Ancient Foundations: Urban Planning and Craftsmanship

Design in India has evolved through a long, layered history where craft, technology, and ideology constantly intersect. From ancient urban planning to contemporary digital interfaces, Indian design has negotiated between tradition and modernity, utility and symbolism, local forms and global influences.

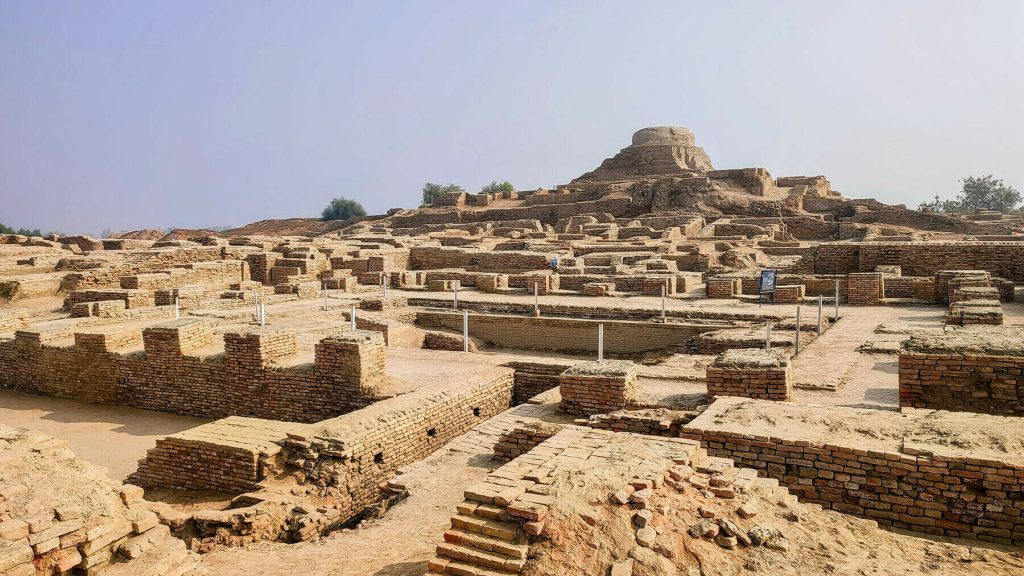

The earliest evidence of design consciousness in India appears in the Indus Valley Civilization, around 2600–1900 BCE. Planned cities such as Mohenjo-daro and Harappa reveal sophisticated urban design: grid-pattern streets, standardized brick sizes, drainage systems, and public baths. Everyday objects—beads, seals, pottery—show refined sense of proportion, abstraction, and symbolism. Here, design is inseparable from craft and urban governance, embedded in the rhythms of daily life rather than separated as a distinct profession.

Janpadas: Architecture, Textiles, and Regionality

In the subsequent centuries, design flourished through architecture, textiles, metalwork, and ritual objects. Mauryan and Gupta periods saw the emergence of iconic design vocabularies in pillars, stupas, and carved reliefs, where structural clarity met symbolic narrative. Temple architecture across regions—Nagara in the north, Dravida in the south, Vesara in the Deccan—developed complex systems of form, ornament, and spatial sequencing. Simultaneously, textile traditions such as block printing, weaving, and dyeing (from Banarasi brocades to Kanchipuram silks) established India’s reputation for surface design and material innovation.

The medieval period introduced strong Islamic influences through the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire. Mughal design synthesized Persian, Central Asian, and Indian elements in architecture, gardens, manuscripts, and objects. The charbagh garden, inlay work, calligraphy, and geometric patterns reflected a holistic visual system that extended from monumental buildings to carpets and jewelry. Design here became a marker of imperial identity and aesthetic power, even as artisanal guilds continued to develop regionally distinctive styles.

Colonial Times: Tradition Versus Industrial Modernity

Colonial rule radically reconfigured India’s design landscape. British industrial products, new materials, and printing technologies entered the market, while colonial institutions categorized Indian crafts as “traditional” and often subordinate to European taste. At the same time, Indian textiles and decorative arts were displayed in international exhibitions, reframing them as “oriental” design for global consumers. The rise of art schools in Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras introduced academic realism and European design principles, but also inadvertently created a space for critical reflection.

