The artistic questions posed in “Like Gold”, a collateral project of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, such as Cop Shiva’s Being Gandhi, are anything but static depictions; instead, they represent a rigorous re-negotiation of the Indian story. The artworks of “Cop Shiva,” a photographer-artist who works as a police officer during the day, navigate the bureaucracy and hardships of the Bangalore police force. He reconstructs the world via a viewfinder at night, or maybe during the peaceful intervals between the sirens. Cop Shiva doesn’t just document life; he arrests it, proving that the rigid uniform of a policeman is no match for the fluid gaze of an artist. Cop Shiva’s photography works on a frequency that his police radio never reaches, whether he is photographing a man turned into a shimmering silver deity or the serene dignity of a village schoolteacher. He is an artist of dualities, a guy entrusted with upholding law and order who draws most of his inspiration from the stunning, chaotic theatre of the human spirit.

The genesis of the name “Cop Shiva” points to a deep ontological convergence; his artistic identity is inexorably linked to his beginnings in the state apparatus rather than a break from his prior professional existence. This trajectory signifies a dramatic divergence from established creative traditions. His 2001 induction into the police force, which brought him from the rural landscapes of Karnataka to the urban congestion of Bangalore, set the stage for his eventual creative transformation by traversing the space between civic obligation and the 1. Shanthiroad art collective, his post-2010 rise to prominence as a unique practitioner signifies not just a change in profession but also a sophisticated reconstitution of the self as seen through the eyes of the urban spectator.

The practice of Cop Shiva, whose exhibition history includes important South Asian venues such as the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, the India Art Fair, and Chobi Mela, Bangladesh, serves as a rigorous artistic quest into the fragmented topographies of rural and urban India. His work goes beyond simple documentation, establishing portraiture as a place where the intricacies of the subcontinental identity are examined and exposed. The conflict between the masquerade and the ontological separation between the public and private selves is fundamental to Shiva’s philosophical framework. He captures the shifting roles his subjects assume as they move through social and political spheres by navigating the theatre of the ordinary.

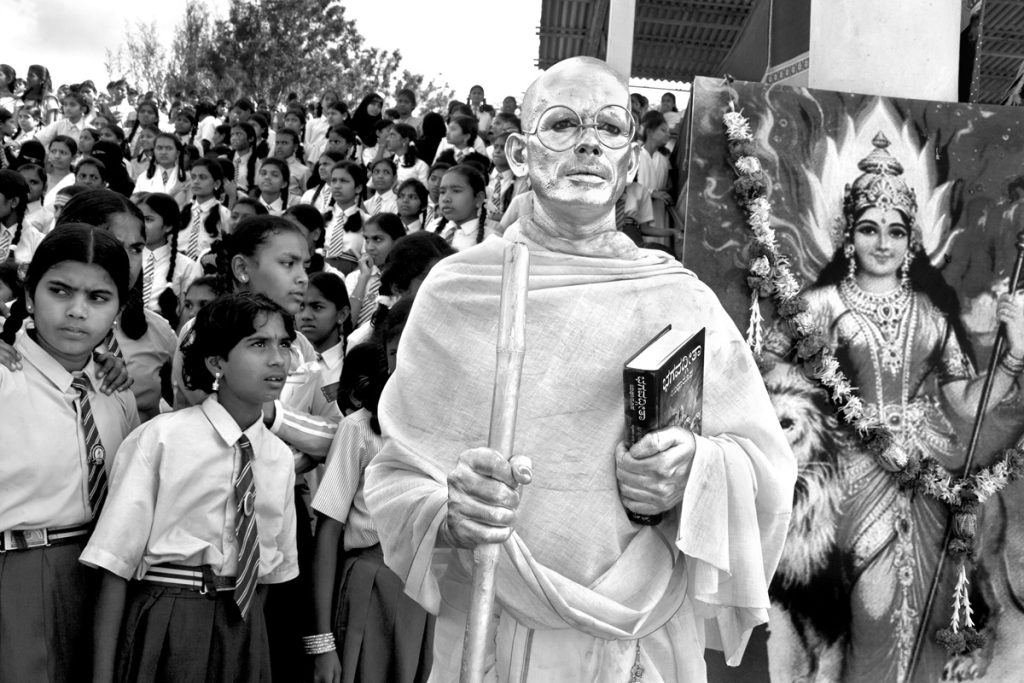

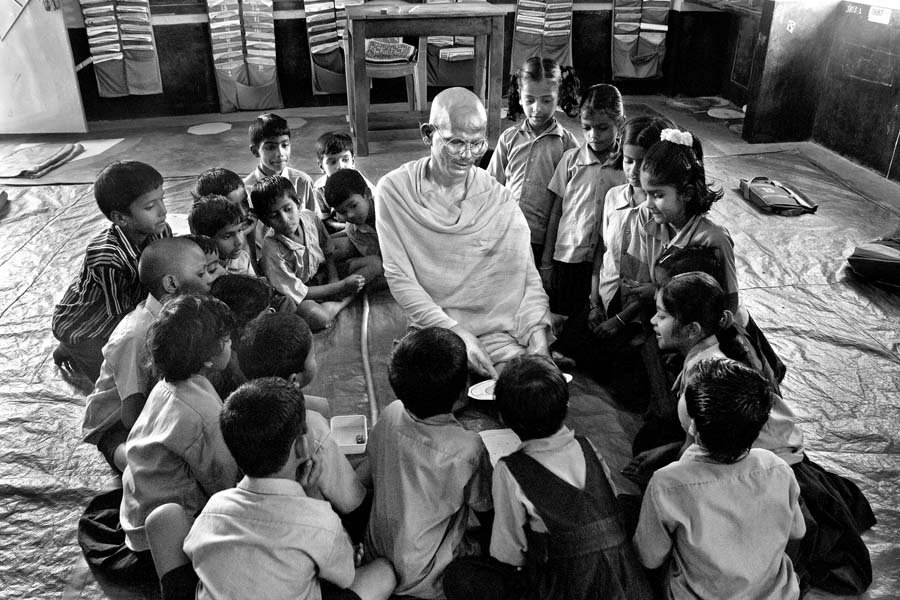

His long-term study of Bagadehalli Basavaraj is the most profound manifestation of this investigation. Shiva turns a local act of political action into a more comprehensive philosophical reflection on the symbol’s enduring power and the radical possibilities of the “performed” body in the modern world by chronicling the rural school teacher’s constant Gandhian impersonation.

