Riyas Komu occupies a rare and deliberately cultivated position in contemporary Indian art: neither fully artist nor curator, but insistently both. He is an intellectual and institutional force, constantly pushing his boundaries in reshaping how art is produced, encountered, and understood in India and the Indian Ocean world. Over nearly three decades, the Mumbai-based artist and curator has built a coherent intellectual project rooted in questions of displacement, memory, and radical coexistence.

In this conversation with Abir Pothi Editor Athmaja Biju, conducted in the context of his latest curatorial initiative Amphibian Aesthetics at Ishara House in Kochi, Komu speaks with rare clarity and conviction.

Q. You have said that the one artist who you have always been attracted to is Marcel Duchamp. How so? And what about his ideas continues to speak to your own practice and politics? In that context, how would you define art today, especially in relation to concept, context and spectatorship rather than only form or aesthetics? And finally, in your view, what is it that an artist fundamentally does—within society, within institutions, and within the shifting histories you engage with?

Riyas Komu: Marcel Duchamp has always been a foundational influence on my thinking as an artist because of the way his practice functioned as a disruptive presence within art history. What draws me to Duchamp is not simply his gestures of refusal or provocation, but the sharp intellectualism with which he dismantled inherited ideas of authorship, originality, and aesthetic value. By foregrounding the idea rather than the object, Duchamp opened up a new path for conceptual thinking—one that feels increasingly urgent in the political and social conditions we inhabit today.

In a recent work titled Fountain, I reference directly with Duchamp’s ‘Urinal’ to respond to contemporary political conditions—where repetition, appropriation, and reuse become tools for critique rather than mere citation. Duchamp’s ideas prompt me to think of art today less as a matter of form or aesthetics and more as a constellation of concept, context, and spectatorship. Aesthetics do not always help; at times, they obscure. What matters instead is how an artwork positions itself intellectually, how it is encountered, and what kinds of questions it activates in the viewer. Art, in this sense, is not about producing objects of visual pleasure but about producing moments of friction, doubt, and rethinking.

Q. Your artistic practice spans multiple mediums like painting, sculpture, installation, and video, which often engage with themes of displacement, migration, and collective memory. How do you determine which medium is most appropriate for addressing a particular political or historical inquiry? What goes into that selection?

Riyas Komu: I appreciate this question because it recognises that my engagement with multiple mediums is not stylistic but emerges from the nature of the inquiries I am invested in. Looking back, my practice has been shaped by working from and through different locations—social, historical, and material. Very early on, I became attentive to how materials carry meaning. Before formally becoming an artist, I was deeply interested in textiles and design and had aspired to study at NID, drawn to its Nehruvian ethos and its proximity to Gandhian ideas. Although I did not gain admission, a single day during the interview—where we were asked to engage with a table full of ordinary objects—fundamentally altered how I understood material. It revealed how objects open up symbolic, political, and historical registers. From then on, material became a co-traveller in my practice rather than a neutral choice.

I began my artistic career in the early 1990s, at a moment marked by profound social rupture in India. The events of 1992 became a foundational lens through which I started thinking about sites of making, displacement, and the fragility of India’s pluralistic fabric. Living through post-liberalisation, I witnessed competing ideas of progress—one oriented toward knowledge and intellectual infrastructure, and another pulling toward conservative myth-making and manipulated histories. My time in Kerala, with its investments in education, technology, and later cultural platforms like the Biennale, allowed me to juxtapose these conflicting trajectories.

As a result, the choice of medium is always determined by the demands of the inquiry—whether it requires the intimacy of painting, the evidentiary quality of archives, or the spatial and temporal complexity of installation and video. Fundamentally, my practice is driven by a desire to hold conversations between conflicting ideas, and each medium offers a different way of doing so.

Q. Your work frequently references socialist-realist propaganda aesthetics (such as Why Everybody should Look Like Mao) while critiquing nationalism and majoritarian politics. How do you navigate the tension between employing these visual languages and the ideologies they historically represented? What does reclamation or recontextualization mean in your practice?

