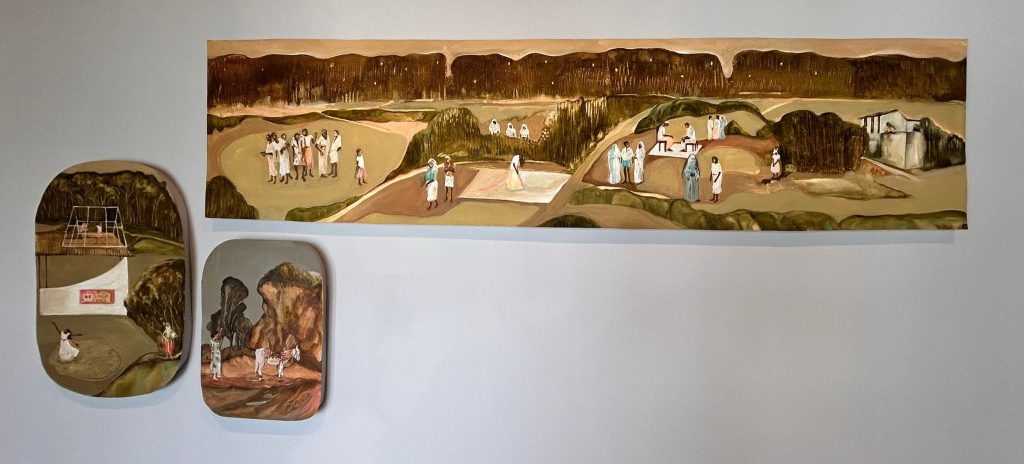

The paintings from Smita M. Babu’s series ‘Pakalam’, exhibited at the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, traverse the geographical peculiarities of the Ashtamudi Lake shore in Kollam, a region with numerous unique characteristics. Smita’s works, which hint at various aspects related to the coir industry, including occupations, history, and traditions, stand as a testament to how an artist embodies a place within her and transcends it. Works such as coir spinning and cashew processing have fostered a distinct work culture, and Kollam has a long-standing history of theatre and communism. There are two aspects of coir that immediately stand out as distinctive features of Smita M. Babu, setting her apart from other artists: one is the coir work culture, and the other is her connection to theatre. These two features come together in a way that becomes evident when observing Smita’s artistic creations.

The artist has over two decades of experience with theatre. What is here reflects the places seen through plays, and the perspectives developed through the places where they mature—the Pakkalam, a place where coir is made. It can be seen that the theatre world liberates Smita M. Babu. But beyond that, the Pakkalam actually liberate the region itself. The word ‘pakalam’ refers to a location where coir production occurs. While ‘pakalam’ can mean a workplace, beyond that, this place carries multiple meanings. For example, behind the word ‘pakalam,’ one should also see its meaning as a place that shapes and liberates. That is, a pakalam is not just a location, but also a place that liberates people, mainly women. The artist reflects on their own life through these artworks, located on the shores of Ashtamudi Lake in Kollam. When we say that these paintings reflect the coir manufacturing sector, the artist is attempting to present the worlds that emerge from it as reflections of her own world.

Coir production is an entirely women-centred workplace because women are often seen as more involved in this field. In that sense, these paintings serve as a visual testament to how Pakkalam is also becoming a place that liberates women. The paintings in the exhibition are entwined with personal memories and recollections of that place. In art, a place is both a person, a personal memory and a thing. In that sense, art is both a historical record of a place and a collection of visual memories. There is a wondrous world created by the life on the backwaters and its experiences. The intertwining of ripples and reflections of light on the water is magical, and through it, an enchanting inner world is constructed, which the painter conveys here without explicitly stating.

Smita’s artistic world is multifaceted. However, within the beauty of watercolour, those layers intertwine and become a genealogical, introspective essence of the place. The world created by combining layers of colours is entirely meaningful, yet abstract. That world belongs to individuals. Beyond that, it is liberated and, like a stage, becomes the focus of everyone’s attention. It is a place that glows in the light. Even if a leaf falls, the place remains transparent, known in essence to the land and its people. Smita designs canvas like an island. Each painting is imagined as an island, or as something yet to be discovered beyond predetermined structures, a space with its meanings, and the canvas itself is not a perfect circle or square; instead, it is in a form that does not conform to a specific shape. Within that shape, and parallel to it outside of it, the construction of the painting takes place. Therefore, beyond it, there are worlds created through images that evoke formlessness.

