By Iftikar Ahmed

At Bikaner House, New Delhi, Sudip Roy’s ongoing exhibition Junjaali, on view until 20 December 2025, unfolds as a quiet yet deeply affecting return. The exhibition is not framed as a retrospective, nor does it attempt to compress decades of practice into a summarising gesture. Instead, it brings together works created over the last two years, most of them produced in Baharampore, Murshidabad, the region from which Roy originally comes. What emerges is not a look backward in the conventional sense, but a slow and deliberate movement through memory, place, and artistic evolution.

Roy has been based in Delhi for more than three decades. Yet Junjaali makes it evident that geographical distance has not diluted his relationship with Murshidabad. If anything, time and displacement have sharpened it. The exhibition reflects an artist who has travelled far, across cities and styles, only to feel an increasing pull toward the landscapes, people, and sensations of childhood. This return is neither sentimental nor indulgent. It is marked by fragility, by a sense that memory itself is something precious and perishable.

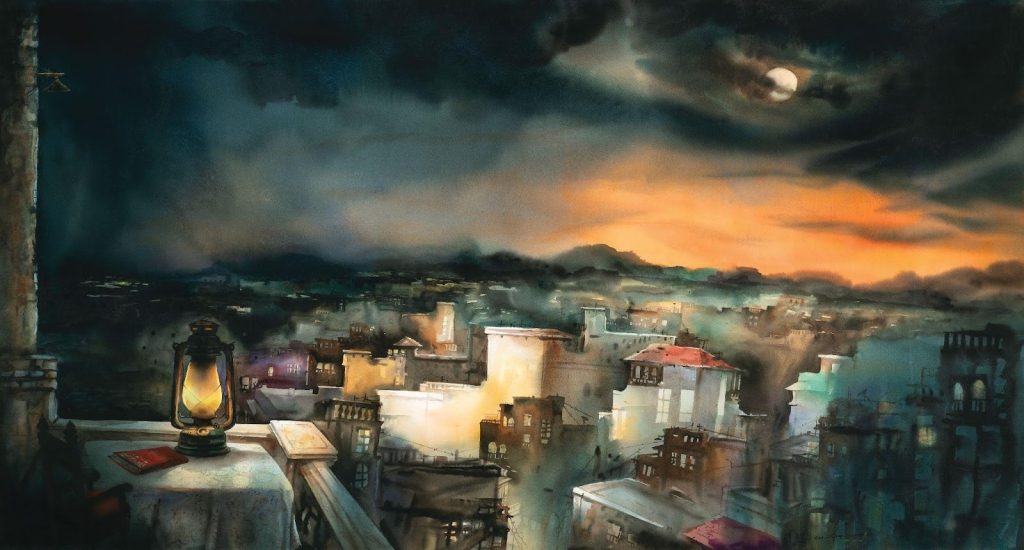

Sudip Roy was born in a village called Khandua in Murshidabad. Much of the village no longer exists today, gradually erased by the Padma river. When Roy speaks of his childhood there, he does so through sensory fragments rather than narrative nostalgia. He recalls nights illuminated by full moonlight that felt almost like day, and moonless nights where stars were so visible they could be counted. There was no electricity then. These details matter because they establish a rhythm of life that has disappeared, not only from Khandua but from most contemporary experience. Roy himself notes that such nights no longer exist in cities.

His movement from Khandua to Baharampore, then to Kolkata, and eventually to Delhi mirrors a larger journey that runs through Junjaali. The exhibition is shaped as much by physical travel as by the internal journeys of memory and practice. As Roy grows older, the past does not return as simple recollection. It arrives with urgency, accompanied by the awareness that memory can fade, fracture, or disappear altogether.

People from Roy’s childhood resurface within this landscape of remembrance. Figures such as Bakkar Sir, a mathematics teacher blind in one eye, appear not just as anecdotes rather as emotional coordinates. These memories anchor the exhibition in lived experience, reminding the viewer that the past is populated by individuals whose presence continues to shape one’s inner world.