Riyas Komu: Growing up in Kerala, I was surrounded by a dense and active field of ideological exchange. It was a place where ideas arrived from different parts of the world and were openly debated, contested, and lived through everyday social action. This history of political engagement—what I often think of as a kind of Malayali internationalism—shaped my early understanding of how ideology circulates visually and materially in public life. Kerala sustained a fragile equilibrium between multiple political positions, and that coexistence continues to inform my relationship with socialist-realist and propaganda aesthetics.

On a personal level, I grew up in a large family, and my father was shaped by socialist and Gandhian thinking. He held a firm belief in keeping religion separate from politics—religion as personal, politics as a collective civic responsibility. These values return in my work not as doctrine, but as ethical frameworks. When I reference socialist-realist aesthetics, I am not endorsing their historical ideologies. Reclamation, for me, means treating these forms as sites of inquiry—metaphors that allow us to think beyond rigid binaries. By recontextualising them within contemporary nationalist and majoritarian contexts, I aim to expose how visual languages can be mobilised, emptied, or reactivated, and to open up space for critical reflection rather than ideological closure.

Q. You co-founded the Kochi-Muziris Biennale in 2010. What was the curatorial urgency that drove this initiative at that moment? How did you envision the Biennale’s role in reshaping India’s art infrastructure?

Riyas Komu: My early years in Bombay shaped the conceptual framing for the Biennale in addition to my exposure to international platforms such as the Venice Biennale, where I witnessed how large-scale, public art projects could fundamentally reshape cultural ecosystems. Those experiences helped me imagine the Biennale not merely as an exhibition, but as an infrastructural intervention—one capable of shifting how art is produced, accessed, and debated in India.

My thinking moved from sites of conflict toward sites of reconciliation, grounded in ideas of pluralism and cosmopolitanism. Kochi was a deliberate choice because of its lived history of coexistence: within a small geographical radius, multiple communities, cultures, and faiths have historically cohabited. By 2010, there was already an organic cultural engagement in the city through spaces like Kashi Art Café and the sustained efforts of practitioners such as Anup and Dori, which allowed the Biennale to grow from an existing ecology rather than being imposed upon it.

The Biennale came further and occupied disused colonial warehouses, transforming them into sites of contemporary art production. This was an anti-colonial gesture—reclaiming spaces shaped by colonial trade and control to generate new, native narratives. We envisioned the Biennale as an open, temporal infrastructure that challenged exclusivity, metropolitan dominance, and patronage-driven models. In doing so, Kochi offered an alternative to India’s art geography, and today stands as a critical post-independence site for international art-making and dissent.

Q. Through your various initiatives at the Kochi Biennale Foundation—Students’ Biennale, Children’s Biennale, Artists’ Cinema, and Pepper House Residency—you’ve consistently worked to democratize access to contemporary art and knowledge. What was that experience like? What lessons did you take from such undertakings?

Riyas Komu: The initiatives we developed at the Kochi Biennale Foundation emerged from a very specific responsibility. Unlike many biennales that operate within already established cultural infrastructures, Kochi had to respond from an informal and fragile context. Many of the spaces we worked with were dilapidated, historically layered, and socially active. From the beginning, it was important that the Biennale sent a clear message to the state and the public—that contemporary art could play a critical role in building cultural infrastructure, shaping new pedagogies, and educating younger generations.

Programs such as the Students’ Biennale, Children’s Biennale, Artists’ Cinema, and the Pepper House Residency were conceived as parallel knowledge platforms rather than side projects. They aimed to expand access, create new syllabi for art-making, and invite diverse publics into sustained engagement with contemporary art. One of our earliest interventions was advocating for the use of the Muziris Heritage Fund to restore and preserve culturally significant sites across Kerala—churches, mosques, temples, and spaces like Durbar Hall—underscoring a commitment to pluralism and shared heritage. As of today, we have KNMA showing one of the best academics – Gulam Mohammed Shaikh inside this very hall that was restored back in 2012.

The lessons from these undertakings have been enduring. They reaffirmed the need to continuously educate, to argue for better and permanent art infrastructure, and to imagine institutions not as fixed monuments but as evolving public resources. For me, this work remains an ongoing commitment—to provoke new infrastructural imaginations that allow art and knowledge to truly flourish.

