Gulammohammed Sheikh for Abir Pothi, Part Two

The ongoing retrospective of Gulammohammed Sheikh at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in New Delhi, on view through June 30, is as exhaustive as a retrospective should be. It gives an expansive view of the long, continuing career of this veteran artist, who enjoys a seminal position in the post-Independence modern Indian art.

The sheer number of works on display—about 190—selected from different genres and different periods by the museum’s chief curator and director, Roobina Karode, presents the evolutionary story of the artist’s work in a capsule. The selection shows the influences, the concerns and even the social issues that affected the artist at a particular period in time, and found their way in his art.

What, however, is the most striking aspect of this pictorial journey of Sheikh’s career is his constant engagement with Kabir, inarguably India’s most well-known devotional poet, who lived in the 15th century and whose verses (dohas) continue to exert influence till this day.

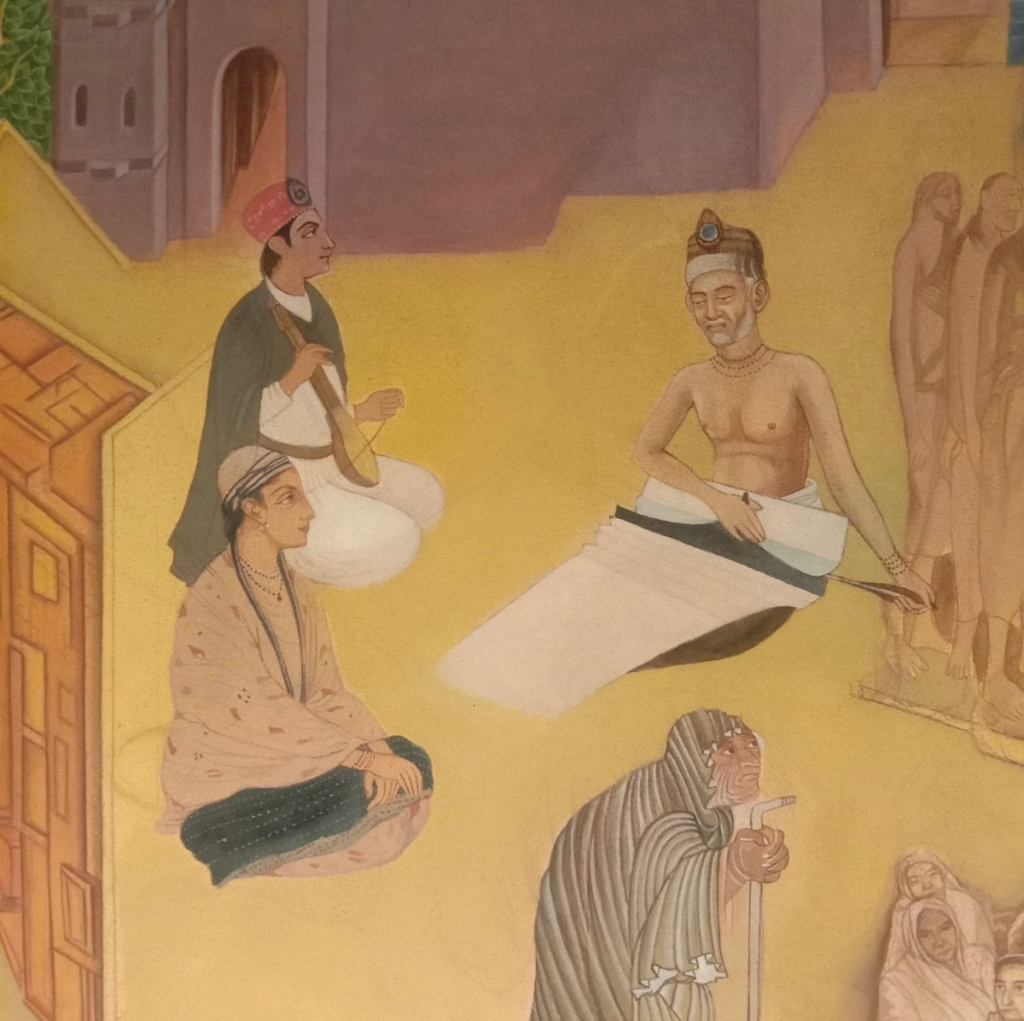

Kabir appears as a saintly, serene figure in many of Sheikh’s canvases—from the biggest one at the retrospective, ‘Kaarawaan’, 2019-2023, to the smaller ones tucked in far corners of the exhibition space, always as a weaver, the profession that he followed in Benaras, and identifiable with a band on his forehead, topped by a peacock feather.

