An exhibition without audience is absurd. But are all exhibitions meant for everyone? A drama festival is for drama lovers, a film festival is for cinema enthusiasts, and literary festival are for those who enjoy literature. Each exhibition targets its specific audience. Looking at it this way, who is the ‘audience’ of Kochi-Muziris Biennale? Exhibitions are evaluated as products of modernity. All major exhibitions in the world function as part of modernity. The Biennale, which started in Venice and has spread worldwide, also has a targeted audience behind the culture. This is what is being examined here.

Modernism has evolved and developed at many levels; as Habermas (1991) stated, modernism is a bundle of cumulative and mutually reinforcing processes, such as establishing centralised political power, the formation of national identities, the proliferation of the right of political participation, the conditions under which urban life has been made possible, school education, and new values (p. 2). Habermas gives an idea of distinguishing the new modern world from the old world: ‘it opens itself to the future; the epochal new beginning is rendered constant with each moment that gives birth to the new’ (p. 6). In applying a new language, as Habermas states, the ‘historical objectification of rational structures’ (p. 2), modernism is the birth and opening to the future.

When it says that modernism opened the door in many ways, sharing his thoughts on modernism, Weber (1976) speaks of the advent of modernism by considering the nation as a cultural unit (p. 95). In Weber’s arguments about schooling, which Habermas himself refers to as one of the hallmarks of modernism, there are accurate observations of the role played by school and education (pp. 303–338). Following Weber’s arguments between education and modernism, I examine the relationship between art and the audience — considering the (art) audience as an imagined community formed through education — and how it represents modernity. The attempt is to see the audience participating in art exhibitions, as Weber himself describes them, as shaped by schooling, as an integral part of a total process of modernism (p. 303).

Cosmopolitan Kochi Muziris Biennale

Based on my views while serving as an art mediator at the Kochi Muziris Biennale 2020–21 edition, which is considered Asia’s most influential contemporary art exhibition located in Fort Kochi and Mattancherry, Kerala, in the southern part of India, I aim to disentangle the relationship between modernism and audiences. There are two main things which are apparent from the audience at the Biennale: one is the educated- middle- upper-class-only those who are adequately educated enough to sufficiently embody and recognise the art world, which is displayed in various formats- representations, and second, the fact that they perceive and identify themselves as an imagined community of ‘art lovers’ and how the Kochi-Muziris Biennale space was converted into an exhibition space of art and audience same time. The first Biennale was connected and curated in two historic port cities of Kerala- Fort Kochi-Mattancherry- and came with the tagline ‘India’s First Biennale’; through another tagline ‘People’s Biennale’, it was relegated to the popular arena, where communist ideologies have significant roots.

The language proposed by the Kochi Muziris Biennale, which the Communist government initiated, was extremely popular and widespread. In addition to English, the Biennale was implemented through popular aspects by introducing vernacular language brochures and implementing outreach programmes. For example, photography of autorickshaw drivers, street vendors, shopkeepers, and pedestrians with ‘It’s My Biennale’ posters (D’Souza and Manghani: 2017, p. 5) attracted particular attention and made clear its popular and widespread face put forward by the Biennale’s first edition in 2012. However, my argument is that the Biennale’s attempt to keep the local community together is nothing more than a mere attempt to popularise a fair held for the first time, especially the experience of working as an art mediator in the fifth edition (2020–2022), which has convinced the local community that the Biennale is an event and a matter of things that are not so well understood.

The Biennale culture is contained in the language put forth by the Biennale, its source history, which is associated with the Empire Exhibition and is re-positioned when it comes to the artwork as a purely aesthetic experience, an ‘experience marketing’ (p. 7) in a historical city’s heritage and tourism. Western hegemony over art forms is evident elsewhere, and counter-narratives against Western modernism are also being created (p. 8) elsewhere. Biennale is a global platform; its language carries that uniqueness, which must be why the audience it creates is an imagined community. It is the identity of the event called the Biennale itself, its design itself, that creates or mobilises an elite imagined community that is being created.

The observation that the Kochi Biennale is a unique symbol of Indian modernity is intense. While it is true that the Biennale is also a reflection of India’s growth as an economic power and the space that Indian artists have gained in the art market, it must also be said that the Biennale might well be construed within a corporatist model, as a form of experience marketing (p. 10). When the Biennale reflects the Indian mind’s quest to become a global economic power, shedding colonial burdens (p. 11), the question of what kind of audience it created is also raised. For instance, given my experience as an art mediator at the Biennale, a ticket show, it is clear that the mass that came together was an educated middle-class and upper-class community in India and abroad. At the Biennale, once a week, on Monday, entry was free, aiming to bring the local community. However, it has been noted that the time spent by the local community in the exhibition space is very short. The language that engages with artworks, how art is to be understood, and the lack of art education in the local community are reflected in the exhibition space. It is in this context that D’Souza’s observations become relevant, particularly the conclusion that the Biennale is a reflection of India’s post-independence modernist vision, the observation that the Biennale is a declaration that it is India’s economic, political and cultural power, established through an art event (p. 27), also makes it crucial to the audience it shaped.

