The Rajkumari Ratnavati Girl’s School in Rajasthan’s Thar Desert is an oval-shaped stone structure that has become both celebrated icon and contentious symbol in contemporary socially-engaged architecture. This $280,000 project by New York architect Diana Kellogg demonstrates how thoughtful design can directly address social barriers while raising complex questions about the relationship between architectural ambition and community needs.

In a region where female literacy hovers at just 32-36%—India’s lowest—the school serves 400 girls across a 13-kilometer radius, transforming both landscape and lives.

The school’s location in one of India’s most educationally disadvantaged regions gives urgency to its mission. Since opening in 2021, it has enrolled girls from seven communities, providing free education, transportation, and meals in an area where economic barriers and cultural resistance traditionally prevent girls from attending school.

Form follows social function

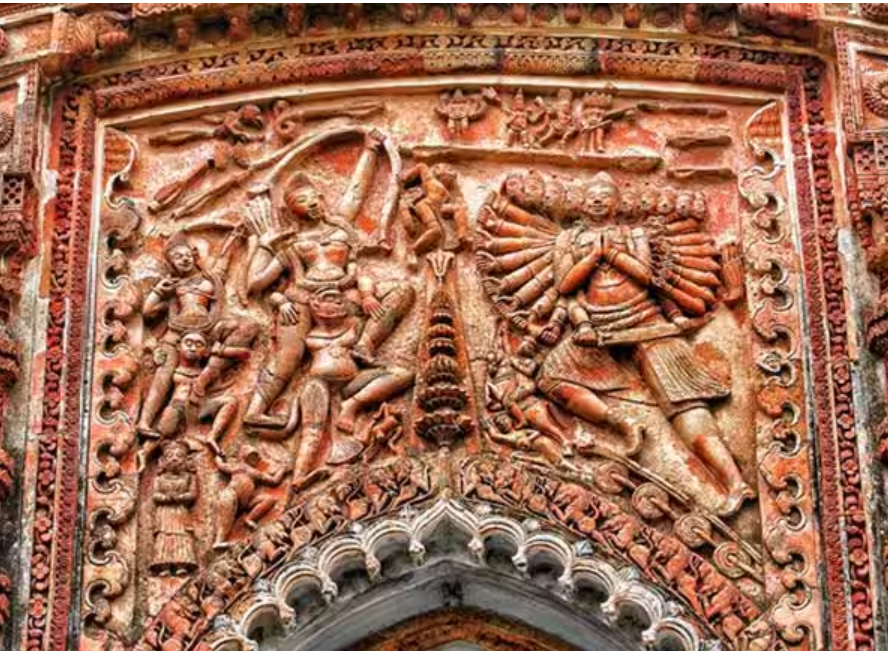

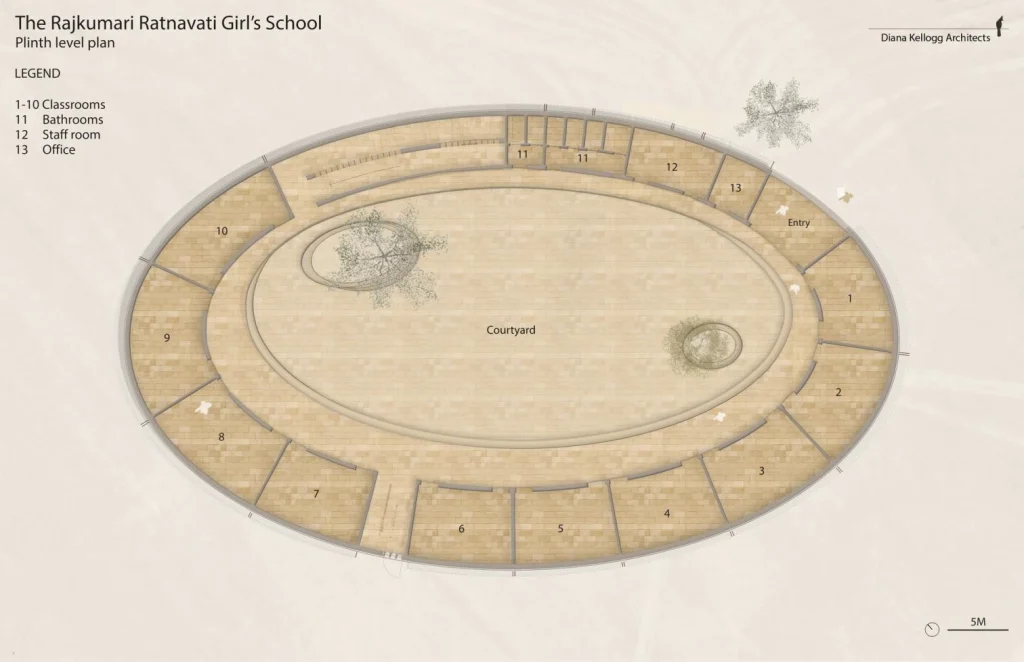

Kellogg’s architectural approach centers on the radical premise that building form can directly enable social transformation. The school’s elliptical shape—200 feet by 120 feet of hand-carved Jaisalmer sandstone—was deliberately chosen to represent “femininity, infinity, and strength across cultures,” according to the architect. The curved walls create protected courtyards where girls can play freely while maintaining the privacy requirements of local purdah traditions.

