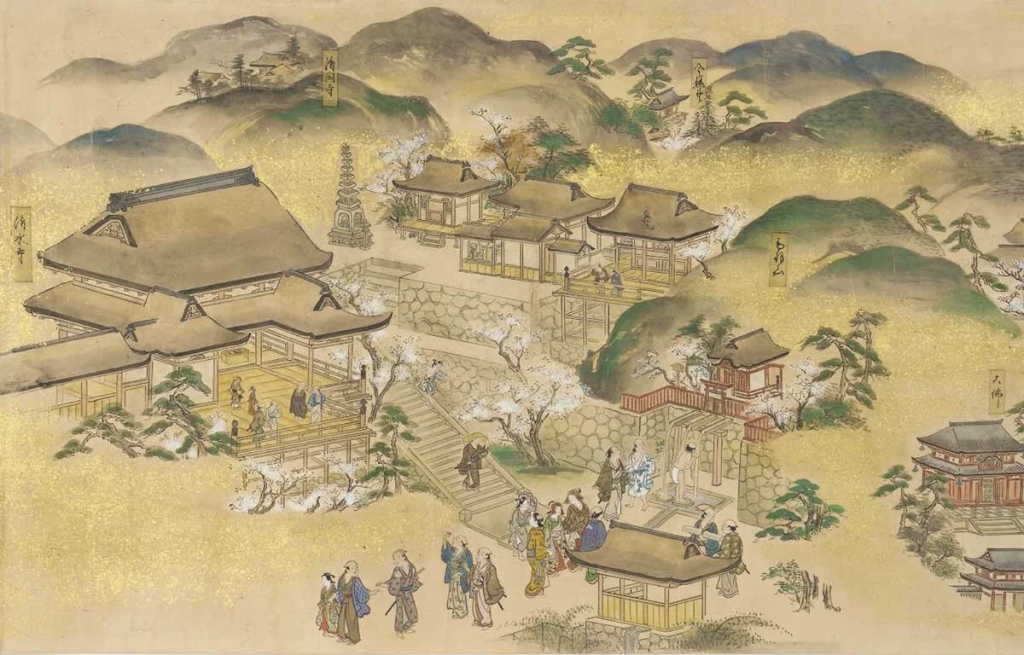

Traditional Japanese scroll paintings, also referred to as kakemono or kakejiku, represent an ancient tradition of Japanese visual culture that has been in practice for centuries. Painted works, usually on paper or silk, are mounted on scrolls intended for hanging on walls. For both their ornamental and practical functions, scrolls have been highly valued in Japan for centuries due to their capacity to combine visual beauty with deep cultural and religious significance.

Origins and Development of the Scroll

The emaki, or horizontal handscroll format, produces a complete, nearly cinematic experience of viewing. The story unfolds step by step from right to left as the viewer unrolls one side and re-rolls the other. With this format, rich storytelling from scene to scene can be expressed and was frequently shown in multi-scroll sets to tell more extended epics. Commissioned primarily by the elite imperial families, shoguns, and monks in wealthy Buddhist temples, emaki blended lovely calligraphy and complex paintings, generally done by official court artists. The written text normally came before the images, though it was sometimes inserted among the pictures.

The handscroll is thought to have had an Indian origin prior to the 4th century BCE, mostly utilized for religious texts. It was transferred to China by the 1st century CE and to Japan about the 6th century, accompanying the spread of Buddhism and other cultural developments, such as the Chinese writing system. Japan’s oldest dated illustrated handscroll, portraying scenes from the Buddha’s life, is dated to the 8th century.

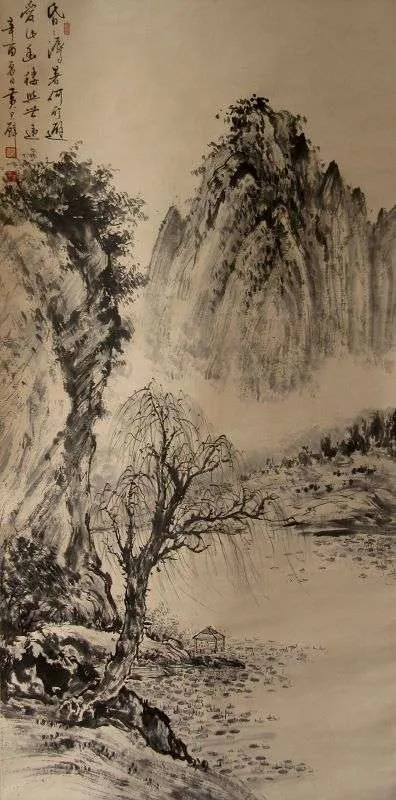

Early narrative scrolls in China developed during the 4th century CE, with an intention to impart Buddhist moral teachings. The genre evolved by the 7th century to become a core element of Chinese visual narrative. The landscape handscroll (makimono), which emphasized scenery over narrative, thrived in the 10th and 11th centuries in the hands of artists such as Xu Daoning and Fan Kuan. These paintings encouraged observers to embark on a ride through time and space, frequently leading the viewer’s eye along a twisting road or trail. No more than two feet (0.6 meters) of a scroll was intended to be seen at one time, preserving the closeness of the artwork. Artists addressed the problem of multiple vanishing points required to create the illusion of movement by ever so slightly changing viewpoints along the scroll.

From Handscroll to Hanging Scroll

Along with the resurgence of classical Chinese aesthetics, there came a vertical display alcove called the tokonoma within Japanese interiors. This architectural element created a vertical hanging scroll (kakemono), revolutionizing the scroll’s orientation from horizontal to vertical. These works were more stationary and reflective, coming closer to Western painting conventions.

Motifs and Influence

Generalized motifs in Japanese scrolls consist of ethereal landscapes, calligraphy flowing freely, and serene views of nature or everyday life. Japan has an art tradition dating back more than 12,000 years, and it is one of the world’s oldest. Some early art forms consisted of heavy clay pots with simple decoration shapes that remain with Japanese tableware even today. Scroll painting belongs to a wider tradition in Central and East Asia. Vertical scrolls thangka, used in Buddhist ritual, can be found in the Himalayas. East Asian horizontal scrolls, particularly those from China, Korea, and Japan, are concentrated on narrative and landscape painting.

In conclusion, Japanese scroll paintings, whether the vertical kakemono or the narrative emaki embodies a rich convergence of artistic expression, spiritual tradition, and cultural exchange. Rooted in centuries of influence from India and China, these scrolls evolved into distinctly Japanese forms that not only adorned spaces but also engaged viewers in immersive, meditative experiences. With their delicate brushwork, calligraphy, and evocative storytelling, scrolls reflect Japan’s deep appreciation for nature, transience, and quiet contemplation. Even today, these timeless art forms continue to inspire artists globally, serving as a testament to Japan’s enduring artistic legacy.

Featuring Image Courtesy: Image Courtesy: Japan Objects

Minerva is a visual artist and currently serves as a sub editor at Abir Pothi.