The theme of the first Indian Biennale itself was cosmopolitanism, and according to the observation of Indian art critic Geeta Kapoor, with its intensity of modernist views shaped by the post-colonial exchanges that have taken place since the colonial period (2012), the event, which was held in the elite language contained in the concept of the Biennale, was made possible by the hybrid of its participants. Where do the cosmopolitan and local, who argue for the Biennale, come together? What more is there than that local is a venue, and cosmopolitan is a liberal-capital rhetoric in that local space? The question of what cosmopolitan conditions the Biennale created beyond an elite class statement with the language at hand for the plaintiff is valid. It is doubtful what cosmopolitan conditions were created, other than that the neo-capitalist school of thought, which sees art only as a capital-derived product, is implemented in a new language. The concept of cosmopolitanism put forward by the Biennale, including the idea of the ‘global’, which came into being in its design, has alienated those who are not ‘cosmopolitan’. For example, going through the arguments of Sandip Κ Luis (2014), one would be convinced that cosmopolitanism is a problematic statement. The possibility of a cosmopolitan argument exists in the unique atmosphere created by the unique demography and caste of the region where the Biennale is being held, Kerala. How can the Biennale put forward its claim of being cosmopolitan in the context of the intense inequality of caste and gender and the dominance of religious organisations in cultural and educational policy-making and implementation (p. 56)?

Take the name of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale as an example. The name Kochi Muziris Biennale, after the ancient port of Muziris, along with the name Kochi, deserves special attention because of the presence of the ancient port of Muziris whereby the active history of the port, which had active trade relations with the West until the 13th century, and the cultural, political and economic hegemony that emerged thereby is added to the art exhibition as a flavour. The cosmopolitan history of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, a historical event, lies in the embodied trade history. Luis argues that the history of the port town of Muziris, which the Biennale proposes, has been even distorted. The author’s argument that Muziris also advances a history of Brahminical hegemony over Buddhist traditions refutes Biennale’s cosmopolitan argument (p. 56).

How can some elite-class artists, like the feudal nobility, create a cosmopolitan character in their art and life, and how can it be attributed to a region? The work of artist Atul Dotia, who was showcased at the first Biennale, is the personal photography collection of an artist with friends in a cocktail party with artists and buyers in Delhi and abroad, the cosmopolitan life of the artist with expensive cars and friends, is the place to show the cosmopolitan life of the artist to a region and thus show the locals what the cosmopolitan is all about. Rebecca M. Brown, of the cultural programs of countries in the United States, including India, in the 1980s, says they were carried out as part of an effort to boost international trade. When talking about the dimensions of Indian exhibitions held in the US during the Cold War period, Brown makes it clear that they were projects with economic and political dimensions (p. 338). While it is clear that the exhibitions are not necessarily intended to be directly stated, when exhibitions such as the Biennale come up with cosmopolitan arguments, what is argued, especially by imposing middle-upper-class pretensions into one region?

Exhibition and Audience

The relationship of the word exhibition with the museum concept is profound, and it is only when the meaning of the word museum is combined that it becomes clearer what the Exhibition is all about. The Latin-originated word ‘museum’ means ‘place of learning or study’ (Heesen, 2018, p. 59). Similarly, the Greek term refers to a site at which the muses were revered and worshipped, and that place is also associated with the expedition (p. 60). A laboratory experience is obtained through exhibitions; Mega exhibitions such as the Biennale are apt for the term laboratory, especially as an art exhibition that is more nuanced, such as installations and conceptual art.

The word museum is associated with the study, a place where there are objects to be carved, and that is where it is possible to study, which makes the museum the centre of worship (p. 60). While, in a way, art exhibitions are spaces for learning about their respective times, and while exhibitions such as the Biennale are the ones that help to capture contemporary and its political and social interplays through works of art created by contemporary, one wonders how artistic the dimensions beyond that, the language it advances, and the world in which the works of art are shared through that language. Heesen describes exhibitions as “displaying or holding up to view’ (p. 61). At the same time, the expositions represent progress (p. 61) and modernity. When that happens, it can be seen that the first Indian Biennale, as stated above, represents Indian modernity.