Q. URU Art Harbour, which you founded in 2016 in Mattancherry, explicitly focuses on local culture, Kerala’s history of social action, maritime history, and human migration. How does this project differ philosophically and operationally from conventional commercial galleries or institutional frameworks?

Riyas Komu: URU Art Harbour emerged from a very specific moment of reflection after the early years of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale. When we began the Biennale, the central idea was to tell stories rooted in Kochi and Kerala—stories of coexistence, maritime histories, social action, and resistance. The Biennale’s original mission was explicit in its intent to speak beyond Euro-American art historical frameworks and to position art as a site of resistance rather than spectacle.

However, after 2014, the Biennale began to shift. As it grew in scale and visibility, it also became increasingly shaped by institutional expectations and external projections—often framed as a “people’s biennale,” but in ways that sometimes diluted its local specificity. That moment made it clear to me that there was a need for a more grounded, autonomous space—one that could remain accountable to local histories and communities without being overdetermined by institutional structures.

URU Art Harbour was founded in Mattancherry in response to this need. Philosophically, it operates from within the neighbourhood rather than above it. Operationally, it does not function as a commercial gallery or a conventional institution. URU supports research through grants, produces long-term artistic and archival projects, and works closely with communities—through collaborations with local groups, philosophers, artists, children, and researchers. It is a home-grown institution that allows time, care, and locality to shape artistic practice, making it less about representation and more about sustained engagement and shared knowledge production.

Q. The Aazhi Archives collective operates with the mission “Art+Knowledge+People,” explicitly positioning people as repositories, protagonists, and custodians of knowledge. How does this framework challenge conventional art historical narratives that often marginalize local voices and epistemologies?

Riyas Komu: I recall a remark made by K. G. Subramanyan during his visit to Kerala in 2014, when he said that art education must hold the history and collective memory of its location—the knowledge embedded in the everyday practices, materials, and visual cultures around it. That idea has stayed with me and directly informs the ethos of Aazhi Archives.

Aazhi operates by recognising location as both a grounding and an expansive force. Situated in Kerala, it acknowledges the specificity of place while remaining connected to a vast global network shaped by movement, exchange, and migration. By centering people as repositories and custodians of knowledge, Aazhi challenges conventional art historical narratives that often privilege written archives, elite institutions, and linear histories, marginalising local epistemologies in the process.

Our work engages with migratory narratives, the ocean as an archive, and floating histories that resist fixed borders and singular authorship. In this context, Art + Knowledge + People becomes an ongoing, open-ended journey—one where the ocean itself functions as an archive, holding memories that are dispersed, layered, and continually in motion.

Q. Sea—A Boiling Vessel emerged from interactions between historians and artists exploring Indian Ocean and Kerala histories. How did this collaborative methodology between academic research and artistic practice generate different kinds of knowledge or insights than might emerge from disciplinary silos?

Riyas Komu: Sea—A Boiling Vessel emerged from Aazhi Archives’ recognition of a critical vacuum between disciplinary silos—particularly between academic research and artistic practice. From the outset, we were interested in how knowledge shifts when historians, archaeologists, and artists work alongside one another rather than in parallel. As an institution, Aazhi deliberately positioned itself within this in-between space, allowing research to remain open-ended and responsive rather than conclusive.

This approach had earlier precedents in the first Kochi-Muziris Biennale, where several works were developed through engagements with historical knowledge and oceanic memory. For instance, Vivan

