…That’s why it’s worth a read

Ever since I was a boy, I would bicycle around my little town, Tezpur, with my watercolour pack and cheap papers, looking for subjects that would make thrilling landscapes. Cole Park was my favourite muse. It is dotted with various types of foliage, a large pond and a stone structure that is historically significant. It showcases the things that are good about Assam.

After every watercolour landscape, I began to understand that my ambition was inversely proportional to the quality of the picture I made. If I decided to paint a place, I realised I had to edit out some portions of the view to serve my painting better. I would knock off trees or other structures that made my life difficult, and paint to my strength. Simplicity was the first principle of art that I learnt on my own. Too much was too bad. One boat on the Brahmaputra was much better than painting a Spanish flotilla. Not everyone can paint a crowd, and one’s primary inclinations decide what your subject will be. I have an unusual distrust for the mob and its celebration and so, in keeping with my primary nature, I decided to talk about that which is a part of a quieter history.

Since that first little understanding of the value of editing and simplicity, I have come to understand a few more things. I must warn you this may not be a pleasant experience.

I cannot count how many times I have heard this line: Everyone is an artist in their own way.

This view is poetic and refreshing. It believes in a beautiful world, where everyone attempts to transcend their insignificance by infusing something bigger than themselves to the most routine tasks in life. For instance, I love to believe that airport luggage handlers enjoy how a suitcase feels. They probably even wonder what beautiful secrets it holds within. I want to believe they tend to the suitcases with care and consideration, like a poet trying to find the right word. Except that’s almost universally untrue. Less than a countable number of people probably are like Hirayama in Perfect Days, who cleans a toilet like his life depended on it – as if it were a genocide of germs to be carried out with clinical precision. Despite possible lawsuits hanging in the air, luggage handlers practise a common variety of S&M while attending to the million suitcases that fly in daily. In short, your suitcase is a survivor of the mechanical cruelty of most handlers tied down by a mechanical system that chokes creativity. To understand it, you can think of Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times.

This is also true about the “everyone is an artist in their own way” statement. You might even say everyone is a luggage handler in their own way, and far from an artist.

Everyone is not an artist in any way and most people are unlikely to be artistic ever. The system does not allow it. Thinking and acting artistically is a rare event. Even artists are not artistic all the time. It is a rare event even for those who are resolute professionals. In fact, an artist has to overcome his need to be unartistic in order to make something that ascends to a plane of sublimity, something that resides beyond the crudity of business. Worst of all, most folks cannot be remotely artistic without some politics or cause to fall back on. When your slate is wiped clean of opinions and politics, art becomes really very difficult. The reason is simple: now you have to make something intrinsically human, beyond the facade of ideology. A rose looks different when seen through the lens of different ideologies or cultures, but to a human it is just another flower, as pretty as any other flower.