The idea of an exhibition must be understood as part of a cultural context that establishes its parameters and the content it will display (p. 62). The subject of what kind of audience an Exhibition attracts comes up here. The Biennale’s assertion that local space is being transformed into a global space is noteworthy due to the local population’s intellectual absence. The residents know that the Biennale is a worldwide event carried out locally. The primary source of income for the residents, which is tourism potential, is the money that visitors from far and away spend on room rent and taxi/autorickshaw fares. The existence of the event itself is called into question by the fact that the local is only the venue, its history and geography, and that the locals remain only the people who are indirectly benefited by the event being held.

The Exhibition offers glimpses beyond the reputation of the Empire Exhibition that the Biennale carries; for example, Helen Langa (1999) writes about the social mission of the Exhibition in a racist context. In New York City in 1935, the social interaction of art was carried out through exhibitions aimed at protesting lynch violence (p. 11). Lanka argues that the Exhibition was a long-term plan to sow the seeds of social justice to the people through art.

While the Exhibition was primarily aimed at lynch violence, the literature that emerged as part of that Exhibition exposed the contemporary social situation with extreme observations. In this way, lynch violence has been turned into a social problem. Lanka (p. 14) argues that the 1935 exhibitions occurred at such depth. Herein lies the relevance of the cosmopolitan argument put forward by the Kochi Muziris Biennale. The arguments that need to be raised follow the argument that cosmopolitanism is a social set aside to be put forward, and, more specifically, while advancing Indian modernity in the sense of the Kochi Muziris Biennale Exhibition, it also advances the cosmopolitan hangover of feudal attitude in the Indian social structure. The social relevance of exhibitions and the atmosphere of intellectual debate they can put forward is set aside in the arguments for cosmopolitanism. From the first Biennale to the fifth Biennale, where I worked as an art mediator, one of the exhibitions highlights the audience that shaped it. That the Kochi Muziris Biennale has managed to mobilise a modern Indian audience is attested by the crowds that come during each Biennale, and the money they spend is exemplified to establish that the Biennale is a historic success. For example, the 2017 Kochi-Muziris Biennale Impact Assessment Study is said to be two-get inspired or intellectually stimulated by a good percentage of the audience coming in.

D’Souza (2017) argues that if the relevance of the Kochi Muziris Biennale is to be understood, it needs to be understood that the attempt at international recognition of post-independence India is relevant (p. 30). It can be seen that the Biennale was aimed at showcasing the growing artistic taste of Indian artists who have gained more international attention and the art world, centred on metro cities, which can be called purely cosmopolitan. The mission is to present the idea of the Biennale, the creation of the West, as part of the Global South’s Cosmopolitan Life. Cultural production and its conception have become a global theme, even the event curated in local space, and the Kochi Muziris Biennale attracts more audiences than the Venice Biennale (p. 33. It is the thought of cosmopolitanism that Kochi Muziris Biennale was put forward as the idea of its first Biennale, and tried to follow in later biennales. While every Biennale brings in a new curator and theme, the Biennale has managed to turn what is cosmopolitan into a whole theme. In that context, the thoughts of the audience created by the Biennale and the argument as to how that audience assimilated the cosmopolitan aesthetics put forward by the Biennale should be examined. Does that cosmopolitan argument convert local space into global space or create a temporary global space in local space?

