India’s beautiful tricolor flag, with its saffron, white, and green stripes and the navy blue Ashoka Chakra has an incredible 43-year journey behind it. It’s a symbol that went through revolutionary struggles, community negotiations, and democratic decisions to become what it is today. The flag’s journey from 1904 to 1947 shows us how symbols of protest can become symbols of government, and how every design choice reflected deep conversations about what it means to be Indian.

How it all began?

The story starts in 1904 with an unexpected person—an Irish woman named Sister Nivedita, who was a follower of Swami Vivekananda. At Bodh Gaya, surrounded by famous Indian intellectuals like Rabindranath Tagore, she designed India’s first organized attempt at a national flag. Her red square cloth had a yellow thunderbolt symbol and “Vande Mataram” written in Bengali, surrounded by 108 oil lamps.

But the real turning point came in 1906 during protests against the Partition of Bengal. On August 7, 1906, the Calcutta Flag made its dramatic appearance—a horizontal tricolor with white lotuses on green, “Vande Mataram” on yellow, and symbols uniting Hindus and Muslims on red. Created by Sachindra Prasad Bose and Sukumar Mitra, this flag was raised at Parsee Bagan Square during massive protests, marking when flags became weapons of resistance.

The revolutionary spirit went international when Madame Bhikaji Cama unfurled the Berlin Committee Flag at an international meeting in Stuttgart on August 22, 1907—making it the first Indian flag displayed on foreign soil. This version had seven white stars, “Vande Mataram” in Hindi, and symbols bringing Hindu and Muslim communities together. Cama’s powerful words echoed across continents: “Behold, the flag of independent India is born!”

Gandhi’s Role

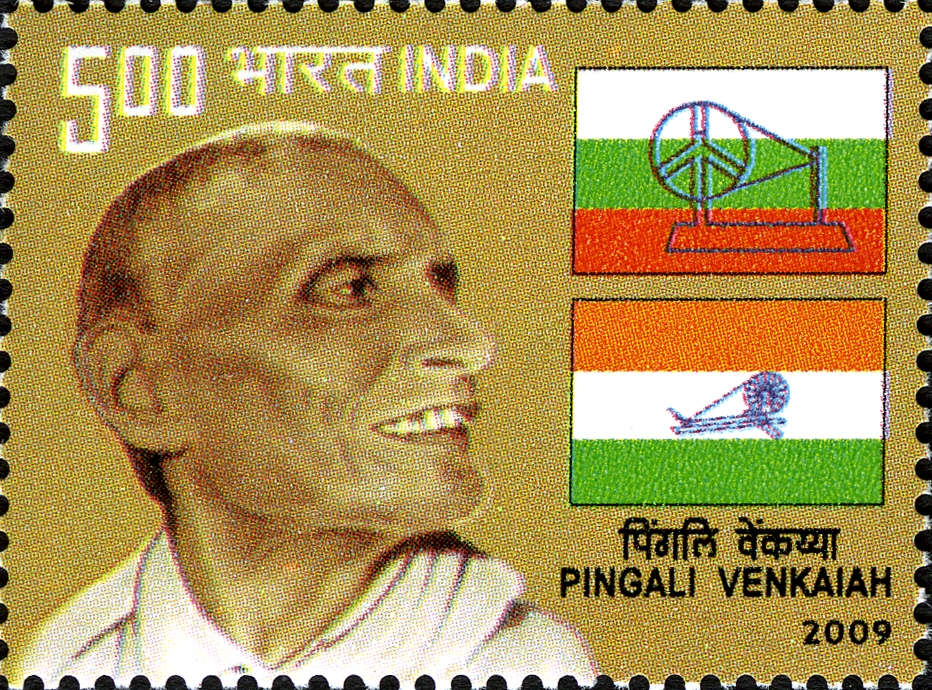

The flag movement reached its game-changing moment in 1921 when Mahatma Gandhi asked Pingali Venkayya, a brilliant scholar known as “Diamond Venkayya” for his work in geology, to create a flag that could unite all Indians. Venkayya’s first design had two horizontal bands—red for Hindus and green for Muslims—with a spinning wheel in the center.

stamp by India Post, Government of India

Gandhi added the white stripe. The spinning wheel (charkha) became the heart of this vision, symbolizing self-reliance, the dignity of work, and economic independence from British rule.

By 1929, Gandhi had given the flag completely new, secular meanings: saffron meant courage and sacrifice, white represented truth and peace, and green showed faith and prosperity. In 1931, the Congress party made this official, replacing red with saffron to move even further away from religious interpretations. This Congress tricolor became India’s unofficial national flag, carried through famous movements like the Salt March and Quit India Movement.

Turning a political party’s flag into the nation’s flag required incredible care and sensitivity. When the Flag Committee was formed on June 23, 1947, led by Dr. Rajendra Prasad, they had to create a flag “acceptable to all parties and communities.” The committee included important leaders like Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Sarojini Naidu, C. Rajagopalachari, K.M. Munshi, and B.R. Ambedkar—people representing India’s incredible diversity.

The key suggestion came from Badruddin Faiz Tyabji and his wife Surayya Tyabji, who proposed replacing Gandhi’s beloved spinning wheel with the Ashoka Chakra (wheel). Badruddin convinced Gandhi that Emperor Ashoka was respected by both Hindus and Muslims, while the dharma wheel represented universal law rather than party politics. Surayya, a talented artist, actually created the sample flag design, first painting the chakra black before changing it to navy blue when Gandhi objected.

On July 22, 1947, India’s Constituent Assembly unanimously adopted the tricolor. Nehru praised its practical symmetrical appearance, while Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan explained how the chakra represented dharma and good governance. The very first official flag, hand-made by Surayya Tyabji herself, was hoisted on Nehru’s car during independence celebrations.

India’s flag specifications demonstrate remarkable attention to technical detail reflecting cultural values. The 3:2 aspect ratio creates perfect proportional harmony, while the three equal horizontal bands maintain visual balance. The Bureau of Indian Standards specifies exact color coordinates: India saffron (#FF671F), white (#FFFFFF), India green (#046A38), and navy blue (#06038D) for the Ashoka Chakra.

The original requirement for hand-spun khadi cloth embedded Gandhi’s economic philosophy directly into the flag’s material composition. Thread count was specified at exactly 150 threads per square centimeter, with one square foot weighing precisely 205 grams. This requirement, maintained until 2021, ensured that every flag physically embodied the principle of swadeshi (self-reliance).

The Flag Code of India (2002) governs display protocols with extraordinary precision: flags fly from sunrise to sunset (night display permitted if illuminated), must never touch ground or water, cannot be used as clothing below the waist, and should be handled with ceremonial dignity. The code’s 2002 amendment, following the landmark Naveen Jindal Supreme Court case, expanded citizens’ rights to display the flag daily rather than only on national holidays.

The Indian tricolor’s 43-year evolution from Sister Nivedita’s spiritual vision to today’s constitutional symbol reveals how national identity emerges through democratic negotiation rather than imposition. Each design iteration—from the 1906 Calcutta flag’s anti-partition resistance to Gandhi’s 1931 charkha flag embodying self-reliance to the 1947 Ashoka Chakra representing universal dharma—responded to changing political circumstances while maintaining continuity in the horizontal tricolor format.

The flag’s greatest achievement lies not in its final design but in the process of its creation—demonstrating how diverse communities can forge shared symbols through patient dialogue and mutual accommodation. The transformation from communal colors to secular meanings, from party emblem to national symbol, from resistance flag to governance symbol illustrates democracy’s capacity for inclusive symbol-making.

Contributor