Art fairs have a long and fascinating history, originating from the fusion of commerce and religious festivities in ancient civilizations such as the Roman, Greek, Aztec, Inca, and Han empires. These festivals, organised by the ruling elite, served to reinforce their power and attract vast populations from diverse regions. Over time, religious festivals evolved into artisanal fairs, providing platforms for trade and the exchange of rare goods. The development of art dealers further transformed the dynamics of these fairs, acting as intermediaries and expanding the reach of the art market. Today, contemporary art fairs build upon this rich historical background, adapting to the demands of the global art market and serving as vibrant hubs for sales, collaboration, and artistic expression. In this essay, we will explore the significance of art fairs in the global art market, their evolution over time, and the institutional features that have contributed to their success. We will be looking into their historical roots, from religious festivals to artisanal fairs, and examine how contemporary art fairs have implemented and built upon these previous developments. By examining the network-based structure of art fairs and their impact on local markets and collaborations with other industries, we aim to shed light on the enduring influence of these dynamic events in the art world.

From Religious Festivals to Contemporary Art Fairs

Fairs, as we know them today, can trace their origins back to religious festivals and gatherings that combined commerce with religious activities. These festivals were prevalent in ancient civilisations such as the Roman, Greek, Aztec, Inca, and Han empires. The ruling elite used these events to reinforce their exceptional qualities and solidify their power.

In ancient times, religious festivals were held on specific days of the year and were often associated with seasons or the name days of specific gods. These festivals existed in nearly all major ancient empires and were characterised by strong social differentiation and the division of labour. Within these civilisations, clerical castes began to emerge, and hierarchical organisation came to dominate social structures.

The significance of these annual religious festivals lay in their ability to gather vast populations in one location, serving to confirm the exceptional nature of the ruling elite. Organising such festivals required the interruption or cessation of daily activities for the population, with people from different regions, tribes, and social strata converging in a single place. This necessitated the establishment of a transportation system, including safe roads, which could only be ensured by a powerful ruling elite.

Moreover, to attract a large number of people, the festivals had to be visually appealing and captivating. Additionally, the attendees needed to be fed and provided for during the events. As a result, the festivals tapped into networks in several ways. They reached out across the empire, creating a small-world network that brought together people from distant regions. This network allowed the ruling elite to educate and inform the attendees about norms and rules while simultaneously presenting themselves as god-like figures.

The success of these festivals relied on their ability to temporarily suspend normal norms and rules within the festival space, yet still extend their influence into the territories governed by the ruling elite. This structural model of a small-world network, with its density and temporally formed strong ties, contributed to the festivals’ impact.

The semantic connotations associated with fairs also have their roots in these ancient religious festivals. The term “fair” derives from the Latin feriae, meaning holidays or holy days. It suggests freedom from labour (feriata) and captures the extravagant, festive, and splendid nature of these events. Similarly, the German word for fair, Messe, reflects the religious origins of fairs, as it originally meant religious mass and referred to large-scale religious events. Messe can be traced back to the Latin missa, which also relates to the Greek pompe, signifying a mission or festive procession.

Importantly, the festivals not only attracted people but also resulted in the accumulation of valuable and rare goods in a concentrated geographic area. As a result, these events became associated with trade. Members of the elite attended the festivals to acquire luxury items, which contributed to their social distinction. The infrastructure of ancient kingdoms and empires facilitated the transportation of these rare goods, enabling regular festivals to take place.

This regularity of imports and the knowledge that specific goods would be available on the same festival day of the following year led to the concept of a consistent market. Producers and sellers recognised that fairs provided them with an opportunity to sell certain types of goods. Karl Polanyi has discussed the transformation from gift trade within religious festivals to market trade in fairs, which was a common trend across many ancient civilisations.

The Development of Artisanal Fairs: From Religious Festivals to Commercial Platforms

The development of artisanal fairs played a significant role in the evolution of fairs as a whole. These early fairs were not exclusive to art but emerged as a result of religious festivals. Unlike the frequent religious festivals, artisanal fairs were held annually and in specific locations.

