The Klimt Controversy: Prince William Nii Nortey Dowuona Sparks International Debate

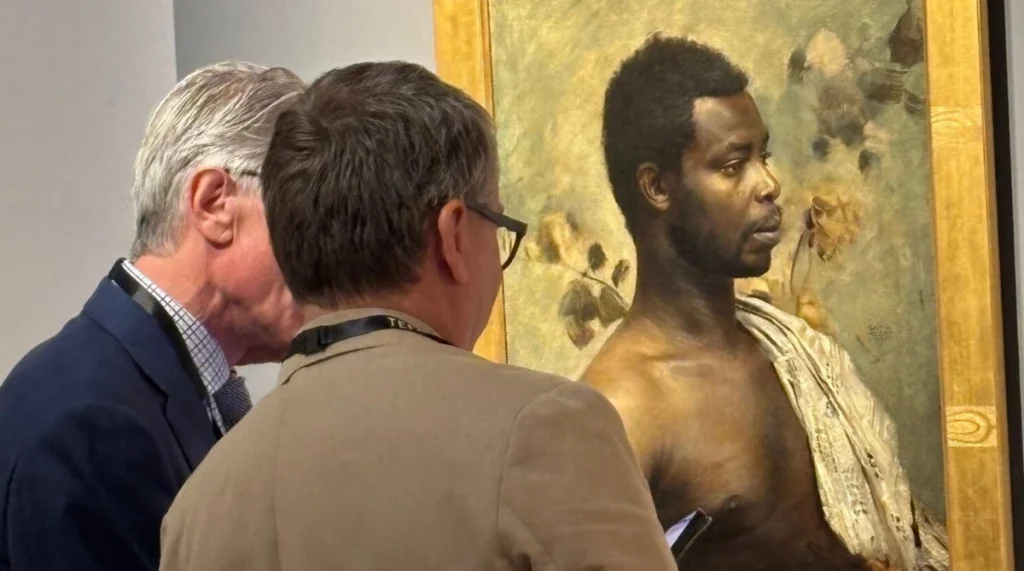

A long-lost Gustav Klimt portrait of Prince William Nii Nortey Dowuona has ignited a firestorm of controversy following its recent appearance at TEFAF Maastricht 2024, where it was offered for €15 million ($16.4 million). The rediscovery of this artwork not only reignited global interest in Klimt’s legacy but also triggered allegations of illegal export and raised serious questions about cultural heritage laws in Hungary.

