“Don’t shoot what it looks like. Shoot what it feels like”

David Alan Harvey

As a medium, photography has always maintained its ‘photojournalistic’ ‘news photography’ nature. But Tamil photojournalist and activist Palani Kumar, who uses photography as a tool to give a voice to the ‘voiceless’, sees it beyond its aesthetic appeal and uses it to document and empower marginalised voices. Through Palani Kumar’s activities, we can see marginalised communities coming into focus. In light of Ambedkarite views, it has transformed the neglected lives of marginalised, somewhat voiceless people in society—including fisherfolk, working women, and minorities—into storytelling photos. He has worked to educate and equip them to tell their stories.

Palani Kumar uses his camera and the activism it entails to respond to long-standing forms of oppression. The oppressions, which have persisted for centuries and have become ingrained norms, are so vast that they cannot be captured in a single snapshot; these are the issues Palani Kumar strives to record and disseminate through photographic activism. Palani Kumar, who developed his interest in cinema and photography at an early age, gradually advanced through various stages, and later trained children from marginalised communities to work as photojournalists and more. As photography has always been an inaccessible medium for marginalised communities due to the high cost of equipment, Palani Kumar proposed his ‘photo activism’ by providing cameras for training. ‘I wanted to bridge that gap and make photography more accessible,’ Palani Kumar himself says. Here, the gap is the material resources of the camera, and the privileged and the deprived. Through his photography training classes, children also gain a deeper understanding of social realities.

The aim of photography is not just to capture a scene, but also to portray social realities and bring them to the public to create awareness. Palani, born into a fisherman’s community and having studied engineering at his mother’s wish, who was a fish vendor, began to pay unprecedented attention to issues affecting marginalised communities when he assisted in 2015 with a documentary about manual scavenging and sewer deaths. If the shooting of that documentary made it clear that the lives of marginalised people are worthless and highlighted how deep caste-based discrimination runs, Palani later focused on paying attention to such marginalised issues. He read the works of Dr Ambedkar and Periyar and tried to understand the concept of ‘caste’ more deeply. He realised that manual scavenging is ‘normalised’ in a caste-based social system and that sewer deaths are a failure of that system. From this realisation, his genuine ‘photojournalism’ or activism begins.

The first photography workshop conducted in 2019 for the children of sanitation workers bore witness to the mission of understanding caste through the camera. Palani’s brave initiatives say that ‘Witnessing is an important process — it documents history for future generations.’ When seen through the seriousness of photography as a medium and as documentation, it is the children who realise how much caste discrimination their parents and community face, and, through them, this awareness also reaches the community.

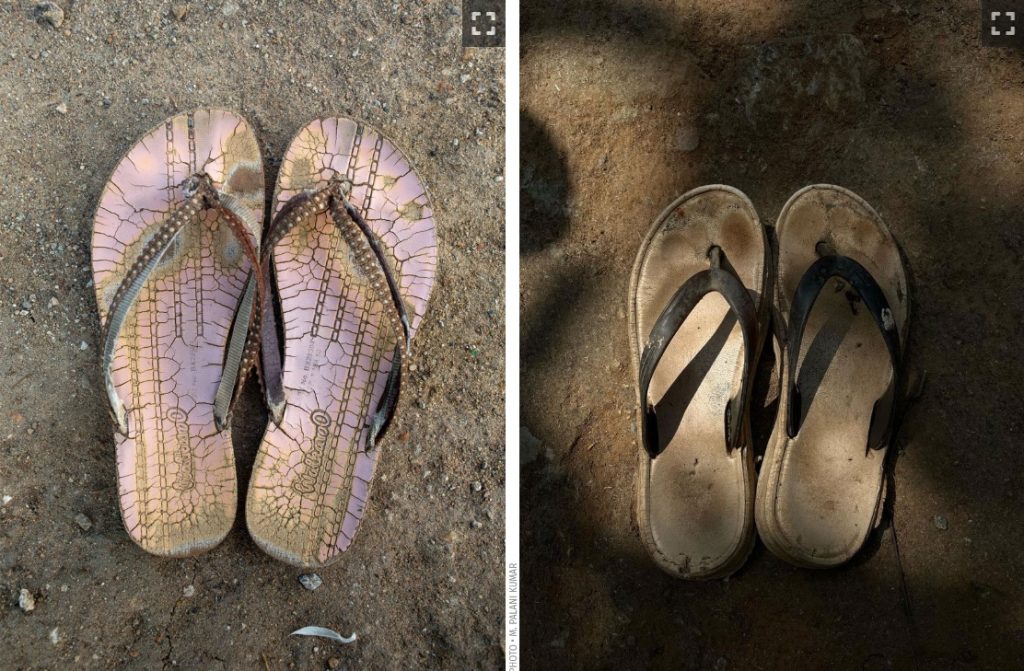

Chappal Story

At Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2022, Palanikumar’s photographs are also part of an exhibition organised by the Chennai Photo Biennale, which was highly engaging. I was the art mediator for that show, and I directly observed and understood the audience’s attitude towards those photographs. It has been seen many times that people from the upper class of society don’t even bother to look at it, and this is where the significance of what Palanikumar does lies.

In a working-class society, especially among those engaged in manual scavenging, it is relevant to ask how their feet and chappals bear the marks of the society they live in and the waste they handle. The work done by manual scavengers, and what they carry on their bodies, is a filthy, messy reality that some people cannot even bear to look at. In this context, Palani Kumar’s photographs act as a mirror confronting these realities. They are not just photographs; they are images that speak the truth.

