Part Two

The passage of time is always marked by the disappearance of that which once was. Whether through neglect, disinterest, or systemic erasure, the stories we fail to remember can be lost forever. Yet, in the practice of memory work, there exists a counterforce: a quiet persistence. This persistence, embodied in the work of artists and archivists across Goa, takes many forms. It is the act of retrieving, of patiently listening, of coaxing out stories that were never intended for history books but exist nevertheless, in family albums, oral traditions, and cultural practices

that persist despite the overwhelming tide of modernisation.

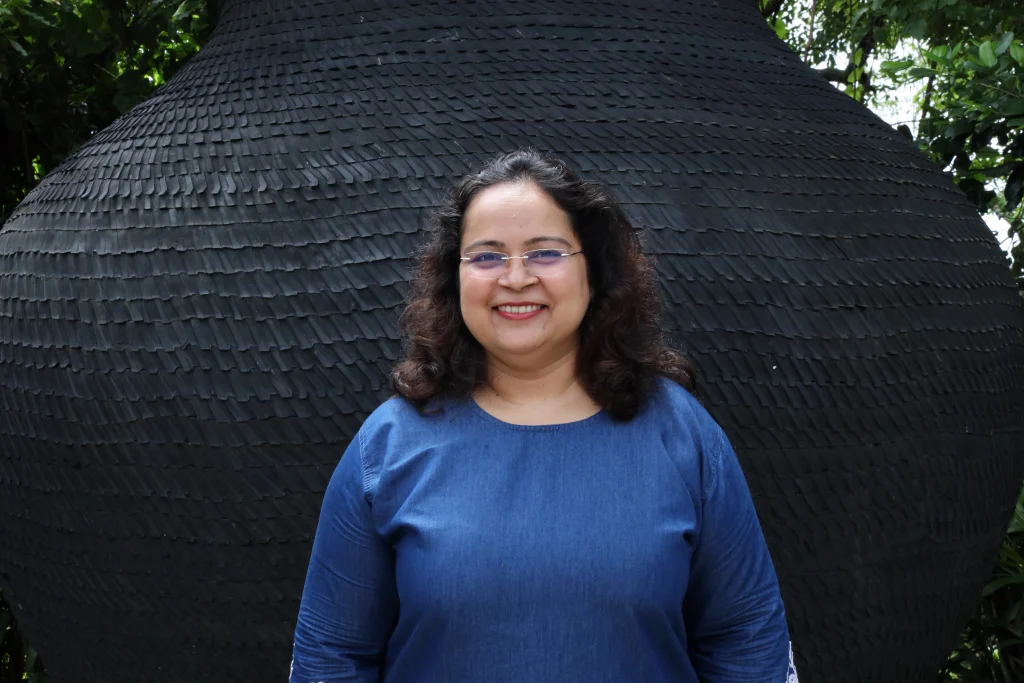

Lina Vincent, a seasoned art historian and curator, emphasized this ethic of persistence. “One size doesn’t fit all,” she remarked, acknowledging the immense complexity of working with personal and community archives. “With each person or each family, you really have to figure out the best way to do things.” Vincent’s approach is multifaceted, involving the use of audio and video recordings, digitisation of materials, and collaboration with various local institutions. Yet, despite the technical advancements, she recognises that every archive is inherently human, shaped by relationships and trust. The challenge, she noted, is “getting people to open their cupboards” and share their stories, particularly in a society steeped in suspicion and guarded

about its own history. This process of building trust is not immediate; it requires patience and a sensitivity to boundaries. “We have heard sacred stories,” Vincent revealed, “but we have not put them online because they cross certain boundaries.”