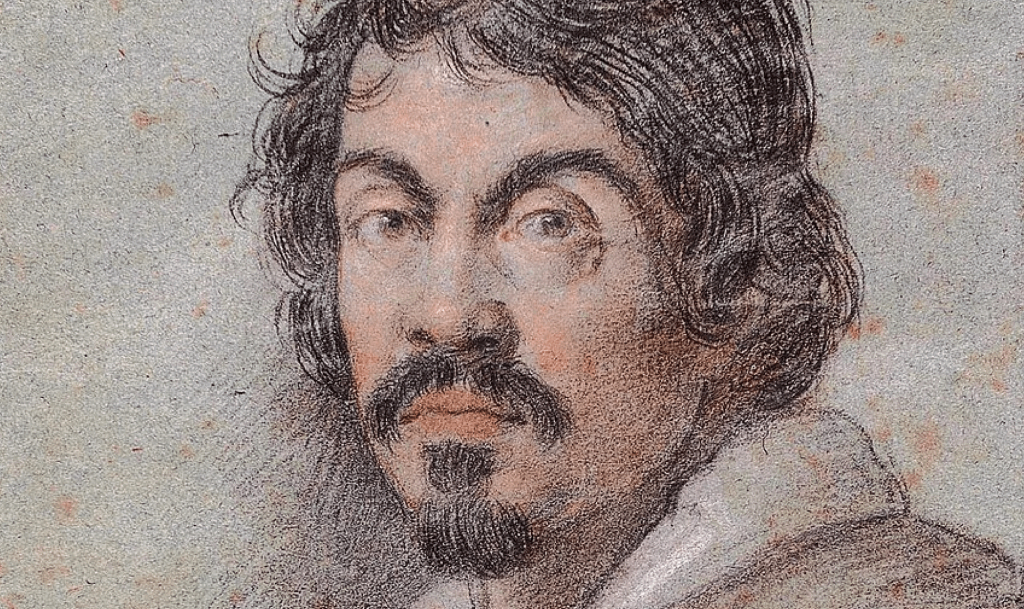

Not all artists are great human beings, and it is a corollary of “not everyone is an artist in their own way”. In fact, every artist might be a criminal in their own way. If you do not agree with me, look at Caravaggio. He murdered somebody. Today, we eulogise his art as a moment in history when skill kept up with ideas. An artist’s job is not to tell you a greater moral truth. It is simply to tell you a greater truth. And that itself is a way of understanding the human being from a place of an amoral affinity for life. It definitely is weird and not your average dinner time conversation.

Sometimes, the greatest artist behaves like a common brute. If you are looking for an example, you don’t have to go further than Picasso or John Lennon. While Picasso was a seasoned psychological manipulator (a probable narcissist driving his partners crazy), Lennon was not averse to throwing a punch at his wife. A great artist can also be a great abuser, even as he entreats you to imagine a utopian world. Being an artist in the “real way” and not in “your own way” might even come with grave moral depravity. Worst of all, it could come with a garden variety of clinical insanity. Now, think of it this way: what do you want to be – a human or an artist? It’s a trick question, yes.

In order to understand that everyone is not an artist, one requires humility and a commitment to calling a spade a spade. While the ritualistic nature of a Japanese tea ceremony may elevate it to something culturally significant, every tea-seller cannot achieve this elevation for two main reasons: it is a common activity and it works on volume. Neither would you have the patience to wait if a tea-seller at a railway station performed a long and ancient-looking ritual before giving you a cup. Nobody wants to miss their train. That tea-seller is not an artist, nor are you an artistic tea-drinker. This is as mundane as common can hope to be. This scene can only become art if a person intentionally turns it into a painting or a poem or a song, keeping in mind the structural and imaginative qualities art requires. Which is why Cezzanne’s card players are nothing like your average card players in a bar.

If somebody tells you they are an artist, you can be almost sure they aren’t. A true artist is ashamed of this moniker. It takes a serious artist many years before accepting that they are an artist. The reason is simple: when you start out becoming an artist you have no idea what art is, and this ignorance continues till your death. It is debilitating to make art without coming close to understanding what makes art, art. It simply means art is not always joyful, but a method of not letting the fluff win over the real stuff.

A true artist is constantly swinging between inspired restlessness and a depressive urge to quit. They have an “inkling” at best. They know bad art when they see it. And a truly great artist is unsure even when she or he sees bad art. The amount of humility that goes into not knowing what art is, is an introductory step in understanding what art might be. Art is not something that happens to you when you feel like it. You have to align every one of your instincts to the idea that something beyond the human experience of beauty is possible to freeze in time or memory. Maybe then you might get an insight into the fact that becoming an artist is difficult.

An artist has no logical or tangible roadmap. She or he has to chart their own course. And that my friend is incredibly isolating and tough. Which is why, though art schools churn out art graduates by the dozen, often the bad student, the dropout, the reject or the rank outsider appear to have more authentic ideas. Success does not guarantee artistic merit.

We find great solace when we are acclimating to our dreams because nightmares precede it. For an artist to finally become an artist, it requires many failed experiences. An artist who has never failed in his endeavours is to be looked at with some suspicion, if not disdain.

Many artists make derivative drivel because somebody had the audacity to say that regular artists copy and great artists steal. That was Picasso’s smart alecky quotable quote. If you ask me, great artists do not steal. Picasso just wanted to sound cool is all. For example, where do you think Picasso stole the Guernica from? You could say African art, but the fact is that Picasso is as African as a giraffe is a llama.

An artist that steals is lazy. An artist that makes art he stole from others into a refashioned trope, is not just a thief. He is tired. Since creativity is not a codified system, how you engage with creative work is not important. The idea is to do what could have been done before, only better. A great artist doesn’t steal. He cannibalises, and turns it into an act that is both novel and universal. Picasso’s African faces are his own, though a little African mask did cross his path. It does not belong to Africa. He is original because he chooses to turn the usually seen into a usually unseen object.