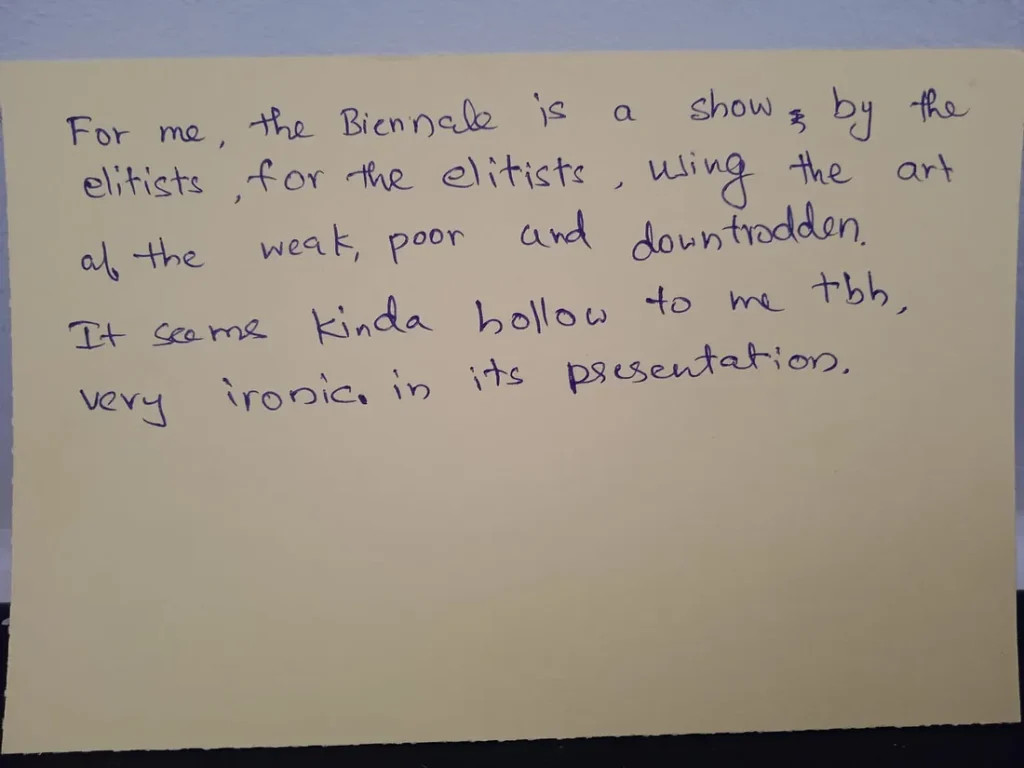

However, beyond the cosmopolitan arguments put forward by the Biennale, it is clear that the local people, as is evident in the Kochi Muziris Biennale Assessment, are coming from intellectual inspiration and curiosity. This is also evident in D’Souza’s argument: notable audience figures might be attributed to a more expansive audience made up of a larger contingent of local visitors and not just reliant on the middle–class, informed, cultural consumer or the wealthy global ‘art tourists’ (pp. 33–34). While it is a fact that a local audience has been created, the reality is that that local audience is a highly privileged community in that area. While working as an art mediator, I realised that many who come in as a local audience are art, architecture and design students or people interested in research. For example, a project at the Exhibition, where I worked as an art mediator, had a system to send letters to visitors on a postcard. About 5,000 people took advantage of this facility. One of the letters describes the Biennale and the kind of community it produced. Be convinced where the local community that D’Souza spoke of is actually from.

It can be seen that the strategic quality (p. 36) of the selection of Fort Kochi and Mattancherry, which found a place on the international tourism map for organising the Biennale, was transformed into a cosmopolitan experience. The postcard someone wrote describes the audience, which refers to underrepresentation. When this postcard answers that intellectual marginalisation is evident, my experience as an art mediator does not mean anything else. I used to give five to ten art tours daily, five to ten people in each group, and I gave more than a thousand art tours during the five-month-long Exhibition. From this experience, it can be seen that the Biennale was mainly attended by an audience from the upper strata of society, with education and cultural capital. It is also clear that there is no difference between local, domestic and international. There is an intellectual stream between the audience, which is the locality that arrives at the Biennale, so that they can interact with a domestic/ international audience. In that sense, the Biennale was created as a cosmopolitan space of people of the same intellectual level scattered over many places.

The letter above is also written in the Kochi Muziris Biennale, which boasts of being able to reach out to the local audience. In that letter, it is clear how elite it is, the language the Biennale presents in the name of cosmopolitanism. That elite space is created by the audience who come to see the Biennale; that is how that language is completed.

Bibliography

Brown, R. M. (2014). A Distant Contemporary: Indian Twentieth-Century Art in the Festival of India. The Art Bulletin, 96(3), 338–356. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43188884

Eugen Weber. 1976. “Civilizing in Earnest: Schools and Schooling” Pp. 303–338 in Peasants into Frenchmen. The Modernization of Rural France, 1870–1914. Stanford.

Jürgen Habermas. 1991 [1985] “Modernity’s Consciousness of Time and Its Need for Self- Reassurance” Pp. 1–22 in Habermas, The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity. Twelve Lectures. Cambridge: MIT Press

Kapur, Geeta. (2012). Kochi Muziris Biennale: Site Imaginaries. Critical Collective. criticalcollective.in

Langa, H. (1999). Two Antilynching Art Exhibitions: Politicized Viewpoints, Racial Perspectives, Gendered Constraints. American Art, 13(1), 11–39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3109305

LUIS, S. K. (2014). Disappearing Strands of Historicity: Critical Notes on the Kochi-Muziris Biennale. Economic and Political Weekly, 49(20), 55–61. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24479708

Robert E. D’Souza and Sunil Manghani. India’s Biennale Effect: A politics of contemporary art. Oxon: Routledge, 2017.

HEESEN, A. (2018). On the History of the Exhibition. Representations, 141, 59–66. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26420636

Krispin Joseph PX, a poet and journalist, completed an MFA in art history and visual studies at the University of Hyderabad and an MA in sociology and cultural anthropology from the Central European University, Vienna.