The stories that emerge from these archives are often rich with complexity, challenging mainstream narratives and sometimes contradicting the very history that has been passed down through official channels. This tension between personal history and public record was echoed by Hansel Vaz, founder of Cazulo Feni. Vaz’s work, centered on Feni, the traditional Goan spirit made from cashew or coconut—reveals the intersection of class, caste, and cultural identity in Goan society. “Feni is not just a drink,” he argued, “it’s a caste issue.” The historical neglect of coconut Feni, in particular, he noted, stems from the fact that it was produced by lower-caste distillers, whereas cashew Feni was more aligned with the upper echelons of Goan society. Thissocietal division, Vaz explained, has resulted in a profound invisibility for the workers and the craft, with no photographic records or formal acknowledgment of the process. His efforts to capture images of Feni production, through collaborations with photographers like David

D’Souza, aim to correct this absence in history, ensuring that the cultural and labor-intensive practices that go into making Feni are documented for future generations.

For Vaz, the work of archiving is as much about social justice as it is about cultural preservation. “The schism goes so deep,” he lamented, referring to the dissonance between how different classes perceive and value Feni. The absence of documentation, he continued, has prevented Feni from receiving the recognition it deserves. “There’s not a single book on Feni,” he remarked, noting the absence of visual and written records that could help bring attention to the craft. Yet, despite these challenges, there is hope – hope that the work being done today will eventually serve as a repository for future generations to understand and appreciate the complexity of their cultural heritage.

Sonia Shirsat, a prominent Fadista, also reflected on the challenges of preserving an art form that has deeply embedded itself within the cultural fabric of Goa. Fado, a Portuguese genre that has found a home in Goan society, is increasingly at risk of being lost to future generations. “The families that spoke Portuguese had pianos in their houses, could afford Portuguese guitars,” she explained. However, with time, the instruments have fallen into neglect, and the art form has begun to fade from public consciousness. Shirsat’s efforts to revitalise Fado through teaching and performance are a direct response to this cultural erasure. “There are Portuguese guitars in the possession of families in Goa,” she lamented, “but nobody plays them.” Despite the technical challenges in sourcing and maintaining these guitars – an instrument essential to Fado – Shirsat remains committed to ensuring that the art form does not disappear.

Her work extends beyond performance. In her efforts to teach Fado, she aims to reconnect a new generation with this art form, teaching them the songs and the cultural context that made them meaningful in the past. Yet, Shirsat also recognises the broader implications of archiving,

which is about more than just preserving music. “If you have anything written, I urge you, share it,” she implored. The lack of access to historical music collections and songbooks, often locked away in private homes, is a barrier to a deeper understanding of Goan music’s history. “That’s

how you create parallel histories,” she said, urging families to digitise and share their treasures so that future generations might benefit from the same cultural wealth.

In both Feni and Fado, as well as in other forms of cultural memory, the narrative is shaped by the invisible labor of those who keep these traditions alive. For Shirsat, as with Vincent and Vaz, archiving is not merely about preserving what is already known, but about creating spaces for dialogue, collaboration, and community ownership of history. The act of remembering, as Vincent suggests, is inherently a collective one. “People are starting to look at their own families and build up these stories,” she noted. “I think there is hope.”

The future of cultural preservation, however, is not solely the responsibility of artists and archivists. It is a shared task that involves communities, individuals, and institutions working together to ensure that the memories of the past are not lost. The platform Absent Archives represents this collective effort, offering a space where stories can be told, shared, and archived for posterity. As each generation passes, the urgency grows. “We are losing language, we are losing recipes,” Shirsat observed. “Everything is interconnected, music, dance, food, drink, living – it’s all together.”

In this complex landscape of memory, the work of Absent Archives and its collaborators is an act of preservation, also it is a form of resistance. It resists the forces of erasure, of cultural homogenisation, and of forgetting. It invites all those who engage with it to reflect on their own roles in this collective effort, to consider what they are leaving behind, and to ask what might still be saved if we act now. For, as the panelists demonstrated, even the most intangible of memories, when preserved, can become the bedrock of cultural survival.

Nilankur believes in the magic of critical thinking, intelligent dialogue and creativity. He stays in Goa, programs for the Museum of Goa and is a columnist.