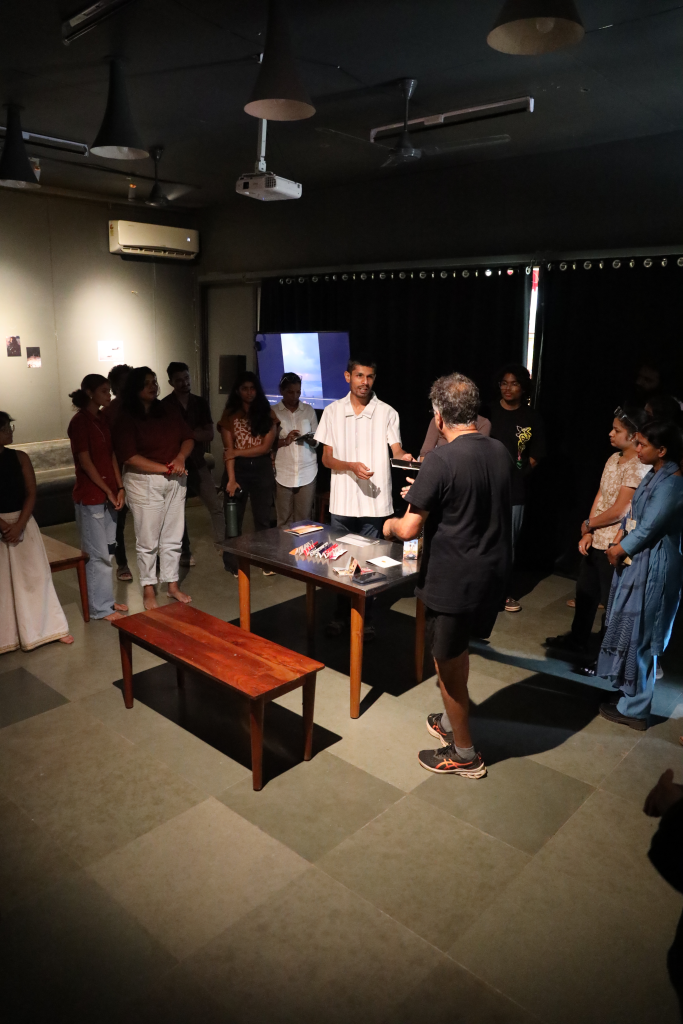

In the heart of Goa, at the intersection of art, tourism, and identity, a quiet shift is beginning to take shape. No, it’s not a new resort or yet another techno festival—it’s something far more intimate, layered, and long overdue. The recently concluded Collaborative Photography Design-a-thon at the Museum of Goa, aptly titled As We Run Through Time, sought to examine Goa not as it is packaged for the outside world, but as it breathes and lives through the eyes of those who walk its alleys, listen to its stories, and feel its silences. Drawing inspiration from conceptual artists like Piero Manzoni and Joseph Beuys—who radically expanded the idea of what art could be—this workshop embraced the belief that every human being is an artist, and that perception is a creative act as much as a sensory one. The project invited eight emerging photographers, filmmakers, and designers to step beyond the default lens through which Goa is often perceived. The idea was both simple and radical: What happens when we interrupt the cliché?

Goa: The Dream and the Disconnect

To speak of Goa today is to speak of two Goas—one imagined, one lived. One exists in travel brochures, party invites, Instagram reels, and Bollywood scenes: golden beaches, swaying palms, cashew feni, EDM nights, and bikini-clad freedom. The other Goa is subtler, textured, sometimes chaotic—defined by its Konkani lullabies, crumbling colonial homes, resistance movements, fishing communities, land struggles, monsoon silence, and everyday negotiations with history. This dissonance between the “marketed Goa” and the “lived Goa” was at the heart of the design-a-thon. The workshop wasn’t about correcting perception—it was about complicating it. It was about asking, what do we choose to see, and what are we trained to ignore? Through guided field visits to Candolim Beach, Aguada Fort, and nearby settlements, the participants were invited to observe not just what stood in front of the

lens, but what sat behind it: their own assumptions, instincts, and inherited clichés.

Perception as Practice

The structure of the two-day intensive was thoughtfully designed. It began with a reflective introduction to the nature of perception—framing it not just as sensory reception, but as an active, interpretive, and often socially conditioned process. Participants discussed how collective thinking shapes visual cultures, and how images are never neutral. This was followed by a visual expedition: participants ventured into the field to gather images, videos, and sounds, not with the aim of “capturing Goa,” but of engaging with it. This meant slowing down, listening deeply, documenting textures, fragments,

overheard conversations, unexpected juxtapositions, and moments of stillness. They returned with portfolios, but mostly with questions—about place, about purpose, about visual responsibility. These questions formed the core of the next phase: collaborative curation. Working together over long, immersive hours, they sequenced their material, layered audio with visuals, and developed a collective script that didn’t

aim to speak about Goa, but rather from within it.

