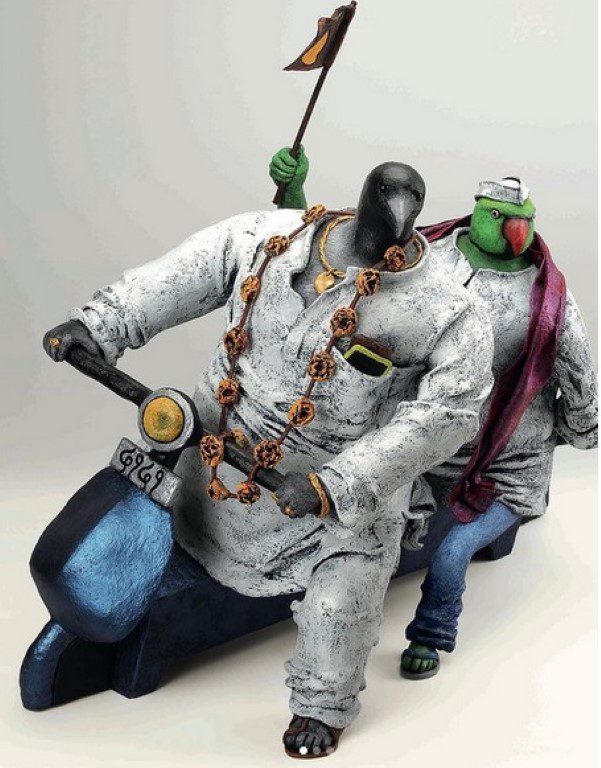

About the Author: Sidharth (born 1956) is a renowned Indian painter and sculptor whose extraordinary artistic journey spans from humble beginnings as a signboard painter in rural Punjab to international acclaim across continents. A self-taught visionary who later formalized his training with a diploma from Government College of Arts, Chandigarh, Sidharth’s unique artistic vocabulary draws from diverse influences including Tibetan thangka painting learned from monks in McLeodganj, traditional fresco techniques, and Western glass-blowing methods acquired in Sweden. Known for creating his own organic pigments from natural sources and handmade papers, his work seamlessly weaves together folk traditions with contemporary sensibilities.

His signature androgynous figures and meditative compositions reflect deep philosophical explorations rooted in various spiritual traditions. With over 135 group exhibitions worldwide and 21 solo shows across India, UK, USA, and Sweden, Sidharth’s multidisciplinary practice encompasses painting, sculpture, poetry, music composition, and filmmaking. His works are held in prestigious collections including the National Gallery of Modern Art, Delhi, and various international museums, establishing him as a significant voice in contemporary Indian art who bridges the vernacular with the universal.

Contributor