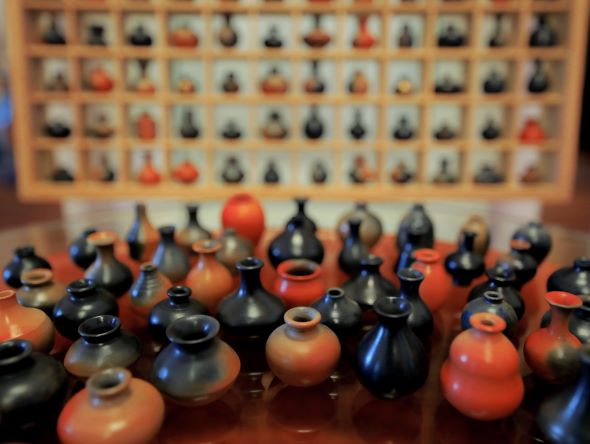

Sundaram’s work responded to pottery shards which were available at the Pattanam excavation site, that was loaned from Kerala Council of Historical Research to produce a work for the very initial editions of the Biennale. Work by Rigo 23—a Portuguese artist confronting colonial atrocities in Kochi—demonstrated how artistic practice could critically readdress inherited histories from within. It reasserts that biennale also started with excavation as metaphor.

In Sea—A Boiling Vessel, these possibilities were recalibrated further through engagements with archaeological sites and processes of excavation. Projects like Archaeo-logical Camera, developed in collaboration with Aazhi Archives, foregrounded excavation itself as a methodological and political act. Museum repositories, community-led initiatives, films on waterways and trade histories, and projects addressing migration and coexistence—particularly Kochi’s history as a site of Jewish settlement and relative peace—expanded the archive beyond texts and objects.

What emerged was a form of knowledge that was layered, embodied, and dialogic—produced through conversation, encounter, and translation—offering insights that disciplinary boundaries alone cannot generate.

Q. You’re launching Amphibian Aesthetics as the next edition of AA’s work, expanding from oceanic imagination to explore connections across geographies, aesthetics, and media. What prompted this conceptual evolution? How does the “amphibian” metaphor specifically address contemporary concerns about migration, ecology, and belonging?

Riyas Komu: Over the last decade, we have been closely engaging with Kochi as a landscape – cultural, social, political and environmental; and over this process we have realised the centrality of the oceanic in its historical and contemporary make up. Since 2016, along with scholars and thinkers, I have been involved in putting up exhibitions such as the ‘Mattancherry Project’, and the critically acclaimed ‘Sea A Boiling Vessel’ (Kashi Hallegua, 2022) which looks at the slave histories, maritime histories, migratory histories of Kerala. Through these engagements, the waters emerged as the key medium of civilisation in this region in contrast to the terrestrial movement of exchange in the northern parts of the peninsula. Such flows across the waters have also given rise to social and spatial fluidities which can still be seen in the landscape of Kerala.

The sea brought in waves of European colonialism; ideas and goods, religions and cultures were washed ashore and transported. All these transformed the cultural, political and spiritual economy of the region. Keralites migrated to all parts of the world. This encounter and exchanges between Kerala and Indian Ocean have encrusted, seeped in and sedimented in a variety of ways in the region’s soil and water, mind and intellect as much as its visions and apprehensions.

Given the geopolitical and environmental crisis we are facing globally that often cause involuntary movement of people from their places, we imagined the condition of the ‘amphibian’ that is able to inhabit the realities of two (or more) worlds throughout its existence. At its heart, the amphibian becomes a metaphor for adaptability and shared vulnerability—a figure capable of moving between land and water, past and future, material and immaterial conditions. The practices of artists chosen themselves represent multisited and multimodal forms of existence and approaches.

For example, The collective of CAAS (City as a Spaceship), whose members are spread across continents, works at the thresholds between Earth and space, using remote and extreme environments as laboratories for reimagining how humans might live in the future. They see Earth and outer space as part of a single continuum and envision modular, self-sufficient “micro-ecosystems” that can also connect with others when beneficial. Rami Farook, based in UAE, brings to us ways in

which spaces of worship in Kerala remain a vessel of memory, resilience, and continual renewal amidst a site of construction and collapse. Kerala based Ratheesh T’s work speaks of solidarities between people that sustain human relations beyond caste and religion, studied through the crucible of Kochi.

Q. AA explicitly resists “conventional event-formats and institutional immobilities” in the art/educational field. What specific institutional fatigue, ideological and aesthetic, were you responding to? How do your proposed “hybrid modes of academic courses” (combining offline/online, institutional/informal) practically subvert these structures?