According to Sheikh, even though the figure of Kabir started appearing as an element in his paintings earlier, it was only in the 1990s that he seriously engaged with it. He says in an interview with Abir Pothi, “The paintings on Kabir come at a late stage. The 1990s was a period of great turbulence. A lot of things happened during that time, such as the demolition of the Babri Masjid, the subsequent riots, and even the nuclear tests [conducted at Pokhran, Rajasthan, 11-13 May 1998 by the Atal Behari Vajpeyi government].”

Explaining further, he adds, “I’m not saying these are the only reasons. At that time, one felt there was a need for somebody to give a healing touch as there were so many victims around us. The turbulence that took place all around at that time made me look for something that I could incorporate in my work, as a soothing presence. I found Gandhiji to be one of those figures and made him a part of some of my paintings. A little later, I thought to myself, why not try Kabir?”

The experiment seems to have worked for him as the figure of Kabir, subsequently, found a place in several of Sheikh’s canvases, even though he moved on from one predominant theme to the other in his later years.

As a slight aside, it is important to note that while Sheikh has painted Kabir at work on a small loom, his face very clear, Mahatma Gandhi is shown walking away, a receding figure wrapped in loin cloth and shawl and walking away with the aid of a long walking stick. His back to the viewer, when contrasted with the front view of Kabir that Sheikh provides his audience, is worth pondering on.

Interesting in the context of Kabir is an undated oil on canvas from the KNMA collection, titled Kabir Ke Liye Commando (Commandos for Kabir). A heavily detailed work in the colour palette and his personal style of the 1990s, it shows a looming figure of Kabir sitting in the centre of a picture frame that seems to be a jungle vista. Through the thick vegetation appear two unmistakable figures of commandos, one on either side of Kabir. The commandos in camos wield guns and seem to disrupt the busy landscape of foliage in the background. But their relevance—in guarding Kabir—becomes apparent when the eye moves to the bottom of the canvas where crowds of people can be seen running helter-skelter, away from a possible mayhem, or a riot, perhaps. The work is fractious, not just when compared to others depicting Kabir in some form, but also when juxtaposed with the symbolism of Kabir.

In light of what the artist shares above, this painting seems to be skimming the nadir of his distress over the events of the 1990s.

He shares, “I had known about Kabir as a prominent historical figure since my childhood, and was aware of his importance. In school, when I used to study Kabir in Hindi, I became aware of his poetry, doha, sakhi, etc. In later years, I used to listen to Kumar Gandharva a lot, who is known for revolutionizing the musical interpretation of Nirguna Bhakti poetry, especially that of Kabir. Nirguna is very sparse, what you call non-ornamental. So, anyway, I had read it all, and thought to myself—if Kumar Gandharva can sing Kabir, why can’t I make Kabir? It might have seemed illustrative but I didn’t care, since much of our art from the pre-modern period was sort of both narrative as well as illustrative. The illustrations for the Ramayana, Mahabharat, historical accounts, the series of paintings on Bhakti ras, all of this from that period used some form of Nirguna poetry to drive home the point.”

What does he think about the every-increasing importance of Kabir in contemporary times?

“In our time? Oh! Kabir is still in our lives and will remain so. The reasons are not far to seek. His dohas, which can be understood as proverbs, such as—Bada hua to kya hua, jaise ped khajur, panthi ko chhaya nahi, phal lage ati door [In non-literal translation, it means: No point in becoming big like a date palm tree because it fails to provide shade and its fruit too hangs way up, out of reach] find an instant connect. There are so many others. His ulatbansi idiom (upside-down or twilight verse) is particularly interesting. The imagery is upside down. For example, Ek achambha dekha re bhai, thada singh charai gai, pehle bhayo poot, peechhe bhai mai, chela ke guru lagey pai [non-literal translation: I have seen great wonders, such as a lion tending a cow, a son taking birth before the mother, and the Guru touching the feet of his student]. There are many other such examples. That imagery lends itself to expression in music as Kumar Gandharva showed, and to visual arts as well. I too tried to experiment with the layers of Kabir’s poetry.”

Armed with Sheikh’s explanation on his engagement with Kabir, a second walkthrough of the exhibition reveals different interpretations of the paintings, especially when one frequently starts spotting the weaver with a peacock feather headband sitting stoically at work.

Featuring Image Courtesy: India Art Fair

Archana Khare-Ghose is a senior arts journalist, and a commentator on art, market, books, society and more