Challenging the Frame

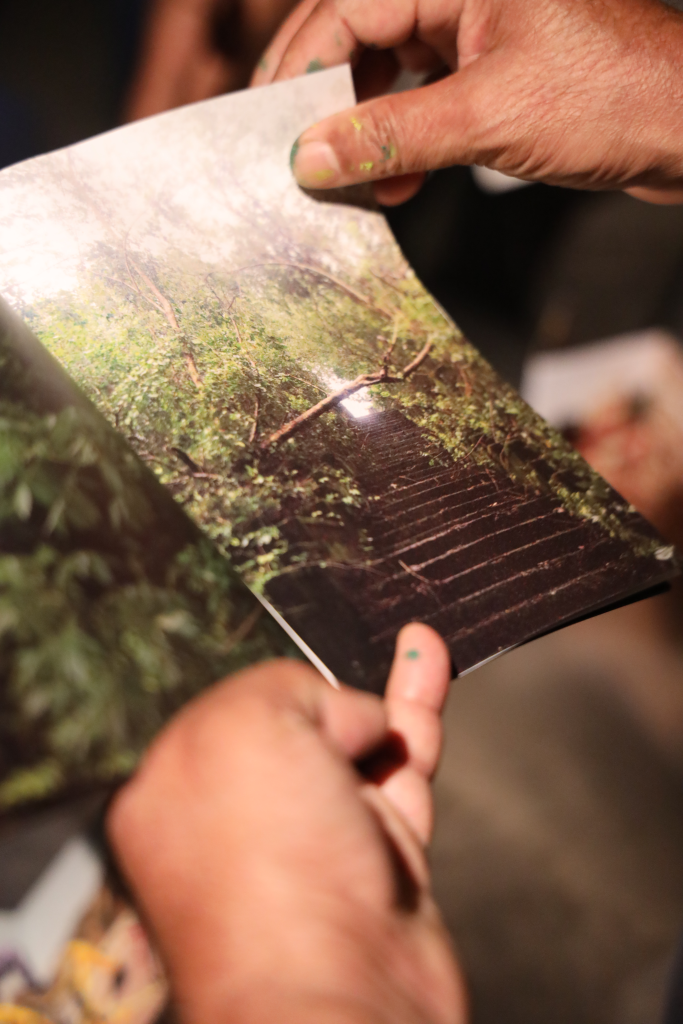

Some of the most striking moments emerged from what the facilitators called “Representing the Cliché.” Participants were prompted to loop stock video clips of beach sunsets while playing audio of Konkani folklore—creating dissonance between what was seen and what was heard. In doing so, they created a haunting, almost poetic split-screen between the Goa that sells and the Goa that sings. In another exercise titled “Fiction in Focus,” participants constructed personal visual narratives—delving into their own connections with places, objects, and memories. These were not documentaries in the traditional sense. Instead, they became speculative visual essays: imagined futures, poetic reconstructions, and visual metaphors

stitched together from lived impressions. Inspired by the works of artists like Walid Raad, Subodh Kerkar, Saumya Shakar Bose, and Sharbendu De, the group leaned into the idea of constructed images—where fiction, memory, and history overlap. One zine reimagined tourism brochures as satire,

combining glitzy headlines with grainy photographs of dried wells and abandoned homestays. Another layered archival newspaper clippings with handwritten notes from locals protesting illegal constructions. These eight zines—playful, powerful, and piercing—were the final outcomes. Together,

they did not offer a singular narrative, but a mosaic. A Goa fragmented and reassembled. A Goa caught in the act of becoming.

The Shift in Love

But perhaps what emerged most profoundly from As We Run Through Time was something far less tangible and far more moving: a shift in the nature of love itself. For decades, the dominant love for Goa has been a consumerist one—fleeting, hedonistic, Instagrammable. It is a love of escape, not engagement. But in this workshop, another kind of love took root. It was quieter. It asked more questions than it answered. It didn’t romanticise Goa as a paradise, nor did it paint it as a victim. Instead, it held space for its contradictions. This love was curious, critical, and creative. It listened to the stories of an old aunt in Candolim remembering the mango trees that no longer bloom. It paid attention to the sound of shutters in closed Portuguese homes, the scent of fish drying on rooftops, the laughter of children who have never been to the beach despite living a kilometre away from it. It was not about discovering the “real” Goa—it was about allowing Goa to speak in multiple tongues.

Artists as Catalysts

At the helm of this transformative experience were two artists and facilitators whose own practices reflect the workshop’s ethos. Preksha, from Aravali, Rajasthan, brings a background in documentary and analog photography, often exploring themes of ecology, gender, and memory through constructed still lifes and found objects. Chaitali, from Sawantwadi, works at the intersection of rural life, storytelling, and visual art, using film and bookmaking to weave narratives rooted in everyday spaces and dreams. Both artists met at NID, Gandhinagar, and their collaboration has always been

community-centric. Their approach to learning is circular rather than linear, intuitive rather than didactic. This workshop was no exception. It wasn’t about teaching participants how to shoot or what to think. It was about creating conditions for perception to evolve. And evolve it did.

Towards a New Visual Culture

The final phase of the workshop was an open exhibition—set up with care and intention by the participants themselves. On display were the zines, photographs, video loops, audio fragments, and bits of conversation that had been woven over two days. Visitors didn’t look at the work—they were invited to read, listen, pause, question, and even add their own thoughts. In a way, the exhibition wasn’t the conclusion—it was the continuation. It posed a quiet challenge: Can we rethink how we see Goa? Can we unlearn what we’ve been sold, and make space for what is?

A Hopeful Aftertaste

As We Run Through Time reminds us that love for a place is not static—it is an evolving relationship. And like any deep relationship, it requires effort, attention, and the willingness to see things anew. In the end, the shift in perception is also a shift in responsibility. When we begin to see Goa not just as a destination but as a living, layered, and contested space, our engagement changes. We move from being passive consumers to active co-dwellers,

from photographers to storytellers, from tourists to listeners. And perhaps, that is the most important takeaway of all: to truly love a place is to allow

it to change you. As we run through time, Goa does not wait, but it does whisper if we are willing to hear.

Featuring Image Courtesy: Museum of Goa

Nilankur believes in the magic of critical thinking, intelligent dialogue and creativity. He stays in Goa, programs for the Museum of Goa and is a columnist.