Riyas Komu: Aazhi Archives attempts to recalibrate what Kochi promised as a cultural initiative in 2012. In some ways, the Biennale functioned more as a seasonal condition—an open temporal framework that allowed experimentation, hybridity, and even precarity. This imagination deeply informed Aazhi Archives. We carry forward that impulse by thinking of institutions not as static structures but as evolving platforms that can continually reimagine futures for arts management, curation, and pedagogy.

A key example of this was the Students’ Biennale, that I conceptualised as the Director of Programmes at the Foundation, where the site of making became the site of learning. Students engaged directly with artists through workshop-based models, encountering “making as thinking” rather than absorbing art history as a closed narrative. This format disrupted institutional fatigue around how art is taught and continues to be a model I strongly believe in. Similarly, the Children’s Biennale expanded access by foregrounding curiosity, play, and experimentation over instruction. I must commend the Foundation for keeping the Students’ biennial alive.

Aazhi Archives extends these possibilities further through hybrid academic modes—combining online and offline engagement, institutional and informal learning—to subvert rigid hierarchies of knowledge and create porous, responsive spaces where learning remains active, embodied, and shared.

Q. The Ishara House project, with Amphibian Aesthetics running through March 2026, brings together artists and collectives from South Asia, the Gulf, and beyond. How are you navigating different art historical canons, curatorial priorities, and institutional contexts across these regions? What are the tensions you’re navigating?

Riyas Komu: The Ishara House project represents one of the most significant recent developments in Kochi’s cultural landscape, particularly because it extends and deepens conversations that many of us have been building through earlier projects around migration, labour, and transregional exchange—such as Migrant Dreams and Dubai Elsewhere. Ishara House opens up a new curatorial imagination by activating long-standing cultural, historical, and economic ties between South Asia, the Gulf, and the Indian Ocean world.

Navigating these regions means working across multiple art historical canons, institutional expectations, and curatorial priorities that do not always align. South Asian art histories often remain tethered to postcolonial frameworks, while Gulf institutions operate within different temporalities, patronage structures, and narratives of modernity. Amphibian Aesthetics responds to these differences by refusing a singular canon and instead foregrounding fluidity, overlap, and transition—allowing practices to move between geographies, disciplines, and histories without being fixed within one institutional logic.

The tensions we navigate are productive rather than obstructive: between local specificity and transregional circulation, between institutional frameworks and artist-led experimentation, and between historical memory and speculative futures. That Ishara House has been committed to supporting South Asian art practice for over six years makes it a crucial interlocutor in this process. We are deeply grateful to Smita Prabhakar and the Ishara Art Foundation for enabling Amphibian Aesthetics to function not just as an exhibition, but as a long-term, transformative curatorial proposition running through 2026.

Q. How do you see the relationship between art institutions (museums, galleries, biennales) and grassroots or community-based art practices? Is there potential for productive transformation of institutional structures from within, or does genuine counter-institutional practice require remaining exterior to these frameworks?

Riyas Komu: I see the relationship between art institutions and grassroots or community-based practices as one of proximity rather than opposition. Working in Kochi gives us a particular advantage: the presence of the Biennale has created an expanded cultural ecosystem where institutions, independent spaces, and community initiatives can meaningfully intersect. This has allowed us to test how institutional structures can be productively stretched from within, rather than simply resisted from the outside.

Through our exhibitions and long-term projects, we have been able to build collaborations across different scales of institutions. Museums such as the Pazhassi Raja Archaeological Museum have loaned historical objects for the exhibition Archaeo Logical Camera, while the Muziris Heritage Project supported the BoatCast project for Amphibian Aesthetics. The Kerala State Archaeological Department has enabled access to archives, sites, and material histories that would otherwise remain closed. These collaborations demonstrate how institutional resources can be activated in ways that are responsive to contemporary artistic and community-based inquiry.

At the same time, partnerships with international platforms like Alserkal and Galleria Continua, alongside local spaces such as Kashi Art Café, have helped create a porous institutional network—one that moves between formal and informal modes of working. Transformation happens through sustained negotiation, trust-building, and the willingness to reframe institutional authority so that it can support, rather than contain, grassroots and community-led artistic practices.