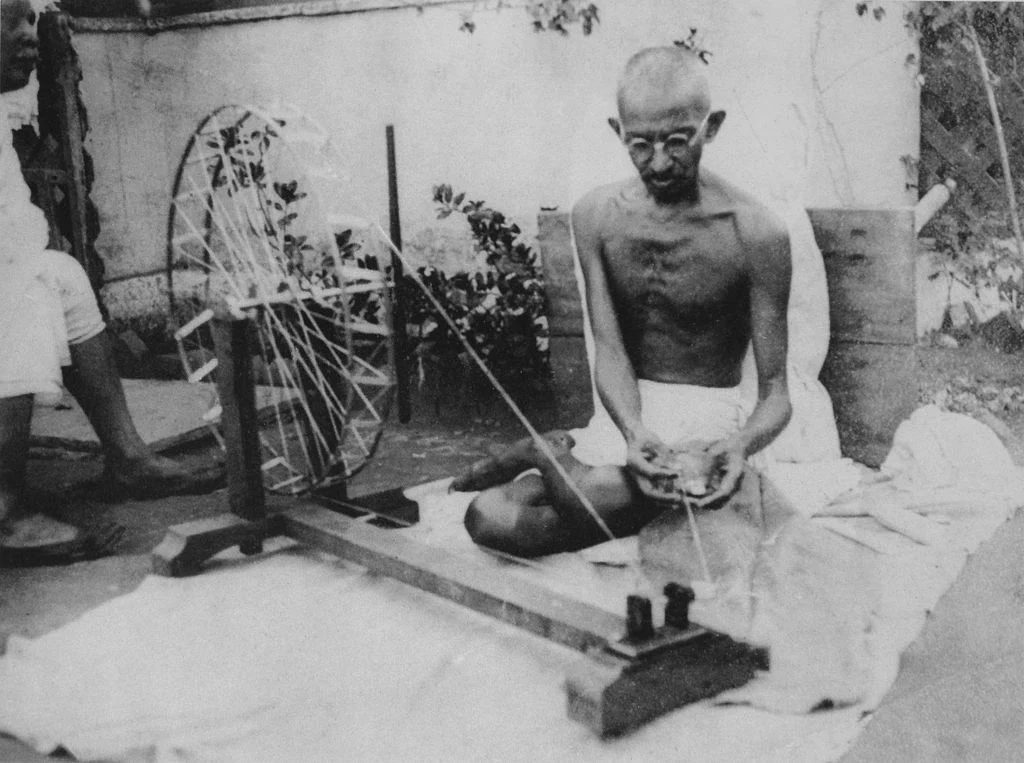

Design as Resistance: Nationalism and Independence

In the early twentieth century, design became entangled with nationalism. Leaders of the freedom movement, especially Mahatma Gandhi, foregrounded khadi and hand-spinning as symbols of self-reliance and resistance to industrial colonial goods. This transformed an everyday fabric into a powerful design object loaded with political meaning. Parallel to this, figures like Rabindranath Tagore and Nandalal Bose explored ways to modernize Indian visual language without abandoning indigenous forms, setting the stage for later design debates.

Institutionalizing Design: The Post-Independence Vision

After independence in 1947, the newly formed nation-state recognized design as central to development and modernization. The establishment of the National Institute of Design (NID) in Ahmedabad in 1961, inspired by the Bauhaus and Ulm School, marked a turning point. NID’s founding vision, articulated in the “India Report” by Charles and Ray Eames, argued that design in India must address real social needs, bridging craft traditions with industrial production. This period saw the emergence of industrial design, graphic design, and exhibition design in more formalized ways, often connected to public sector enterprises and national campaigns.