If you ever see the work of an artist that looks exactly like somebody else’s work, you can simply say this: now that’s a thief. You can’t just be that person who identifies as an artist one fine morning. And, in fact, you would wish you were a cannibal, devouring art from the present time and turning it into a newer idea of taste. An artist that copies is merely a character actor in the grand drama of life. So, look for the cannibal, not the thief. Or, probably, the sorcerer who can hypnotise you.

There are those that believe that making an effort to be an artist is artistic enough. Nothing could be farther from the truth. If you are trying to be an artist, you are definitely not one. Artists are rarely made. They are almost always born, and only a select few become one. And I am not talking about fame here, because fame can be made but an artist cannot be made. There are so many slovenly pretenders made by fame. For example, Cy Twombly. He made quite a few poor paintings but somehow he made fame better. And it is always with the help of a few curators who think they are the gatekeepers of art. I even read somewhere that it is more interesting to “think about Twombly’s art than actually see it”. In any case, this is a debate for another day.

Whenever you wish to make a mythology of bad art, you need curators who know words like ‘liminal’. Quite often great artists are made by curators who are bored because they wish to use their thesaurus somewhere. They tell you why a piece of bad art is good and you have to agree because there is no way you can fight the semantic missiles of someone who went to college and learnt some nice words. History is witness to the fact that many of the greatest artists were who they were despite the curators and the so called cognoscenti. I won’t give examples because it is pointless to say stuff like, it took Vermeer 300 years to be discovered or that Janet Sobel was the true Jack the Dripper, and not Pollock.

Another common statement we hear is, anybody can learn to be an artist. The answer is almost always no, and sometimes yes. Paul Gauguin gave up being a stockbroker at 27 to pursue art. But he also had teachers like Pissaro. But before that he painted more than occasionally.

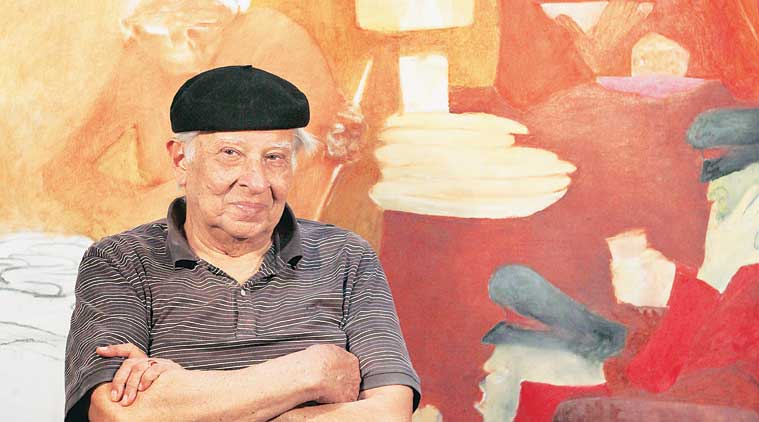

Krishen Khanna stopped being a banker to paint full time, but it took a while to get there. His friends were guys like M F Husain. And Homi Bhabha buying his first work, is a testament to his natural talent and his tenacity when it came to making art. These guys were not just learning to be artist. They gave up everything to paint. They were drawn to art by circumstances that can only be coped with an act that has profound intrinsic value. To make art is to feel the same attraction that you feel for an unattainable lover.

Yes, you can become an artist later in life. Janet Sobel did that. So, did Van Gogh and many others who are not really famous. But you can bet your last morsel of food that they chose art because nothing else could have allowed them to touch that sacred spot, where you begin to stop thinking and start living.

What this essentially means is that, you cannot simply go about life saying that you are an artist because everyone is one in their own way. That is delusion. You have to cut your safety net and plunge head first into uncertainty if you wish to, at least, get a whiff of the wonderful. In short, while this is not a motivational piece about art, it wishes to help you wake up and smell the coffee. Everyone can make art that is strong, that is brave, that is true, provided you are willing to understand that it is a lot of work and not something you can feel or identify with. You just have to put in the hours and probably lose the life that was your comfort zone. You have to find the artist you were born as. And it takes a long time. That’s the beauty of it.

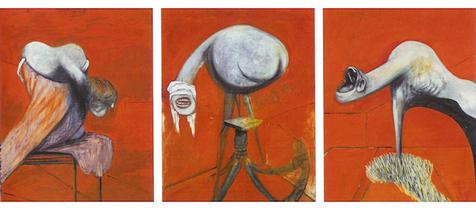

Cover image: Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, 94 × 74 cm (ea), Tate Britain, London

Former Editor at Abir Pothi