Q. Throughout your career, from Venice Biennale participation to representing Iran’s pavilion to your recent work with AA, your positioning within and outside institutional frameworks has been strategic and deliberate. How do you reflect on your own complicity within systems you simultaneously critique? What responsibilities does a politically engaged artist-curator carry in this regard?

Riyas Komu: My positioning within and outside institutional frameworks has always been conscious rather than accidental. Whether participating in the Venice Biennale, representing the Iranian Pavilion, or working through Aazhi Archives, I have approached institutions not as neutral platforms but as complex sites shaped by power, ideology, and contradiction. The Iranian Pavilion, for instance, was not an isolated gesture—it extended a solo project I developed at Azad Gallery in Tehran titled Safe to Life, which addressed internal conflicts and the fundamental role of religion as a persistent site of tension rather than cohesion.

I have never operated as a single-project artist. My practice unfolds across long durations, between geographies, and bureaucratic structures which inevitably involves navigating multiple layers of administration, regulation, and complexity. Rather than viewing this as complicity to be avoided, I see these moments of friction as sites of engagement—opportunities to articulate one’s position with greater precision and to unsettle the comfort or “peace” that institutions often seek to maintain.

I do not believe in rigid binaries of being either inside or outside the system. Nor do I operate with double standards. The responsibility of a politically engaged artist-curator today—particularly in the Indian context—is to negotiate these in-between spaces with clarity, accountability, and self-reflection. It is a complex position, but one that allows critique to function not from a distance, but from within the very structures it seeks to question and transform.

Q. Your work consistently amplifies South Asian and postcolonial perspectives. How do you prevent these frameworks from becoming aestheticized or depoliticized? What does it mean to maintain critical urgency in institutional contexts that often absorb and neutralize radical gestures?

Riyas Komu: My attempt to foreground South Asian and postcolonial perspectives is always anchored in sustained scholarship rather than surface aesthetics. One of the ways I try to prevent these frameworks from becoming aestheticized or depoliticized is by embedding artistic practice within long-term research conversations. Amphibian Aesthetics is not a standalone exhibition but the culmination of multiple scholarly trajectories coming together over time.

The project draws on contributions from thinkers across disciplines—Dr. C. S. Venkiteswaran from cinema studies, Prof. M H Ilias as a scholar of Islamic history and Director of Gandhian Studies, and Amrith Lal as a senior political journalist and commentator, among others. Their engagements ensure that the exhibition remains rooted in historical complexity, political analysis, and ethical debate rather than visual shorthand or identity-based representation.

Maintaining critical urgency within institutional contexts requires constant recalibration. Institutions have a tendency to absorb radical gestures and render them inert, often through spectacle or scale. To counter this, I insist on processes that foreground dialogue, disagreement, and context—where exhibitions function as sites of thinking rather than endpoints. In that sense, Amphibian Aesthetics extends and reactivates the critical discussions that were first initiated during the early years of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale in 2010, keeping those questions alive rather than resolved.

Q. With Amphibian Aesthetics launching in December 2025, what are your priorities for this inaugural exhibition at Ishara House? How are you positioning this within the broader contemporary art landscape?

Riyas Komu: The exhibition adapts a two-fold curatorial approach in its selection of artists while considering the work of art and the artist within the broader context of the Anthropocene. Firstly, it brings the viewers to closely consider the vulnerable state of our current times, to consider precarity closely and familiarise with the physical and social aspects of migratory experience. On the other hand, it brings the experiences of migratory cultures of the past in order to possibly mediate or mitigate the conditions of the contemporary.

Contemporary art can play a vital role in widening ecological conversations, particularly when it reorients us toward forms of collaborative living. Amphibian Aesthetics proposes precisely such a shift: a manifesto that urges us to “move on” by imagining coexistence across species, elements, and knowledge systems. Water, in this exhibition, is not merely a theme but a carrier of cultures, memories, and movements. It reminds us of peace, memorialises intellect and genius, archives conflict and war, and argues—both gently and firmly—against violence. The very site of the exhibition functions as evidence of possible futures built on coexistence.

