Berthe Morisot was a pioneering Impressionist in the avant garde art world of late-19th-century Paris, placing the female experience at the heart of her work.

Thinking about the French impressionist movement, a few names come to mind- Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley. A name that gets lost among these is that of Berthe Morisot, A radical feminist who redefined the entire impressionist movement by choosing to explore the female experience through her art. The Male dominated Impressionist circles and the social disadvantage that came with being a woman did not affect Morisot’s resolve to make something of herself.

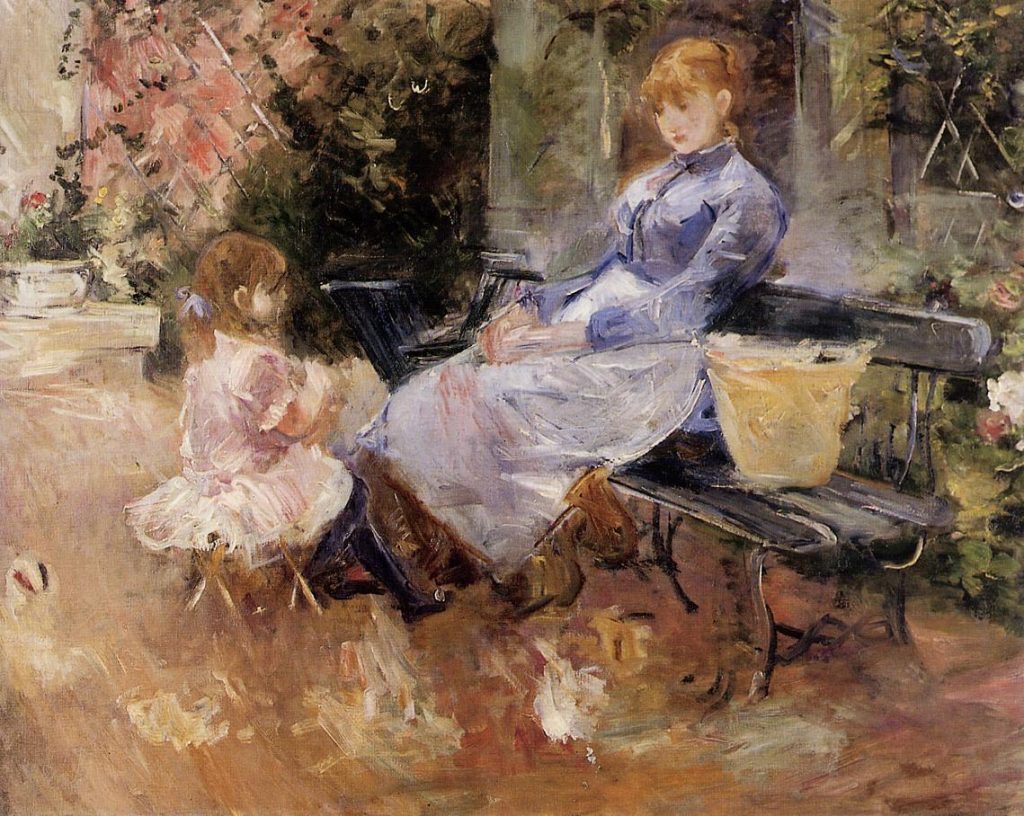

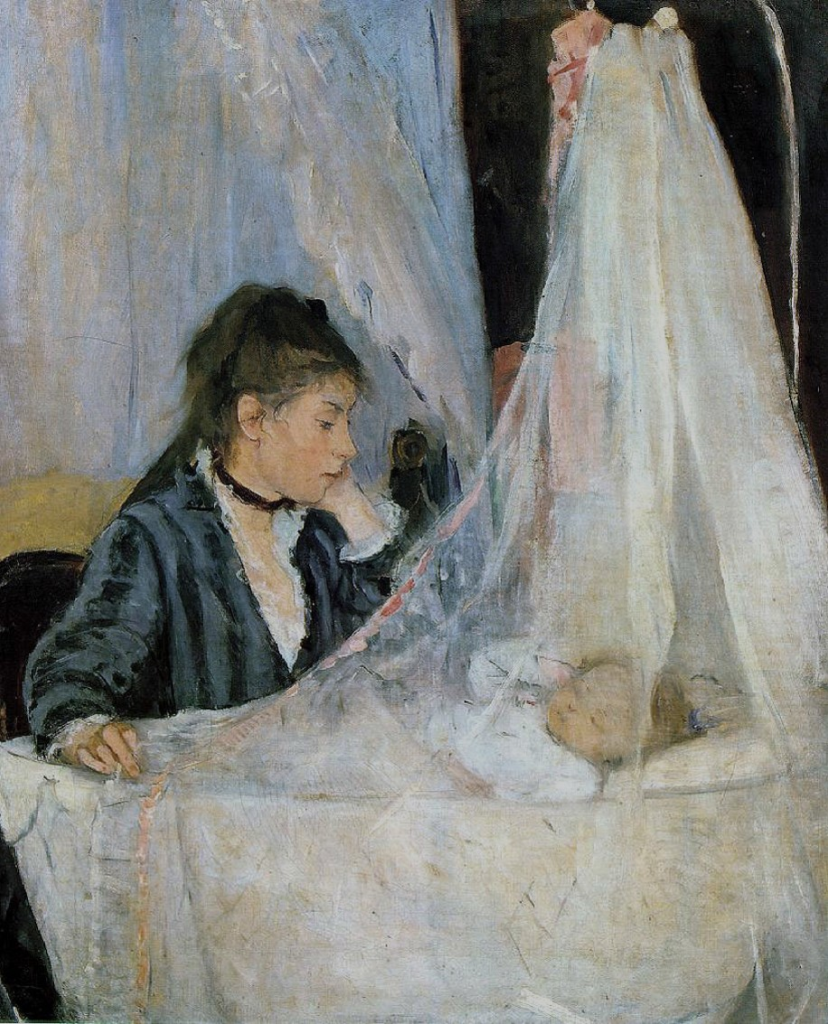

There was an apparent difference in the status of women and men in Morisot’s time that can be noticed in the softness of her art. Her art put domestic life and interiority at its heart. This led to opinions of many critics calling her art “feminine, emotional and domestic”.

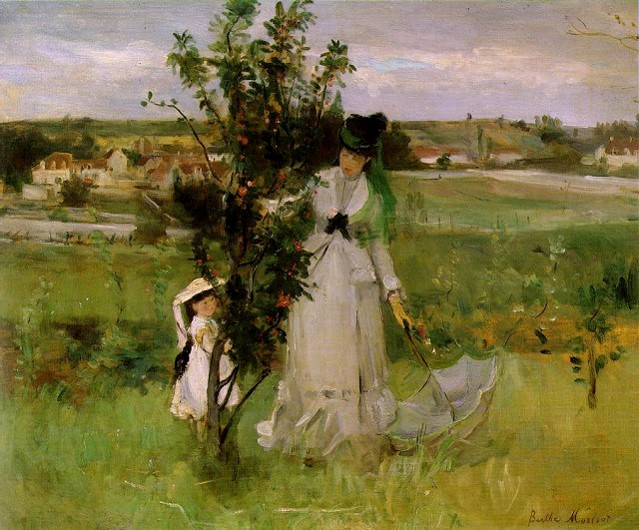

Morisot in her paintings, seeked out subjects that were regarded as second rate by her male contemporaries. She featured maids and domestic servants who were always the staffage figures in other paintings and put them centre stage, in the spotlight, making them the reason for the painting itself. Feeling joy in the process of painting itself, Berthe Morisot challenged the already established idea of what a ‘finished’ painting could look like, leading one journalist to dub her ‘the angel of the incomplete’.

The sidelined status that came with being a female artist in late 19th century Parisian society can be witnessed in the places Morisot chose to depict in her work. While her male contemporaries portrayed the bustling play of life in the city’s bars, restaurants and streets, her status as a respectable middle-class woman shaped her own experience and professional opportunities, determining where and what she was allowed to paint. She looked at her own life, and the experiences of her family and close circle of friends to get inspired instead.