Cop Shiva’s photographic series Being Gandhi is an essential intervention in a moment characterised by the growing urgency of Gandhian praxis, reviving Gandhi within the context of modern Indian sociopolitical discourse. This visual investigation prompts a more thorough examination of the medium’s ontology. In contrast to the famous statement made by American formalist Ansel Adams that “there are no rules for good photographs, there are only good photographs,” Shiva’s work implies that an image’s “goodness” is determined by its capacity to go beyond simple aesthetics and acquire a significant semiotic weight.

Examining the trajectory of Cop Shiva’s work reveals a deep obsession with the peripheral topic. His work serves as a critical investigation of the lives of people living in the liminal spaces of urban-rural conflict, such as itinerant performers, urban migrants, and practitioners of non-normative lifestyles. This series of intimate portraits signifies a significant epistemological change in modern art; in that sense, Shiva enacts a twin movement of visibility and inclusion by placing these marginalised bodies within the canon of fine art.

Gandhi and Being Gandhi

Shiva’s Being Gandhi navigates the conflict between his hagiographic elevation and modern erasure while placing itself within the broad ontologies of Gandhian philosophy. The project serves as a diagnostic lens through which the Indian landscape is refracted into a performative documentation. By focusing on the Gandhian subject, Shiva performs a critical mimesis, using Gandhi’s teleological vision for India as a mirror to address the contradictions of the present rather than just imitating a historical figure.

The disparity between ‘Gandhi’ as a historical signifier and ‘Being Gandhi’ as a performance, and the documentation of that, reveals a profound ontological tension—a dialectic where, as Marx posited, ‘everything is pregnant with its contrary.’ This inherent contradiction generates a liminal space in which the performance does not merely replicate the icon but instead interrogates it. The resulting dialogical friction between the ideal and its enactment deepens the discursive complexity of the contemporary moment, particularly given the great ideal’s current stature.

By dissecting Gandhi as a static ideological fixture and reimagining him as a material presence—a living incarnation manifest in the physical world—this project represents a critical historical intervention. By uncovering the human embodiments of Gandhian ethics, the work proposes that the reclamation of the national “atman” (soul) is predicated upon a radical expansion of the ideal, moving beyond hagiography toward a tangible, lived reality.

The latent roots of Gandhi’s philosophy—sown deeply into the cultural substratum—demand further excavation; even yet, the simple revival of his ghost is insufficient to negotiate the complexity of India’s current malady. In this sense, Shiva’s Being Gandhi serves as an essential catalyst; it suggests that ‘Gandhi’ is an active ideological program—a flexible methodology intended to be reactivated through collective participation and public praxis—rather than a static historical figure to be worshipped.

Retaking Galaxy of Musicians

A crucial link between nineteenth-century courtly aesthetics and the current public realm is made possible by the modern re-curation of Raja Ravi Varma’s groundbreaking 1889 canvas, Galaxy of Musicians. The piece, commissioned by the Maharaja of Mysore and now housed in the Jaganmohan Palace, has long served as a pillar of gendered representation and Indian nationalist identity. Cop Shiva, however, initiates a crucial socio-aesthetic intervention through the project ‘Retake: Galaxy of Musicians’, which challenges the original tableau’s exclusionary nature and questions Varma’s idealised vision of pan-Indian harmony’s conspicuous lack of the “commonplace” or subaltern subject.

In the series Retake: Galaxy of Musicians, Raja Ravi Varma’s subjects undergo a centennial migration, transcending the gilded confines of the nineteenth-century frame to engage with the contemporary subaltern. Through the deployment of large-scale cut-outs, the work collapses the distance between the classical canon and vernacular life. As these figures embark on a peripatetic journey through urban and rural landscapes—intersecting with fish vendors, construction workers, and local youth—the project instigates a radical re-reading of ‘the classical.’ It effectively dissolves the boundary between historical artefact and contemporary social practice, questioning how the classical gaze survives when confronted by the grit of the everyday.

The ‘Classical’ functions as both a monumental signifier and a restrictive historical category; here, it undergoes a rigorous interrogation through the mechanics of reproduction. By centring the ‘ordinary’ subject—so often erased by the systemic myopia of historical documentation—this project addresses a profound historiographic void. The trajectory of the Galaxy of Musicians serves as a site of aesthetic and political transformation, embodying Deleuze’s theorem that ‘articulation is double.’ In this re-envisioning, the content is not merely mirrored but bifurcated, creating a ‘double’ that disrupts the original hierarchy and activates a new, pluralistic mode of expression.

Cop Shiva uses forensic vision, trained to identify the marginal, the abnormal, and the socially dissonant, drawing on his law enforcement experience. However, in his practice, this visual accuracy goes beyond simple observation to become a profound act of witnessing. By recognising that reality is rarely singular or final, Shiva uses his projects as speculative tools to analyse the intricate, multidimensional nature of the modern social fabric. His work serves as a silent, existential investigation into the self.

Contributor