The design’s most innovative social feature lies in its reinterpretation of traditional jali screens—latticed stone walls that simultaneously provide climate control and cultural appropriateness. “I wanted to make a building about space and light and community and not about design—a structure that resonated with the soul and femininity,” Kellogg explains. These screens address one of the fundamental barriers to girls’ education in conservative communities: the need for modesty and protection from external observation.

The building’s spatial organization reflects deep understanding of how architecture can overcome cultural resistance. Central courtyards provide familiar family-centered environments, while the single-story accessibility removes physical barriers. The oval form eliminates hierarchical corners and dead-end spaces, creating fluid circulation that encourages interaction and movement—essential for girls who may be experiencing their first taste of educational freedom.

Climate as social equity

The school’s environmental design directly serves its social mission by making education physically comfortable in a climate where temperatures reach 50°C. Thick 380mm sandstone walls provide thermal mass, while lime plaster interiors create natural cooling—architectural strategies proven over centuries in Rajasthani vernacular buildings. Solar panels not only provide reliable power in a region with frequent outages but double as playground equipment, creating shaded outdoor spaces that extend usable area.

These climate-responsive features demonstrate how environmental sustainability and social equity intersect. When local contractor Kareem Khan reports that the building stays comfortable without air conditioning, he’s describing an economic achievement as much as an environmental one. The natural cooling systems enable year-round education without energy-intensive mechanical systems, making the school financially sustainable for communities living below the poverty line.

The building’s rainwater harvesting capacity of 350,000 liters annually addresses water scarcity while teaching environmental stewardship. Diana Kellogg worked entirely with local craftsmen—often the girls’ fathers—using traditional hand-carved stonework techniques, creating community investment in both construction and ongoing maintenance.

The limits of symbolic architecture

Despite international acclaim and multiple awards including the 2023 AIA Architecture Award, the project faces substantial criticism regarding its architectural approach and long-term effectiveness. The Architectural Review’s analysis identified fundamental climate performance issues, noting the school “struggles to mitigate north-western India’s extreme temperatures.” While measurements show a six-degree temperature difference between courtyard and classroom, critics argue this insufficient for extreme desert conditions.

The project’s representational aspects prove its weakest element: the connection between oval form and “universal feminine symbols” strikes critics as superficial when divorced from specific local cultural meanings. The building’s prominence as “a striking object, not keen to recede into the landscape as vernacular structures do” prioritizes photogenic architecture over contextual integration.

Alternative models reveal different possibilities

The comparison with the now-defunct Lok Jumbish project (1992-2003) reveals dramatically different approaches to educational architecture in the same region. Lok Jumbish employed extensive community participation, with architects like Sanjay Prakash living on-site and facilitating Village Construction Committees in designing hundreds of schools across 40,000 villages. Their focus on “modern vernacular buildings” rather than architectural statements achieved better local ownership and maintenance.

Lok Jumbish demonstrated that sustainable educational infrastructure requires community involvement in design decisions, not just construction labor. The participatory approach built local capacity for ongoing maintenance while creating schools that truly reflected community needs and cultural values. Their success suggests that the most effective socially-engaged architecture may prioritize process over product, capacity-building over iconic design.

Other contemporary models like Francis Kéré’s African school projects show how international architects can successfully integrate local materials and techniques while addressing climate challenges through deep community engagement and extended site presence.

Community voices complicate the narrative

Local responses to the Rajkumari Ratnavati School prove more nuanced than either critics or supporters acknowledge. Michael Daube of CITTA reports that “communities have embraced the building and the girls are happy to be at the school,” with high attendance rates confirming community acceptance. The employment of local craftsmen, including fathers of students, created genuine community investment in the project’s success.

Yet the top-down design process contrasts sharply with participatory approaches. While Kellogg consulted with local stonemason Kareem Khan on technical details, there’s limited evidence of broader community input on spatial organization, programmatic needs, or cultural appropriateness. The project originated from a New York-based architect working pro bono for a US nonprofit, raising questions about whose vision the building truly represents.

Student testimonials remain largely absent from public discourse, though visitor accounts describe girls “running around and across the oval-shaped building, which echoed their voices.” This image of joyful occupation suggests the architecture successfully creates welcoming environments for learning, even if the process excluded student voices in design development.

Architecture’s power and responsibility

The Rajkumari Ratnavati Girl’s School embodies both the promise and perils of architecture as social intervention. Its success in creating educational opportunities for previously excluded girls demonstrates design’s genuine potential to enable social change. The building’s climate-responsive features, cultural sensitivity, and community engagement represent sophisticated responses to complex challenges.

Future socially-engaged projects might learn from both the school’s achievements and limitations, seeking approaches that combine genuine community participation with architectural innovation rooted in local knowledge and climate realities. The goal should be architecture that empowers communities to create their own transformative spaces, rather than beautiful buildings that merely house social programs.

Athmaja Biju is the Editor at Abir Pothi. She is a Translator and Writer working on Visual Culture.