A lot of her work focuses on the mundanity of women’s lives around her. Mothers with their children, pockets of quiet at home or the simple experience of womanhood, embedded in the little things like getting ready. She creates an exclusive world through her art, giving the observer an access to a world exempt from the male gaze.

Morisot’s Woman and her toilette, perfectly captures the modern essence of the mundanity of it all. Keeping in line with the world of female eroticism created by Morisot’s contemporaries, Manet, Renoir and Degas, Morisot picks a different lens. Under the guise of the traditional theme of the ‘toilette’, male artists usually showed women and their bodies undressed, equating getting ready to tantalizing views. She however, uses these subjects to show deep introspection. Shedding light on a Woman’s contentment in her own rich internal world where all the need for performing femininity falls away. Just when Morisot’s semi nudes invite objectifying eyes, Her rough brush work deflects that attempt completely.

Often appearing as absorbed in their own introspection, their attention elsewhere, Morisot’s female protagonists are celebrated for their emotional and psychological depth.

The margins of the morisot’s canvas were often left sparsely painted or even blank, her brushstrokes becoming looser towards the corners, and in some compositions her figures seem to dissolve before our eyes, their bodies appearing almost translucent.

Early Life and Career

Berthe was born into an affluent bourgeois French family with a father working as a government official and her grandfather being the important Rococo painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard.

From early on, Berthe Morisot showed independence in her line of thought. Instead of viewing art as her hobby, as was expected of an upper-middle-class young woman, Morisot and her sister Edma both hoped to be professional artists. They studied under the guidance of Camille Corot, a respected landscape painter who helped them make their public debut at the Paris Salon of 1864 and exposed them to contemporary debates on naturalism and working en plein air. Unlike Edma, who gave up her professional ambitions after marriage to a naval officer, Morisot continued to pursue hers.

Due to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts being closed to female students at the time, the Morisot family sought out private tutors for Berthe and her equally talented older sister, Edma.

Morisot met an eclectic group of fellow artists while studying at the Louvre, including Henri Fantin-Latour, Edgar Degas and Félix Bracquemond, developing a rich network of colleagues and friends as a result. It was Fantin-Latour who introduced Morisot to Edouard Manet in late 1867, sparking an intense connection and artistic dialogue that went on to leave a deep impact on both of them. Morisot went on to marry Eugene Manet, Edouard’s younger brother.

Berthe Morisot in 1873, was invited by Degas to join the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors and Printmakers (‘Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs’)- a cooperative that was dedicated to hold exhibitions freely outside the clutches of the jury from the official Salon. Although both Manet and her friend Pierre advised her against it, Morisot agreed to become a founding member, the only female artist in a group of 11.

In the spring of 1847, the anonymous society staged their first impressionist exhibition, along with 9 canvases by Morisot included in the display. Her paintings were shown in all but one exhibition held over the course of the next 12 years, that too only because she was recovering from the birth of her one and only daughter Julie.

Morisot through all these exhibitions, established her position in the milieu of avant- garde artists. ‘Her style became synonymous with Impressionism in the public consciousness’, and in 1881 the art historian Gustave Geffroy proclaimed that ‘no one represents Impressionism with more refined talent or with more authority than Morisot’.

On Berthe Morisot’s death certificate, She was listed as someone “without profession”. Even the street that she lived on has been robbed of her legendary artistic identity. The street where Berthe lived and worked was renamed after Paul Valery, a French poet and philosopher who married Morisot’s niece and lived in the house that she built.

The Patriarchy’s deliberate attempts at the erasure of women and their legacy have often been an age-old tactic to remain in control. By remembering a legend like Berthe Morisot today, we take one step forward to believing in Art and its power in bringing worlds, communities and identities together beyond the limitations of space and time.

Pari tiwari is a third year english literature student at Delhi University. She is interested in art, Feminism, politics of representation, literature, philosophy, film, and photography.