The ecological crisis we face demands not just new policies but new imaginaries. To think ecologically today requires rhizomic, entangled modes of thought. This is where the amphibian becomes a powerful metaphor. To be amphibious is to inhabit land and sea, past and present, human and more-than-human; to understand life as a field of forces and entangled relations. Contemporary art, by cultivating such amphibious sensibilities, can sharpen public awareness and subtly steer policy by reframing how we perceive resilience, interdependence, and survival—whether through mushrooms flourishing in nuclear ruins or frogs navigating shifting ecologies. Through these gestures, art becomes both witness and guide in an era of planetary disruption.

Q. The concept of “amphibian aesthetics” suggests liminality, adaptation, and existing between worlds. In the context of current geopolitical instability, climate crisis, and human displacement, what does amphibian thinking offer that traditional art historical frameworks cannot?

Riyas Komu: The idea of the amphibian emerged from our long academic and aesthetic engagement with maritime imagination. Many of our earlier shows and academic programmes were around the themes of maritime trade, exchanges, migration, displacement, slavery etc, all of which were in one way or other connected with the sea and travels across it. It was an attempt to reverse the gaze and shift positions, to start looking at the land from the fluid, shifting point of view of the sea, to use sea not as a metaphor but a metaphor, a whole new way of looking at life and the world, cultures and livelihoods, beliefs and rituals. The idea of the amphibian is something that takes the idea forward, one that goes beyond such binaries, and looks at the world and life, economy and culture, systems and beliefs as nodal points where many journeys intersect, diverse elements come together.

Firstly, binaries have become redundant at all levels, social, political, economic and philosophical; even in terms of the idea of the human. In the post-human, post-truth world we live in, we can’t afford to think and act in/with such binary concepts. Everything is mixed up, all boundaries are transgressed, and all hitherto solid systems are facing a meltdown. For instance, capital is freed from national boundaries and currencies; it has become mobile and fluid, and has changed into more abstract forms, while labour whose surplus produces it remains geographically scattered, internally fragmented and as a class, informalised. Covid pandemic was a biological moment when we realised humans are just one species among many, even as a single continuum of bodies on earth, contiguous and porous with the virus traversing through it seamlessly, and also through a viral network that links it with other species. Ecological issues and conflicts too can no longer be divided as local and global, or between the North and South, as the common destiny we share has now brought us face to face with the real possibility of extinction. Global politics too has outgrown its old binaries, like Communist/Capitalist, Democratic/Autocratic and so on; no either/or this/that categories work anymore. While digital media democratises information exchange it also provides State and Capital with monstrous powers of surveillance and control. So on and so forth in every area of life, polity, economy, ecology…

So any imagination, political or aesthetic, needs to take this chaos – very structured at one end, and disastrously polymorphous at the other – into serious and urgent account. This is what prompts and provokes us to think about amphibian modes of understanding and expression, one that traverses across boundaries and binaries.

Q. For your readers and the broader art community in India, what’s one misconception about your work or curatorial practice that you’d like to address directly? What aspect of your work remains most misunderstood?

Riyas Komu: There is a tendency to see my curatorial and institutional roles as separate from—or even opposed to—my identity as an artist. Living what I often describe as an amphibious life, moving between artistic practice and curatorial or institutional responsibilities, inevitably creates a sense of dichotomy. From the outside, this sometimes leads to the assumption that I have become primarily an administrator rather than a practitioner.

What often gets misunderstood is that my curatorial work is itself an extension of my artistic practice. Since around 2006, the artworks I have produced have absorbed and reflected the same questions that shape my curatorial thinking—about constitutional values, resistance to religious majoritarianism, migration, and the negotiation of multiple knowledge systems. The shift is not one of abandonment, but of recalibration.

My practice involves wading through institutional collaborations, working with individuals and communities, negotiating timelines, sites, and production realities. Reflection, for me, is not separate from action; it is embedded within it. The loss I sometimes feel as an artist is real, but so is the conviction that this hybrid position allows me to think, make, and intervene in ways that would not be possible from a single, fixed role.

Cover Image Credit: Anuj Daga

Athmaja Biju is the Editor at Abir Pothi. She is a Translator and Writer working on Visual Culture.