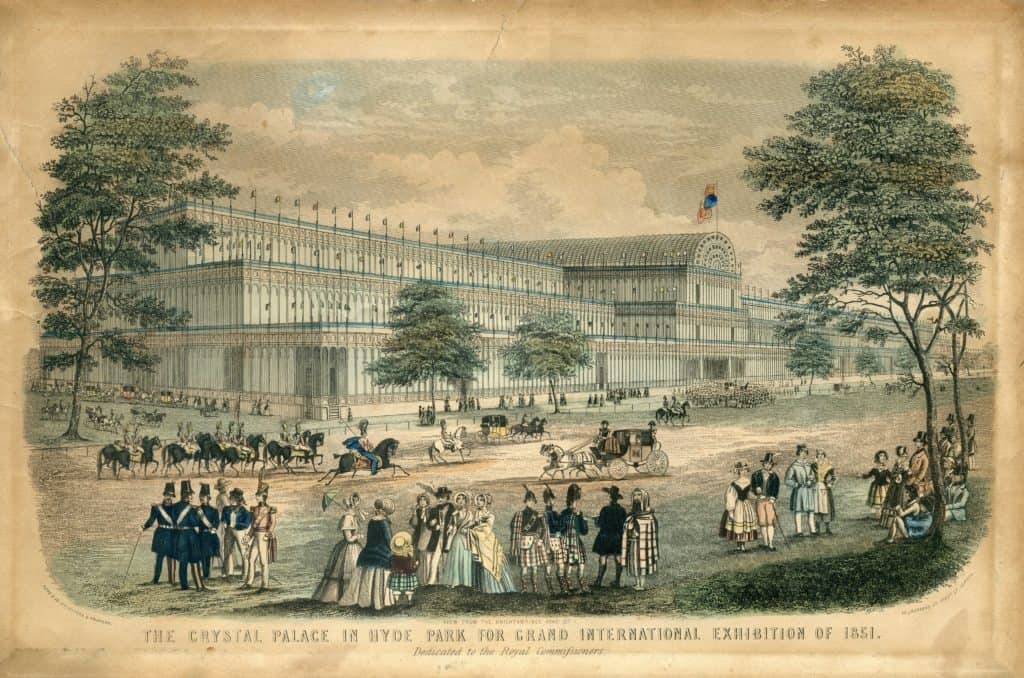

One of the earliest and most important examples of artisanal fairs was established near Paris at Saint-Denis during the rise of the Frankish Kingdom in the late 7th century. From there, the concept of artisanal fairs spread to the Champagne and Flanders regions in the 12th and 14th centuries, respectively. The Champagne fairs, in particular, became crucial for the development of economic practices within artisanal fairs. The fair business extended to cities like Geneva and Lyon until the religious wars in France in the 16th century. Subsequently, the golden age of fairs emerged in Germany and England. However, in the 18th century, fairs went into decline, while new fairs emerged in Russia, further east, connecting Europe and Asia. The Russian fairs eventually ceased in the late 19th century.

Courtesy: Ancient History Encyclopedia.

Artisanal fairs differed from religious festivals in that their focus shifted from the sacred to the commercial. These fairs provided platforms for sales, the formation of prices, creation of transactions, and the trading of rare items. They built upon the previous structural features of festivals, such as the gathering of people and goods from distant lands for exchange. However, the artisanal fair introduced new structural elements. Rather than transmitting religious or political messages, it emphasised mutual observation.

Economic integration and the formation of prices were key aspects of artisanal fairs. The fairs in Champagne, for instance, were strategically located at major caravan route intersections, and the nobles of the region implemented protective systems for merchants traveling to and conducting business at the fairs. The “conduct of fairs” ensured the safe arrival of merchants from distant lands, while the “ward of fairs” protected trade within the fair, guaranteeing contract fullfilment and security for attendees and goods. The international nature of these fairs necessitated financial systems for credit and money clearing, ensuring that transactions conducted within the fair had an impact beyond its immediate setting.