Even though manual scavenging is illegal, many individuals continue to make a living from it, and many of them die every year. According to the National Commission for Safai Karamcharis, since 1993, 1,054 individuals have been killed as a result of dangerous septic and wastewater tank cleaning. Suffocation from toxic gas inhalation is the most common cause of death among those who clean sewage and drainage systems without wearing protective gear. ‘You are what you wear’ is accurate to some extent, and by looking at the chappals of those who do manual scavenging, one can understand which class or social strata they belong to in society. Most photographers specialise in specific areas. Among various genres like landscape, wildlife, portrait, wedding, and fine arts, Palanikumar stands out not just because he focuses on subjects from marginalised communities, but also because he concentrates on topics that, like workers’ feet, hold no market value at all.

‘The chappal of the Worker’ is one of the things that Palanikumar has observed and captured during his travels across India. It is a depiction of their (waste-filled) workplaces, imprinted with those who have continuously cleaned toilets and drainage systems. Cheap, low-quality shoes — rubber chapals, safety pins stapled, tied, and patched up — are part of every worker’s life. Despite being extremely inexpensive, the fact that even these cannot be afforded is a reality that this marginalised community faces in a society with a pitiful ‘economic condition.’ This is what Palani narrates through his camera. The tragic situation of using a worn-out chapal because there is no money to buy a new one, until it crumbles or even collapses, is perhaps a reality reserved only for marginalised communities.

It is a historical fact that at one time, oppressed communities were not allowed to wear shoes. That situation has now changed. However, the invisible circumstances have still not changed, as Palanikumar’s documentation ‘Of chappals’ shows. The feet of the working people and the chapals they wear are by no means a promising sight, and this is especially true for the feet and shoes of those doing scavenging work. The chapals tell stories not just about the people who wear them, but also something about the society they live in. They reveal how degrading or merciless society has been toward them. But no one other than those who say it will be willing to listen. They are at the bottom of the power structure. It is also a fact that society does not expect them to have a mission greater than cleaning toilets and garbage pits.

Underprivilege is not just a lack of money; it is also a lack of power and a lack of voice against ‘being oppressed’. It is the lack of awareness that their situation has been imposed on them and the lack of strength to respond to it. Slowly, the voice against it begins to emerge. Here, the backdrop is photography. Looking through the camera’s viewfinder, children from the manual scavenging community and others are documenting their own lives with greater focus, framing them and displaying them. That’s how they try to escape from it and overcome it.

Drainage systems in cities often get blocked. Who cleans the clogged drainage systems and restores urban life to normal? For that, we, who consider ourselves an advanced society, create and maintain ‘communities’ at multiple levels. It is those who are rendered untouchable by this so-called advanced society whose lives become the subject and focus here. Palani Kumar uses images that have ten times more power than words. The world of meanings that images can convey is vast and expansive. That is what is being utilised here. The vision and perspective that merge into a single view are evident in Palani Kumar’s photography and activism.

From those who wear torn chappals to those who don’t even have chappals, all are part of our society. Sometimes, it is pitiful to live in a supposedly progressive society that has turned into ‘norms’ where people are identified and segregated based on what they wear, to the extent that there isn’t even space at the edges. Newspapers, media, or art galleries that focus solely on the ‘political ambitions’ of the elite do not leave room for expressions of that untouchability. It is here that Palani Kumar’s long-term efforts, though gradual, begin to make an impact.

The ‘worn-out shoes’ in the series ‘To walk a mile’ speak not only to those who wear them but also about us. Who can slip away, saying that the existing social structure is not their responsibility? Can one let go of it, claiming it as a historical construct? If a historical structure is inhumane, dismantling it is a responsibility of those living in this era! This truth is what Palani’s ‘photography activism’ speaks of.

Paulo Freire mentions in his book ‘Pedagogy of the Oppressed’ that dehumanisation is not only an ontological possibility but also a historical reality. ‘Oppressed’ is a process; while it is an ontological process that one may not recognise in oneself, it is also the historical reality of an oppressed life. Freire asks, ‘Who suffers the effects of oppression more than the oppressed?’ and emphasises the need to see it in multiple dimensions. Through worn-out shoes, through clothing, through the food they eat, through the utensils they use, through the deplorable state of the houses and surroundings they live in, through the schools they attend (or not), through the treatment they receive in public spaces, the oppressed come to realise themselves through these incremental experiences. Being ‘oppressed’ is the experience of dehumanisation, the process of being made less than human while being human. There are many forms of these processes.

‘One of the basic elements of the relationship between oppressor and oppressed is prescription,’ says Paulo Freire, which we can say serves as the introduction to Palani Kumar’s story of the chappal. The term ‘prescription’ is a statement that requires reflection. Prescription has persisted for centuries, in line with the economic and social needs of elites. This prescription may not only be written in some book but may also have become a norm maintained over time. There needs to be action taken against that prescription. That prescription also needs to be deconstructed. Various media and methods will be needed for that. There is no doubt that Palani Kumar’s photography is among the most powerful.

Krispin Joseph PX, a poet and journalist, completed an MFA in art history and visual studies at the University of Hyderabad and an MA in sociology and cultural anthropology from the Central European University, Vienna.