The poses of the women in the painting resemble those of a dance. The women in the painting are making movements that could become a dance if properly arranged with music. On that canvas, the Communist Party’s symbol (sickle and hammer) is painted on the wall. Nearby, a speaker in a coconut tree and garlands are also visible, along with a group of people walking through the area. In the painting, a theatre stage is being set up, or a play is being rehearsed. On the step leading into its light, a young woman is performing her role, practising it in a motion. What happens when we turn life experiences and their various undercurrents into images? How can we view another person’s experiences? Following these questions comes the realisation that what lies behind works of art is not just memory; moreover, art can shape the space itself and can be its very visual essence.

The aforementioned painting represents a unique blend of events that occurred in a region over various periods. One layer depicts the theatre that is part of the painter’s own life, while another portrays rural life associated with the stairs. The decades of theatrical life have provided the painter with a sense of dimension. On the canvas, the concept of theatre, as part of the composition, is transforming. The drama does not occur here, or rather, everything happens in the realm of drama. Drama influences the composition of these paintings and crosses their boundaries. In another painting, women can be seen holding their hands together. While there may be doubt whether they are dancing or practising dance, women nearby are seen busy with their work, coir making. In a circle, one can also see a red flag and someone cleaning the wall.

Along with the fact that the strokes of time cannot be erased, it can be seen that the strokes are being transferred into time, visually. One can see women taking coir from a coil and then going to the boat. One can also see a house, its inside and the people within. It is a fact that, by observing a group of people engaged in various aspects of life, one can also gain insight into the skills they possess and, through them, understand many of the things they have accomplished.

Through the concept of ‘assemblage’, Deleuze discusses various types of multiplicities. The reasoning that many have become one guides it. What we see and hear is just one of the many options that a thing presents. That may be the option at that particular time. At another time, a person may encounter or appropriate another version. This is where the relevance of Deleuze’s argument that ‘An assemblage in its multiplicity necessarily acts on semiotic flows, material flows, and social flows’ comes in. The creation and invention of various kinds of flows are taking place as the singularity of multiplicities. Multiplicities create the singularity of multiplicities. For decades, a painter in the theatre scene has transformed her own life into her paintings here. Moreover, as Deleuze himself states, through movements that can be described as an ‘assemblage of thought through visual,’ we can see her recording periods of time, indicating her position within them and conveying what the real world was like in the worlds she has observed and lived in.

If we borrow Deleuze’s own words, we can see that these paintings are a ‘Rhizome.’ It can be observed that the birth of these paintings lies in shapes that are shapeless/formless, beyond a fixed structural pattern. The energy of this reading stems from Deleuze’s view of the Bodhi tree itself as a rhizome. Beyond a fixed structure, the rhizome is a potentiality. While it indicates that anything can happen, there are perspectives and sounds beyond that. Everything that is said without being said contains a hidden meaning, a rhizome. Moreover, the way these aspects are filled, even in the shapes and sizes of Smita’s canvas, can be described as a kind of thin structure called rhizomatic. Deleuze states that there are no points or positions in a rhizome, unlike those found in a structure, tree, or root. That is, instead of a definite state, there is a motionless state; instead of rigidity, there is flexibility; and instead of delicacy, there is something else: a layerless state within many layers. The rhizome in the paintings can be seen as a perspective that blurs the distinction between inside and outside. Here, the real rhizome exists at heights or distances beyond the reach of an artist or the expressions put forward by an artist. When it is said to be determined, it is interpreted as something that can also be found behind the composition and formation of the paintings.

When we view Smitha’s artworks as a rhizome, we can understand the continuous journeys of paintings for existence and identity, especially in Smitha’s worlds, where there are multiple layers, including the land, its people, folktales, and theatre. The presence of the Communist Party is an integral part of Kollam’s geography, encompassing sectors such as coir- cashew work, trade union activities, and drama. When we also consider the party’s strength in Kollam, the region’s particularity becomes evident. Here, the serious intrusion of an artist’s pakkalam (film or play series) occurs. In it, the artists themselves transform into a rhizome, shaped along the Ashtamudi Lake and its surrounding areas, as a notion of region. Even though it has a definite form, conceptually, one can become a rhizome, a shapeless one. How would reflections occur for a rhizome that has transformed in this way? That’s what is happening here.

Deleuze’s answer to the question of how a tree firmly rooted in the ground transforms into a rhizome concerns the collective external intrusions of wind, birds, animals, and humans. The same applies to works of art. If a complete work can be seen as trees standing firmly rooted, a kind of life-wisdom emerges from its interaction with the humans who engage with it. This is where the thrill of Smita’s creations lies.

Krispin Joseph PX, a poet and journalist, completed an MFA in art history and visual studies at the University of Hyderabad and an MA in sociology and cultural anthropology from the Central European University, Vienna.