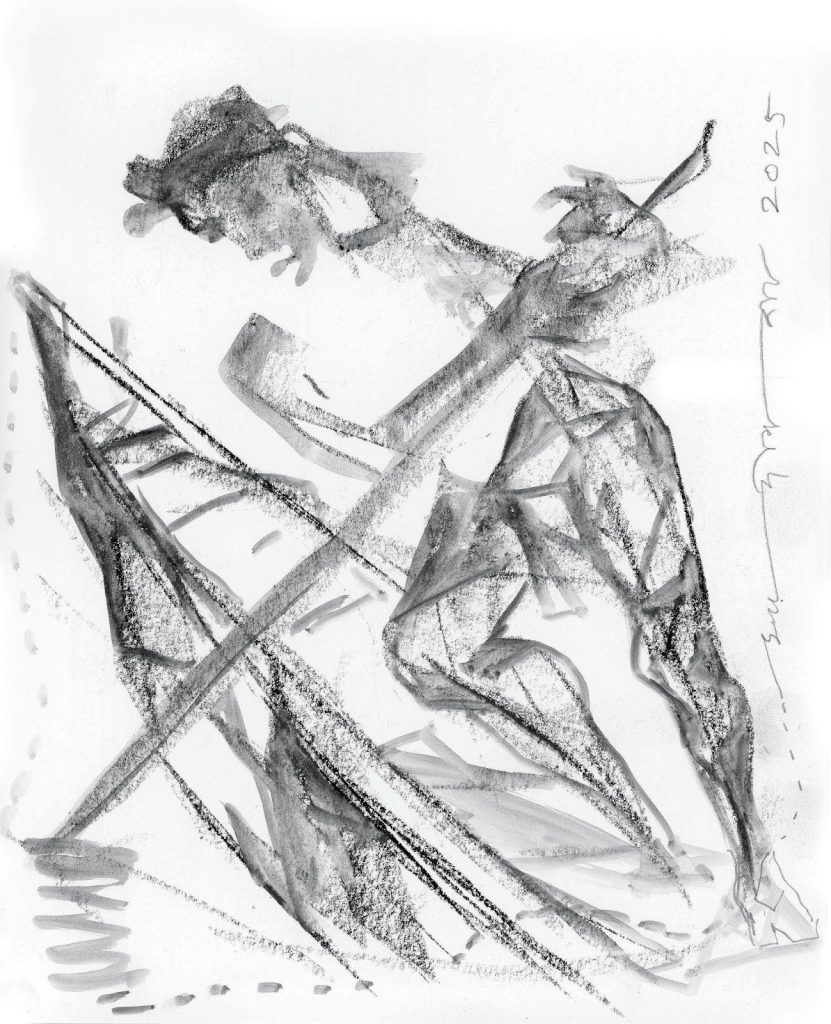

At the emotional core of the exhibition is the figure of Junjaali herself. Roy remembers her distinctly. She was twelve years old when he was nine. Untamed, restless, running through fields and wilderness. She caught ducks, pigeons, goats. Together they moved through a landscape that felt open and unbounded. Junjaali is a real person from Roy’s childhood, yet within the exhibition she becomes something more expansive.

The title Junjaali functions less as a descriptive label and more as a condition that frames the viewer’s encounter with the work. The word belongs to a fluid, spoken register rather than formal vocabulary. It suggests entanglement, inner knots, and restless confusion. It points toward emotional tangle, mental unease, and unresolved states of being. The title does not seek clarity or resolution as it performs conceptual labour.

In this exhibition, Junjaali functions as a state of being rather than a problem to be solved. It describes a psychological condition, a lived confusion that cannot be neatly untangled. The implication is subtle but powerful. Life, like memory, is knotted, and there is no clean exit. Some states must be lived inside rather than explained away.

This conceptual openness extends directly into Roy’s artistic practice. Over the course of his career, he has moved fluidly across styles and mediums, resisting the comfort of a fixed signature. He began as a realistic watercolourist, shifted toward semi abstraction, then abstraction, and has now returned to realism with renewed intent. Junjaali reflects this entire arc without presenting it as a narrative of progress or return.

Walking through the exhibition, one encounters a visual landscape that resists linear reading. Watercolours, graphite works, and bronze sculptures coexist without hierarchy. The works appear like fragments drawn from different emotional registers, held together by memory rather than chronology.

Roy’s realistic watercolours form a strong anchor within the exhibition. These works display his well-known command over light, atmosphere, and surface, yet they never slip into photographic exactness. Figures, landscapes, and interiors appear suspended in time, as if recalled rather than observed. There is a softness to their presence, a sense that the images are aware of their own fragility. The realism here is not performative. It does not seek to impress through technical virtuosity. Instead, it holds emotion gently, allowing memory to inhabit form.

The graphite works introduce a more introspective tempo. Often pared down and restrained, they feel closer to private notations than finished declarations. Lines hesitate, repeat, and sometimes dissolve, mirroring the uncertain movement of thought and recollection. These works carry a raw immediacy that contrasts with the compositional calm of the watercolours. They suggest moments where form is still searching for itself, where certainty remains provisional.

The bronze sculptures add another layer of presence to the exhibition. Solid and tactile, they bring weight and endurance into the space. Yet Roy consciously avoids monumentality here. The sculptures do not dominate the room or assert authority. Instead, they sit quietly, holding stillness rather than spectacle. Their material permanence exists in subtle tension with the exhibition’s recurring concerns with erosion, loss, and the passage of time.

