Gallery Dotwalk’s move to a new, strategically located location in Defence Colony, New Delhi, represents a major institutional transformation; it symbolises a conscious broadening of the gallery’s connection with India’s art capital’s thriving art environment. By establishing itself within this historic cultural hub, Dotwalk aspires to foster a more intimate accessibility between current practice and the rich art audience in the capital city.

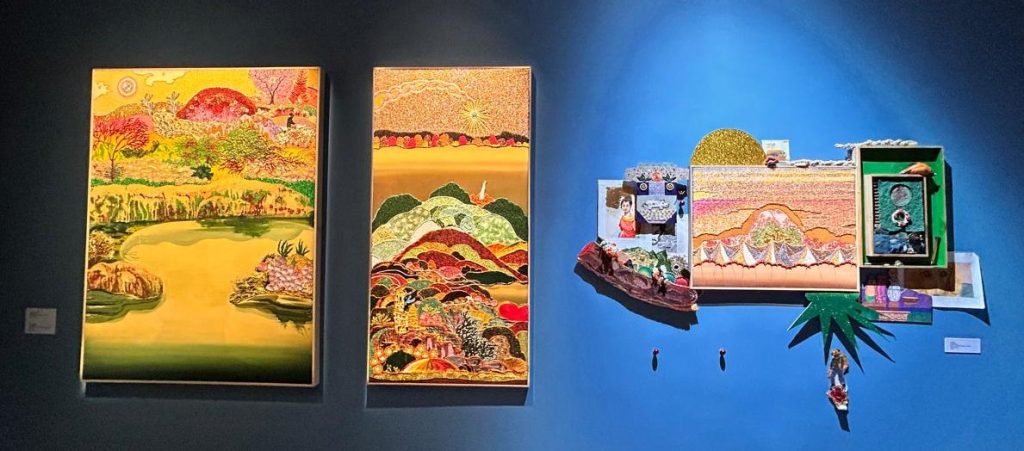

The gallery’s Drifting Through the Quiet Veins exhibition, which disrupts the conventional “white cube” experience by turning the gallery into a multisensory space, marks the start of this new phase.

The first show uses an immersion rather than a static display. The title itself alludes to an underground or circulatory investigation—a passage through the neglected or inner rhythms of life. By synthesising acoustic atmospheres, video displays, the show creates a “sensory landscape” that enables viewers to experience art as an embodied experience rather than a visible object.

Ravinder Reddy and Chandrashekar Koteshwar’s artworks negotiate the line between form and psychological resonance, giving the works an imaginary foundation. The show explores the nature of memory and the transient moment through the “fragments” provided by artists such as Abdulla PA, Mehak Garg, and Priyaranjan Purkait. Using their different media to map the “quiet veins” of the modern human condition, Amjum Rizve, Sudhayadas S, and Sujith SN expand the investigation into the domains of space and atmosphere.

As a curatorial intervention, Drifting Through the Quiet Veins is a natural fit for Dotwalk’s new aim. By emphasising “sonic atmospheres” and “video immersives,” the gallery shows its dedication to experiential art and post-media practices, and it is a significant addition to the city’s conversation, providing a place where the bustle of the metropolis meets a deep, reflective quiet.

Within the silence of the exhibition room, light and sound play a visceral role, operating less as environmental variables and more as material residue. Here, eight artists have painstakingly created a delicate map of the underground, untold—an investigation of the unseen forces and stories that persist below the surface of what we see. Instead of being immobile monuments, the pieces in this show inhabit a liminal space that invites the viewer to traverse a terrain of tidal recollections, respiratory colours, and the murmurs of items rescued from the edge of existence of our muted life.

The exhibition area changes, becoming a metabolic network—a network of veins that carry the labour of the Sundarbans in a slow, regular pulse. By connecting the massive ecological scale of the wetlands with the subtle acoustics of domesticity, this carefully designed space blurs the boundaries between the intimate and the geographical. The gallery appears as a living system, circulating the ghostly energy of stories that have traditionally been ignored or repressed by bringing divergent modalities of existence into a single spatial conversation.