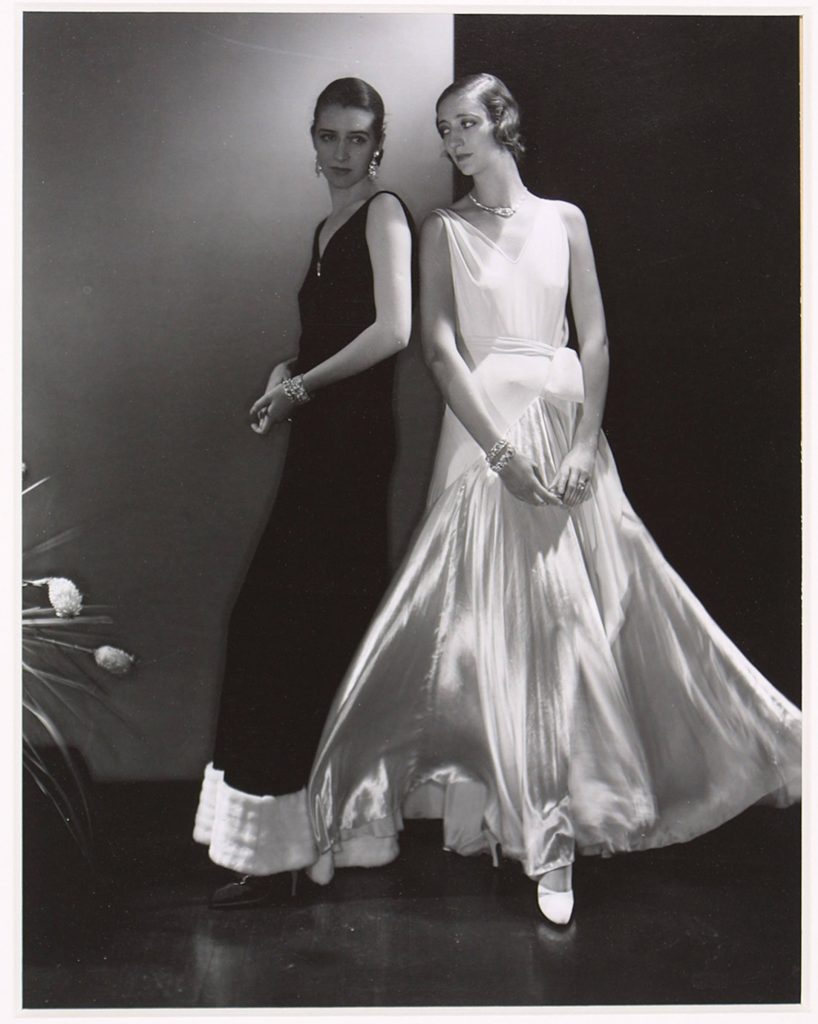

Consumer Markets and Cultural Identity: Design in Transition

From the 1970s onward, Indian design gradually moved beyond state-led projects into consumer industries such as automobiles, appliances, packaging, and branding. Television, advertising, and later liberalization in the 1990s opened up markets and created demand for visual identities, product differentiation, and user experience. Fashion design emerged as a distinct field, with designers reinterpreting traditional textiles and silhouettes for urban and global audiences. This era was marked by negotiation: embracing global design languages while asserting “Indianness” through motifs, materials, and storytelling.

The Digital Era: From Interfaces to Inclusive Innovation

The digital turn of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries expanded the definition of design further. Interface design, interaction design, and service design grew alongside India’s IT and startup ecosystems. Designers began to work on mobile apps, financial inclusion tools, healthcare services, and educational platforms, often focusing on frugal innovation and inclusive design for diverse user groups. Design thinking entered management, social innovation, and governance, reframing design as a method of problem solving rather than only form-giving.

Contemporary Intersections: Tradition Meets Tomorrow

Today, the history of design in India is understood as both a continuity and a series of ruptures. Ancient craft lineages coexist with AI-driven interfaces, handloom clusters collaborate with luxury brands, and grassroots social enterprises sit alongside multinational consultancies.

Athmaja Biju is the Editor at Abir Pothi. She is a Translator and Writer working on Visual Culture.