Artist Ali Akbar’s works, exhibited as part of the curated show at the ongoing 6th edition of Kochi Muziris Biennale, are entirely contemporary in nature, posing questions while also advancing the Biennale’s mission and challenging the legacy of colonialism through a visual dialogue.

These works directly and indirectly pose a multitude of questions to the spectator. In contemporary India, does it seem that a Muslim artist has some responsibility that a non-Muslim artist does not? Leaving the matter of the artist aside, what privilege does contemporary India give to a Muslim—is it the privilege of having no privilege, or the responsibility to become more patriotic, or else the mission of transforming into a more

exemplary Indian? What has contemporary India accorded to a Muslim? Here, the intention is to undertake the task of reading the works of the artist Ali Akbar. It is not the aim of this article to argue that all the problems faced by Indian Muslims are reflected in these paintings, nor is that the scope of this reading. However, the goal is to look at the paintings, read them, and explore their various possibilities.

Perhaps the most significant challenge a Muslim artist faces in contemporary India is the possibility that his artworks may be misinterpreted—or even misread—in specific ways. Since artwork is a world of images, colours, compositions and meanings, one could even say that this makes art possible; however, it also carries its own dangers. The fact that interpretation (or viewing) can simultaneously turn into misreading is also a problem. Such an additional burden is not imposed on the artist in this case.

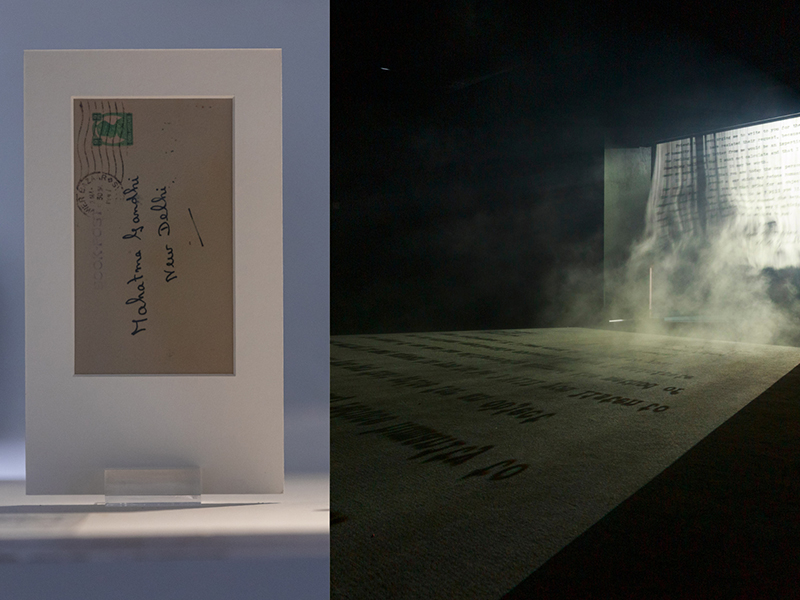

The dictionary meaning of the word ‘reliquary’ is ‘a container for holy relics.’ However, by making it the title of his exhibition, artist Ali Akbar frees the word from its dictionary meaning and expands it into worlds of broader significance. The collection titled ‘Reliquary,’ marked as an ongoing series, raises the question of whether it merely liberates the word from its meaning or creates an atmosphere that reads both the word’s meaning and the ‘spiritual’ environment it generates in connection with a political body, which is the artist’s habitat. Here, we can see that the artist is the greatest creator of meaning. The images he produces and creates, and the colours he applies to them – if they are colourless, it becomes a bit more complicated, and one has to recognise that there is a deeper meaning as well.

Derrida’s question, ‘Is an architecture of the event possible?’ is relevant here. That question is not about the architecture, but rather about the event that it creates, which in turn influences the architecture of paintings. If we consider Ali Akbar’s artworks as revealing space and time from history—the spaces of both the artist and the time he lives in—as events, then what would be the architecture of that event or those events? That is the question being posed. If we can view history as a flow and the occurrences within it as events, we can say that there is an answer to Derrida’s question in art; art

always displays everything, including the events as spectacle, displayed and thus readable.