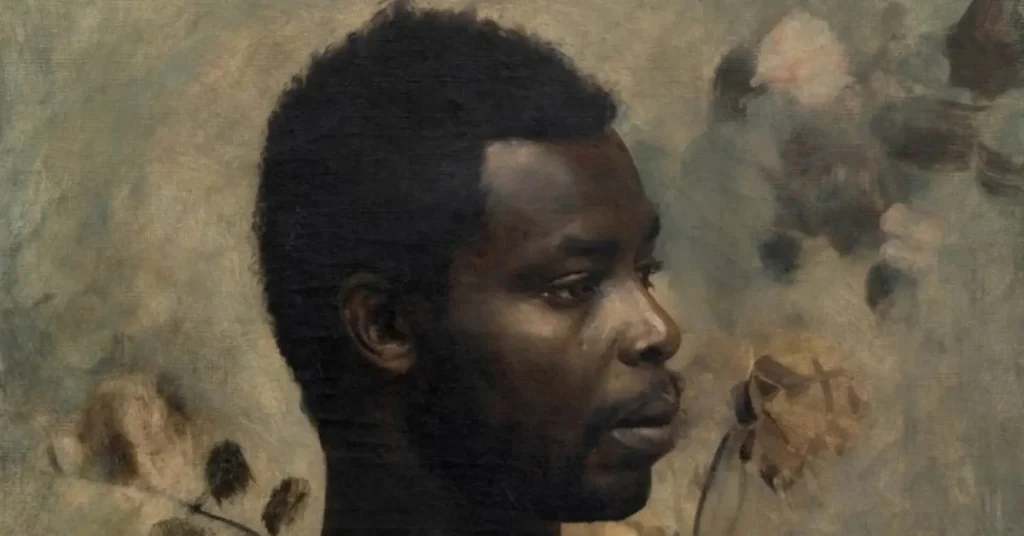

The Painting: Klimt’s Only Known Portrait of an African Prince

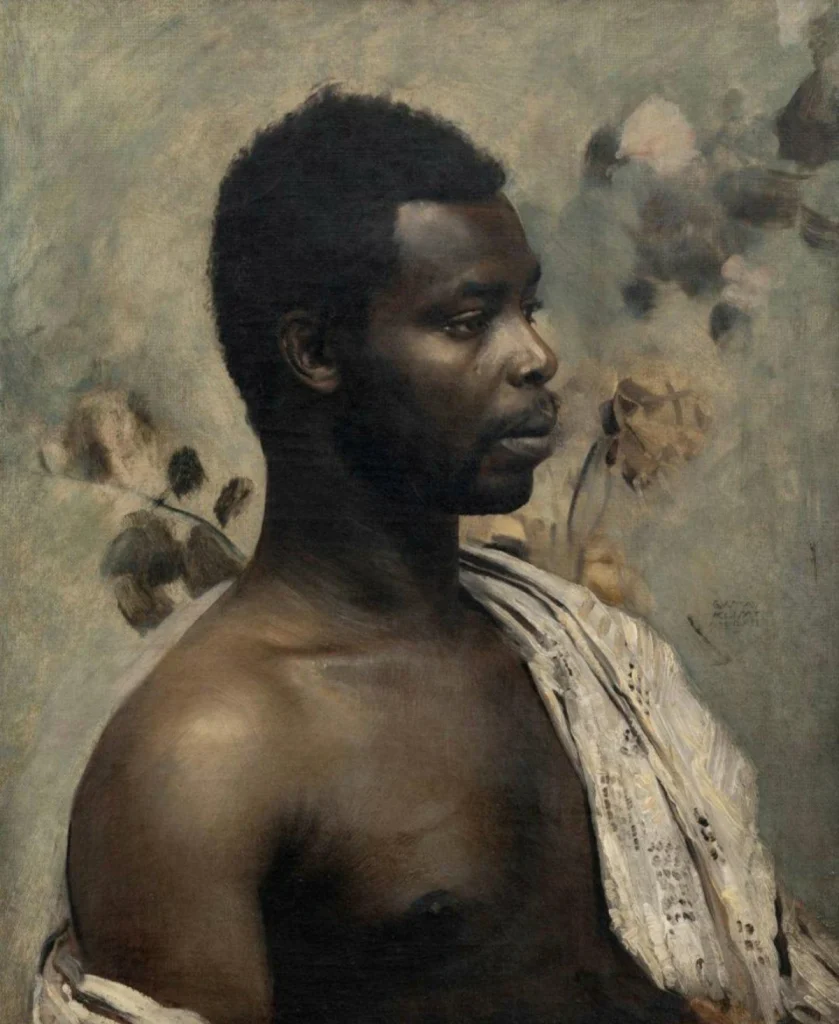

Prince William Nii Nortey Dowuona (1897) is an exceptional painting by Gustav Klimt, made during a pivotal year when the artist co-founded the Vienna Secession movement. The two-foot-tall canvas depicts a West African nobleman from the Ga community of present-day Ghana. According to Alfred Weidinger, a renowned Klimt scholar, the portrait “marks the transition to a new stage in his artistic development.”

Courtesy – Reddit

Before the March TEFAF fair, the painting had never been exhibited publicly in modern times, making its appearance all the more significant. Lui Wienerroither, co-founder of Wienerroither and Kohlbacher Gallery, which showed the painting, referred to it as “the only Klimt painting on the market” at the time.

Decades in the Shadows: A Twisted Provenance

The portrait’s modern history begins murkily. It resurfaced in Hungary, where it had reportedly been in private ownership since the 1950s, and was later examined in Budapest at a Painting Examination Laboratory. Hungarian conservator Zsófia Végvári confirmed that the painting bore the Gustav Klimt estate stamp, albeit faint, and also noted the artist’s name hidden under infrared light on the stretcher.

The painting’s trail before this is dotted with gaps. It had last appeared publicly in 1928 at a Vienna Secession memorial exhibition, owned by Ernestine Klein, a Jewish art collector. Ernestine and her husband, Felix Klein, fled Austria in 1938 under the Nazi regime, eventually hiding in Monaco. The painting vanished from the art world thereafter until its recent restitution to Klein’s heirs.

Hungary’s Cultural Heritage Laws and a Potential Breach

At the heart of the controversy is whether the painting was left in Hungary illegally, potentially in violation of national cultural heritage laws. These laws stipulate that artworks over 50 years old and valued above 1 million forints (approx. €2,500) require export approval.

Courtesy – Kronen Zeitung

Hungarian newspaper HVG claims no such permit was issued. However, Austrian daily Der Standard counters this with documentation: an export permit dated July 21, 2023, was indeed issued by the Austrian Federal Monuments Office, which claims to have received the necessary clearance from Hungary. A gallery representative told ARTnews, “The painting was inspected by Hungarian authorities and declared safe. This authorised its export.”

A Bureaucratic Oversight?

Multiple reports suggest that Hungarian officials may have overlooked the Klimt estate stamp, mistakenly believing the painting was not particularly valuable. According to Der Standard, Hungarian authorities failed to recognise the painting’s significance and allowed it to be exported without a proper assessment.

Zsófia Végvári, who conducted the technical analysis of the painting, wrote in her blog that “the estate stamp is present, though faint,” and pointed to subtle identifiers only visible with advanced techniques.

Hungarian cultural historian Péter Molnos, author of Lost Heritage, took to Facebook, questioning: “Have we lost a Klimt?!” He labelled media coverage as “seriously movie-like,” hinting at the almost cinematic twists in the painting’s journey.

A Restitution Case Under the Washington Principles

Wienerroither and Kohlbacher assert that since the painting was returned to the heirs of a Jewish Holocaust-era collector, its export should fall under the Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art, which Hungary has signed. The gallery emphasised, “Since this is a restitution case, the painting falls under the Washington Principles… which would have resulted in its export from Hungary.”

Courtesy – Daily Dose of Art

However, no official statement has been made by Hungarian authorities affirming or denying this claim in the context of the Washington Principles.

TEFAF and the Future of the Painting

Though its appearance at TEFAF Maastricht garnered significant media attention, it remains unclear whether the painting has been sold. Gallery co-founder Wienerroither mentioned “active negotiations with a major museum,” but no acquisition has yet been publicly confirmed. Given the painting’s historic, artistic, and political significance, its future ownership and final destination may depend as much on legal clarity as on curatorial interest.

A Masterpiece, a Mystery, and a Moral Question

The saga of Klimt’s portrait of Prince William Nii Nortey Dowuona raises profound questions about art restitution, cultural patrimony, and bureaucratic accountability. While the painting has finally emerged from obscurity, its journey is far from over. As debate rages on between Hungarian and Austrian voices, and with provenance experts and legal analysts weighing in, the world watches to see where this rediscovered masterpiece will finally rest.

Image – Gustav Klimt. Prince William Nii Nortey Dowuona (1897), Oil on canvas (detail). Courtesy – All That’s Interesting

Contributor