This restraint becomes particularly striking when placed in dialogue with the monumental painting that anchors the exhibition. Spanning an entire wall at an imposing scale of fifty-two by twelve feet, the work is assembled in seven parts, creating a continuous yet segmented visual field. Unlike the sculptures, which withdraw from dominance, this painting embraces scale fully. Yet even here, monumentality does not translate into aggression or visual conquest. The painting envelops but does not overwhelm through force.

Composed of layered colours, shifting densities, and fractured surfaces, the work feels less like a single image and more like an emotional terrain. Its segmentation resists totality, suggesting that even at monumental scale, the experience remains incomplete and unstable. The painting mirrors the logic of Junjaali itself. Vast, immersive, and unsettled, it embodies entanglement rather than resolution. In contrast to the quiet endurance of the sculptures, this expansive work allows emotion to spread, bleed, and linger across space, turning monumentality into a site of vulnerability rather than control.

For Roy, abstraction functions emotionally rather than intellectually. He believes abstract art must evoke feeling in the viewer, much like music does. If something moves you, if it feels right, that feeling is sufficient. Explanation becomes secondary. These works do not demand interpretation but ask for response.

Together, these varied mediums form a continuum. The exhibition reflects an artist comfortable inhabiting multiple languages at once, much like memory itself, which never arrives as a single, stable image.

This emotional quality is central to understanding Roy’s work. His art is more emotional than cerebral. It does not announce theoretical positions or intellectual frameworks. Instead, it operates through mood, sensation, and remembrance. In a cultural moment saturated with spectacle and overstimulation, Junjaali offers a pause.

Art consultant and curator Swapnil Khullar, whose gallery is presenting Junjaali, captures this effect when she describes the exhibition and the artworks as a breath of fresh air and relaxing, especially in an overstimulated world. The remark is telling. Roy’s works do not compete for attention. They create space for stillness, inviting the viewer to slow down and linger.

Murshidabad itself remains a quiet yet powerful presence throughout the exhibition. Once the capital of the Nawabs of Bengal, Bihar, and Odisha, it is now marked by humility and historical layering rather than grandeur. Roy’s affection for the region is evident, yet it is never romanticised. The place appears as lived terrain, shaped by time, loss, and continuity.

Ultimately, Junjaali resists closure, allowing its knots to remain unresolved and affirming entanglement as a fundamental condition of living and creating. Memory is fragile. Nostalgia can ache. Artistic practice demands continual rediscovery. In moving forward, one often looks back.

Junjaali stands as a meditation on these conditions. It is an exhibition about returning without arriving, remembering without possessing, and creating without settling. The works do not attempt to untangle life’s knots. They stay with them. And in doing so, they offer something increasingly rare. A space to feel, quietly, in a world that rarely allows it.

Iftikar Ahmed is an art critic and writer based in India, writing on contemporary art and culture.

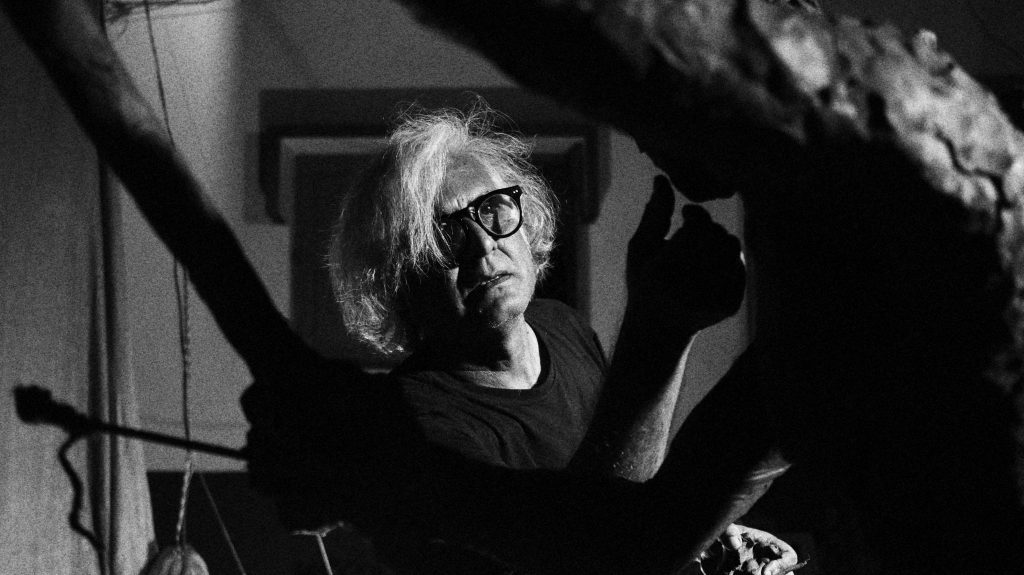

Cover Image: Sudip Roy is an Indian Contemporary Artist | Courtesy: Swapnil Khullar

Contributor