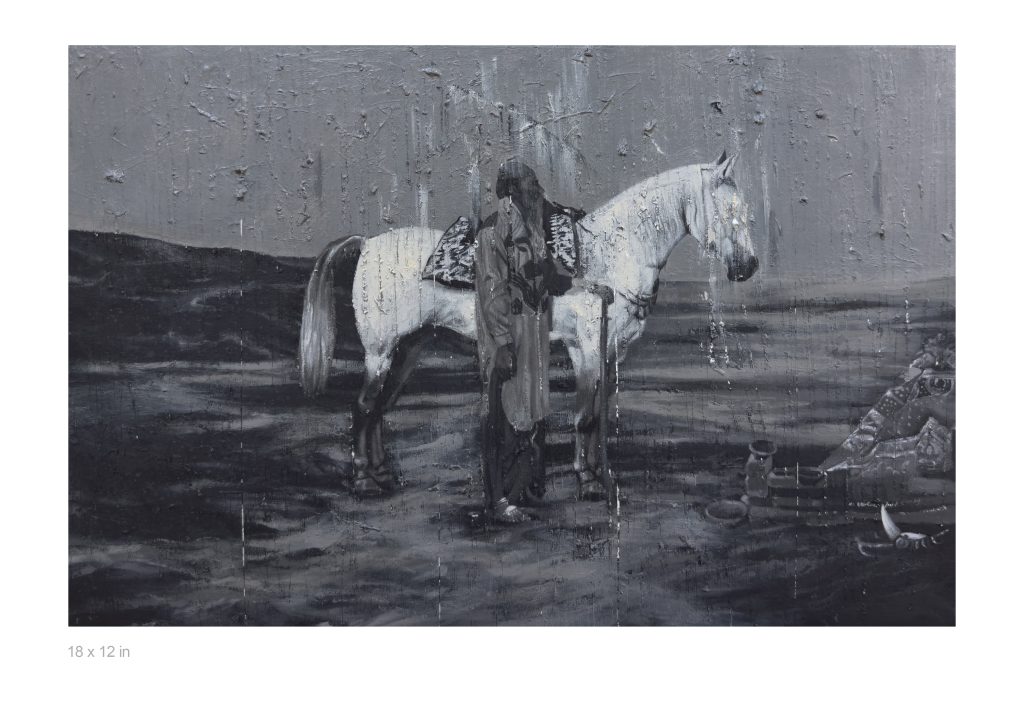

When Derrida says ‘everything marks an era,’ he is referring not only to the period of each thing but also to the misreading of time. Just as one can set a specific time for any ‘creation’, it is also possible to misplace time within that—the unique nature and potential of art lie in its ability to reposition time. The contemporaneity we see in art, in that sense, is maybe an interpretation of antiquity. Art is essentially an interpretation of a concept, and visually narrates ‘what is there’, a composition, while precisely distorting what is intended to be read, for example, the efforts to tame a horse and establish