Ultimately, the show serves as an ontological study of the lives of the “discarded.” The artists conduct a forensic excavation of memory through a wide range of media, giving the forgotten and the ghostly a bright presence. Whether through the abstract memory of a net or the breath of a pigment, the collection of what is “lost” is never truly gone out of our memory. It is merely waiting for a moment of stillness to recapture its essence, as in the one provided here, beyond our ability to resurface and articulate its enduring significance within our contemporary consciousness.

Abdulla PA creates a “chamber of shadows” in his piece, serving as a powerful spatial metaphor for the unpredictability of assurance. His installation traps the viewer in a maze of visual echoes by manipulating light and surface to create a backdrop in which ”reflections” raise a series of unanswered queries. This intervention not only casts shadows but also creates a void in which the boundaries between the actual object and its ghostly duplicate collapse. More requires a confrontation with the elusive nature of truth and the persistent ambiguity of the seen.

Meha Garg charts what she calls the “emotional architecture”, examining the transitional area where domesticity and the psyche collide. Garg treats the home as a memory space for the unsaid through a subtle interplay of audio traces of “looted” or “muted” female conversations. These sounds are more than just fleeting; they transform into atmospheric residue. Invisible stories that quietly saturate the walls like dust, turning the space into a living body, and reverberating with the memory of common female experience.

Anjum Rizve presents an alchemical table of artistic production, drawing the observer into a realm of material metamorphosis. Rizve repurposes threads and colours as magical conduits into unseen places, elevating them beyond their tactile utility through this staged site of creation. By manipulating the raw materials of his medium, he maps mental and geographical landscapes on the edge of ordinary perception, making the abstract both palpable and navigable. This argues that the process of creation is a form of cartography.

Priyaranjan Purkait practices acts at the nexus of tactile materiality and ecological memory, employing knotted fibre to express the unstable terrain of the Sundarbans. In his work, the net is stripped of its utilitarian role and repurposed as a cartography instrument—a web that captures not fish, but the ethereal tensions of a delta in motion. Purkait creates a tactile, eerily transparent geometry by suspending these complex structures, establishing a physical dialogue with the “withheld” and transforming the invisible currents of environmental labour and the receding topographies of the marshes.

To ground the exhibition’s intangible aura, the works of Sujith, Chandrashekar Koteshwar, Sudhayadas, and Ravinder Reddy give a key material and ontological anchorage. Their combined efforts act as a stabilising influence in the “drift,” expressing a deep conversation between the performative and the elemental. The exhibition unites the earthly and the human through Koteshwar’s investigation of the body’s limitless dynamic potential and Sujith’s interaction with the earth’s fragmented memory. Reddy’s towering look, which depicts the sky’s constant negotiation with the horizon, and Sudhayadas’s mastery of terracotta’s archaic syntax, which gives life to primal forms, further enhance this. Together, these artists transform the gallery into a space of rigorous elemental investigation, where the ancient and the present converge.

The curatorial statement for this exhibition is a beautiful and valuable piece of writing. Instead of using dry, academic language, it uses a poetic tone to help the audience understand how they should behave and feel within the space. The phrase “ecology of attention” is highlighted in the curatorial note. It tells the viewer that the exhibition isn’t just a list of things to look at; it is an environment where how you look is just as important as what you see.

By inviting the body and the ear to become instruments for experiencing art, the curator reminds us that art is not merely visual but an ambience. It invites us to listen and take in the room’s ambience. The advice to “unlearn the hurried gaze” is the most potent element. We typically take a look at things and move on in our frenzied setting. This phrase invites the viewer to slow down and exercise patience. The final sentence, about carrying away the “weight of having been present”, is quite poignant. It means that the exhibition will leave a lasting emotional imprint on the spectator, rather than just a remembrance of an image.

Contributor