Artisanal fairs became central institutions in premodern economies, which relied on household subsistence and patron-client relationships. These fairs allowed for economic surplus and profit with regard to scarce items. The network-like structure of the fairs facilitated the formation of prices through mutual observation. Rather than being based solely on demand, prices were determined by comparing similar goods presented at the fair.

The spatial organisation and aesthetic appeal of artisanal fairs also played a significant role. The fairs were arranged in rows or streets, with different industries and products grouped together. The arrangement allowed for easy comparison of similar products. Booths and tents were erected specifically for the fair, with some booths resembling vast warehouses piled high with goods. The visual display and clustering of similar industries enhanced the quality and appeal of the goods, giving the fair a sense of glamour and grandeur.

The Emergence of Art Dealers at Artisanal Fairs: Transforming the Buyer-Seller Relationship

During the early days of fairs, the buyer-seller relationship was usually direct, with those bringing goods to the fair also owning them. However, in the 16th century, a significant shift occurred in Antwerp and at early book fairs. Antwerp had become a thriving trade centre, attracting foreign merchants and establishing itself as a hub for international commerce. The city’s commercial infrastructure and skilled workforce provided an ideal market for art professionals.

In this setting, the concept of dealers and their shops, known as Schilderpanden or painters’ halls, emerged. These shops were initially central sales platforms operated by religious institutions. However, as new forms of commercialisation took over, the Schilderpanden became associated with artisanal fairs. Art dealers had the opportunity to lease booths from fair organisers, such as the civic government of Antwerp. This allowed art dealers to come together, forming a collection of dealers aimed at attracting local and international clientele. The role of the art dealer became crucial as they acted as brokers, bridging the gap between sellers and buyers. They facilitated sales by providing external funding and building networks of friends, family, and professionals.

The art dealers possessed the necessary education, social capital, and resources to organise and establish connections with buyers and artisans from different countries. They played a vital role in facilitating sales in distant regions. The formation of these dealer networks enabled the expansion of the art market and increased the reach and impact of the fairs.

Art fairs have a rich historical background rooted in the intersection of commerce and religious festivals. From ancient civilisations to the development of artisanal fairs and the rise of contemporary art fairs, these events have evolved and transformed over time. The small-world network structure of religious festivals allowed for the gathering of people and goods, establishing a sense of unity and providing a platform for the ruling elite to showcase their power. As religious festivals gradually incorporated trade, fairs became associated with the exchange of rare and valuable items.

The emergence of artisanal fairs marked a significant shift towards a commercial focus. These fairs created economic integration, facilitated the formation of prices, and played a vital role in premodern economies. The spatial organisation and aesthetic appeal of artisanal fairs enhanced the display and sale of goods, attracting buyers and creating an atmosphere of grandeur.

Furthermore, the development of art dealers within the context of artisanal fairs brought a new dynamic to the buyer-seller relationship. Art dealers acted as intermediaries, connecting sellers and buyers, and expanding the reach of the art market. Their establishment of networks and their ability to provide funding contributed to the success of the fairs and the growth of the art industry.

Contemporary art fairs have built upon these historical foundations, implementing previous developments and adapting to the demands of the global art market. These fairs continue to serve as platforms for sales, collaboration, and the promotion of artistic expression. They bring together artists, collectors, curators, and enthusiasts from around the world, creating opportunities for networking, discovery, and the exchange of idea.

Conclusion

Art fairs have a rich historical background rooted in the intersection of commerce and religious festivals. From ancient civilisations to the development of artisanal fairs and the rise of contemporary art fairs, these events have evolved and transformed over time.Art fairs have evolved from their religious and artisanal origins to become integral components of the art market. They reflect the interconnectedness of societies, economies, and cultures, fostering the exchange of creativity, innovation, and aesthetic experiences. As art fairs continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly play a vital role in shaping the future of the art world.

Source: Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung , 2014, Vol. 39, No. 3 (149), Special Issue: Terrorism, Gender, and History. State of Research, Concepts, Case Studies (2014), pp. 318-336

Contributor