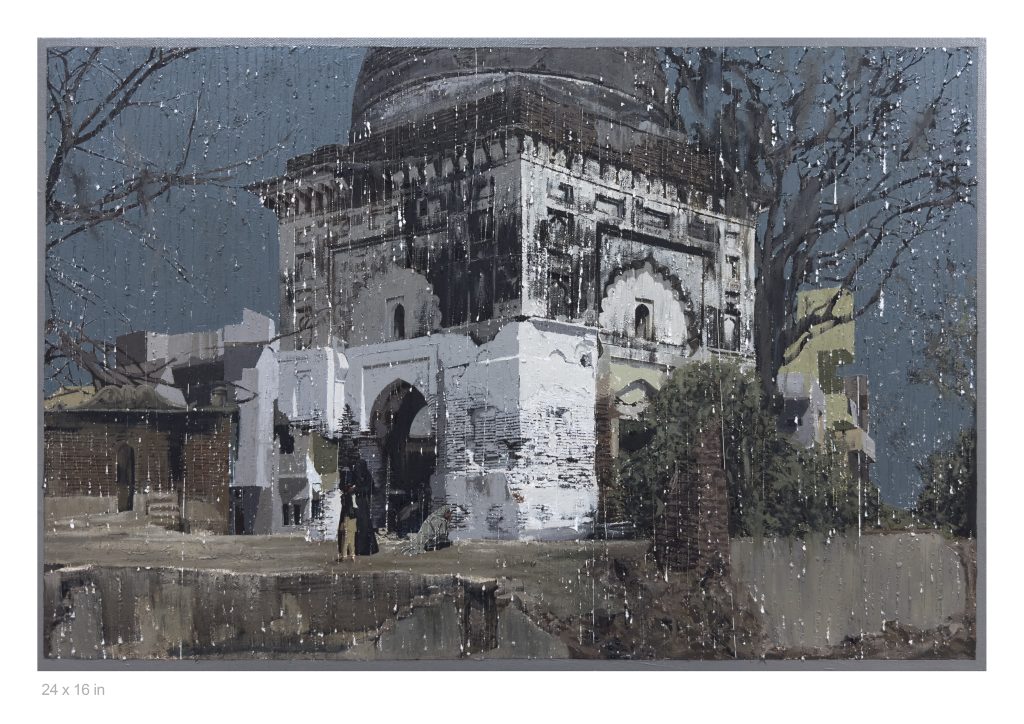

dominance over it are what, on the surface, the work ‘Anatomy of the Surge’ depicts. Still, in the context of a mosque, the events in the work take on a different meaning, especially since Arabian horses appear as a legacy of the Sultanate-Mughal-colonial period. The scene of people playing near a mosque is transformed here into the act of taming a horse. Through this transformation, a reinterpretation of history and an artistic creation are created.

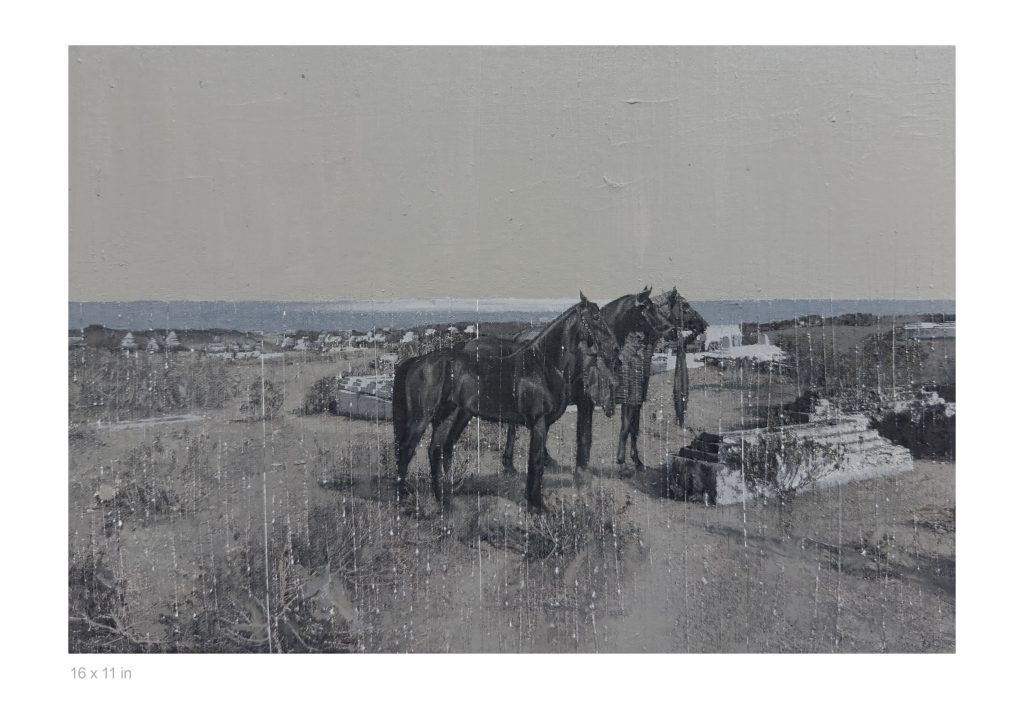

While the mosque and the game happening nearby are realities, the idea of taming a horse, as applied by the artist, is introduced in this context. What was once merely a game near a mosque is now transformed into an image where the concept of taming an Arabian horse, along with its Sultanate, Maratha, Mughal, and colonial backdrop, is layered one upon the other to form a visually coherent work. Even today, the horse remains a cultural and symbolic visual image, playing a prominent role as the primary guest in many essential ceremonies, from weddings to Mukharaam processions. This distinguished guest finds its way into Ali Abkar’s artistic creations in various forms, and it can be interpreted in multiple ways: as a reflection of colonialism, the embellishments it underwent, Arabian traditions, and its various manifestations.

