Birender Yadav’s ‘Only the Earth Knows the Labour’ (2025), which is exhibited at the Muziris Biennale in Kochi, deserves special attention in the context of the ideas it puts forward. The marginalisation of migrant workers is a significant subject in Yadav’s 2025 work. Yadav focuses on the “facelessness” of those who construct our contemporary infrastructure within the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, which frequently examines topics of migration and trade. Birender Yadav’s theme, which explores the lives and toils of labourers who work hard, even in the hardest seasons, also raises questions about the workplace and its representations. Yadav, whose practice is deeply rooted in his upbringing as the son of a blacksmith in an iron mine, uses this installation to bridge the gap between industrial raw materials and the human bodies that extract them.

Birendra Yadav primarily highlights the life experiences of migrant workers. Beyond the realities that the workplaces at the lower levels are extremely unsafe, the work life of migrant workers is even harsher. While many are forced into migration because they are already vulnerable, the truth is that migration makes them even more vulnerable. This is the reasoning Birendra gives for prioritising migrant workers’ lives.

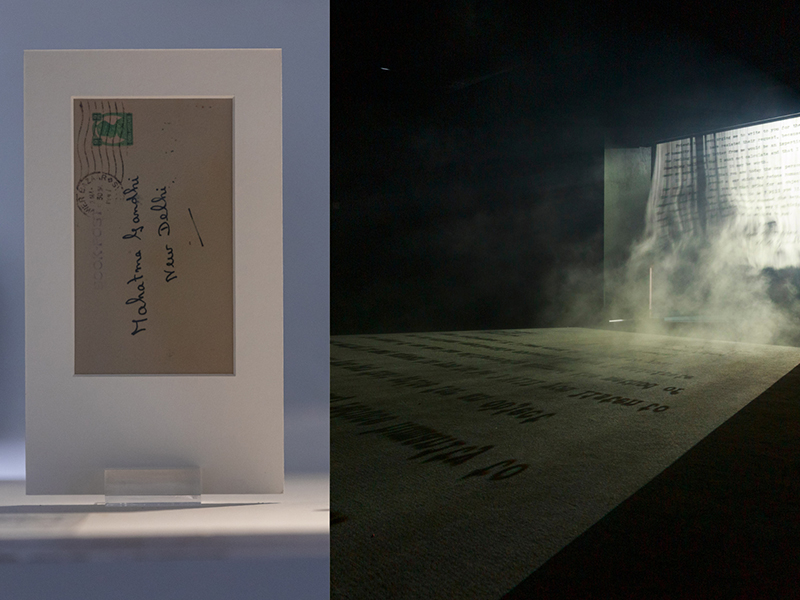

The installation is characterised by its use of industrial and terrestrial materials—iron, earth, and coal. However, these materials are not intended for their conventional meanings; instead, they are prepared to suit the artist’s own logic. Yadav’s choice of materials is never arbitrary; they represent the weight of the “resource curse” and the physical toll of manual labour. The work frequently blurs the distinction between the tool and the hand. Tools are shown in Only the Earth Knows the Labour as extensions of the labourer’s exhausted body rather than as proper equipment. The installation has the atmosphere of an excavation site. It views modern labour as a historical cycle of exploitation that remains hidden, rather than as a present-day success story.

Birendra’s contribution to the Biennale signifies a shift in Indian contemporary art toward a more sympathetic socio-political realism. Instead of focusing on the abstract, he challenges the viewer’s involvement in the labour economy by utilising the “dirt” of reality. Since this work states it is a labour economy, it should be presumed that this artwork is considered explicitly in that context. Theoretical readings about the labour economy are relevant here. This work depicts the lives and working conditions of the largely powerless bonded labourers trapped in exploitation and socio-economic inequalities in the brick kilns of Uttar Pradesh. However, when entering the exhibition space of this artwork, it feels like stepping into a meticulously arranged place of ritualistic practice; it is evident that this carefully prepared installation communicates much without overtly saying it. To understand exactly what it conveys, one has to go through it attentively, engaging with each element and each object.

This installation by Birendra provides an opportunity not just to engage through visual perception, but also to experience firsthand, as you move through the realm of art arranged in an orderly manner. Karl Marx said that ‘Art is always and everywhere the secret confession,’ and at the same time, it is the immortal movement of its time. While it is a secret and a worship, when we say ‘immortal movement of its time,’ Marx meant that the progress art promotes should be understood as a forward movement that can never perish. An atmosphere without workers is being created here. However, it is through the presence of bodies whose connection to workers is unclear—such as a headless body, a body tied to a wall, or a body lying down—that the interior of workplaces is being constructed. The workers, the objects made through their labour, are the main objects of the exhibition. Additionally, by showing that this workplace is also filled with the materials required to create these objects and that it is a centre of exploitation, the artist is creating a critical space.

While working in the brick kiln, the presence of numerous clay-made products connects this work to other labour worlds as well. The linear images are communicating with us through the constructions surrounding the stove and the objects arranged within it. Their absence becomes a presence through the contours and planes of the forms we like. The season for preferred stoves is from November to June. The period before that is for labour, and once the season ends, it marks a period of income loss and idleness. It is between these two periods that the lives of the workers are shaped. After the season ends, workers’ homes are demolished, and stoves are taken away. Orphaned items from this process are displayed in the work. These items simultaneously bear the loneliness of abandonment and the burden of labour.

As the stoves and dwellings are sealed off, both the people and the areas are rendered orphaned at the same time. Their void is being filled, and in the absence of those who once protected these places, darkness fills them. At the same time, their handprints are imprinted on every brick, which, while being the handprints of labour, are also the handprints of exploitation. These marks, like handprints, also bind the bodies together. The daily objects transform this artwork into something with multiple layers, scattered like indirect traces of life stories. In these sculptures recreated as castings, one can see various jars, cloth bundles, tools, clothes, and more. While each of these tells a story, it remains silent. They are not quiet because they lack stories. Every piece of clothing preserves a slight variation created by the worker who once used it. In each, a person’s absence casts a shadow.

Three things are evident in this installation: the first is the worker’s body, the second is their labour, and the third is the earth they handle. It is when these three come together that the actual movement of the world we live in takes place. The worker’s labour is what is manifested here. However, there is also the reality that it passes through exploitation.

Contributor