Just as the horse tamed against the backdrop of the shrine becomes both a symbol and a metaphor, horses pass through in many ways. That horse carries a history. That history is a narrative with multiple layers. It is one of the many connections that weave that narrative together, like an architecture, so is the horse. Grooming that horse involves grooming the place, the language, and the people. Here, we can observe various combinations of events that occurred during the colonial period. While the presence and background of the horse aid in intertextual readings, the architectural background can be seen as reinforcing its meta-narrative. For example, in the painting “A Breath Against the Skin of Night,” the visually recreated subject is a tomb of an Arab Jamadar, which the Maratha king had invited and which had been demolished a few months ago. Since it wasn’t photographed before its demolition, the ‘tomb’ has been recreated based on models of the remaining tombs in the area. Near this tomb, the first

Eidgah in Baroda was held. Through the spaces that disappear, the various undercurrents that shaped, created, and formed both the history and the space are also lost.

The influence from various sources, including portraits of people from the Mughal period, is evident in these paintings. Images documented and seen at multiple sites are incorporated into this work. Whenever the archival process is apparent in the work, it is presented in a distorted manner. In it, a layer from the Sultanate, Maratha, and Mughal periods appears, followed by a layer of an object or structure from the colonial period. When thirty to forty layers appear in a collage, it is impossible to say which layer the viewer is stuck in. Since one can get caught in a different layer at any moment, it also becomes a fact that it turns into an unlimited visual experience. Many cultures have a history that predates the advent of trade and commerce. The voyages between the coasts of Kerala and Gujarat and the exchanges that took place through them are noteworthy. The artist mentions that while there is a story to tell about his homeland and its coastal heritage, as well as about the seaside life and heritage of Gujarat, where he currently lives, along with centuries of cultural and social history, he attempted to create a parallel ‘coast’ in between them.

The underlying current of these themes is the poetic history of Gujarat’s coastal regions, explored through its rich cultural heritage, including its Sufi shrines. In the meantime, many places, including numerous dargahs, are being demolished. What is happening now is a history being constructed through demolition. Here, efforts are being made to observe the absurdities of that historical (re)construction of demolition. Bahri and Qutb

are images associated with two locations that have a background of horse trading and taming. The word ‘Bahri’ is used in two senses: being in the sea and being from outside. The world of meanings created by this usage somewhat broadens the worlds that the artist presents.

The artwork ‘Anatomy of the surge’ is created from the remnants of the pillars of a Juma Masjid. In situations where many of them are destroyed, and claims are raised, questions about how an architectural form endures and what constitutes an architectural form are also raised. We can see through these images the possibilities of resisting the meta-narrative that everything was originally a temple and only later became a mosque. It is also evident that behind these creations is the question of how meta-narratives opposing the tendencies to divide society and turn people into impostors are generated. In Derrida’s argument that ‘We appear to ourselves only through an experience of spacing that is already marked by architecture,’ space is considered a component that reconstructs our very experience, in the sense that architecture serves as the ‘Mirror’ of the self. Just as you need a mirror to see your physical face, you need architecture (built space) to see your social and psychological existence. In this way, space determines and advances our lives. Through Derrida’s argument, Ali Akbar’s paintings can be seen as presenting an architectural composition in a similar and distorted manner.

Why does Derrida answer the question of ‘architectural’ with ‘it penetrates us’? It influences us so profoundly and unsettles us, yet at the same time, the argument that the architecture is a hierarchical nostalgia is also put forward. That is, the idea is that the architect is materialising a hierarchy. Therefore, the ‘architectural nostalgia’ shaped through Ali Akbar’s images can be said to represent a kind of hierarchy. However, the architects depicted are either erased, on the verge of destruction, or caught in conflict. Hence, although they evoke the hierarchy of a certain era, it is ‘non-hierarchical’ now. If hierarchy is a claim, those liberated from it should be considered free from hierarchy. However, what becomes evident through Ali Akbar’s paintings is their terrifying depiction. Ali Akbar is a multimedia artist. Through these artworks, the mental state of someone who delves into the essence of chronicles spanning across realities, myths, history, fiction, and folklore becomes evident. Here, a new history is being created through the meticulous interweaving of oral histories and museum-archive records within historical constructions.

It examines the continuous harmony in the celebrated past constructions of India, including those crafted by Hindu and Muslim artisans, as well as the artistic endeavours stemming from Indo-Muslim-Buddhist thought behind them, and the chaotic atmosphere that has continually existed within these architectural traditions.

Cover image:A Breath Against the Skin of Night

Krispin Joseph PX, a poet and journalist, completed an MFA in art history and visual studies at the University of Hyderabad and an MA in sociology and cultural anthropology from the Central European University, Vienna.