In the revolutionary ferment of early 20th-century Russian art, few figures proved as transformative as Mikhail Fyodorovich Larionov. Born in Tiraspol, a city near Odessa, Russia (now Odesa, Ukraine), on June 3rd, 1881 on the periphery of the Russian Empire and dying in Parisian exile, Larionov’s artistic journey embodied the tumultuous cultural shifts of his era while establishing him as a pioneer of pure abstraction and a founding father of luchizm (variously translated in English as Rayonism or Rayism. With works encompassing folk art, icons, prints, modern science, and optics, Larionov, along with his partner, Natalia Goncharova, was responsible for introducing not only the first non-objective painting style in Russia, but also a new distinctly Russian style of painting that eschewed Western influence in favor of models based in Russian history and experience.

Who was Mikhail Larionov ?

Mikhail Larionov brought Russian art from its provincial backwardness into the vanguard of international modernism. As an exhibition organizer, theorist, and artistic innovator, Larionov possessed what one scholar termed “shrewd propagandist” instincts for promoting both his own legacy and the broader cause of Russian avant-garde art. His partnership with fellow artist Natalia Goncharova, whom he later married, became one of the most influential creative collaborations in modern art history.

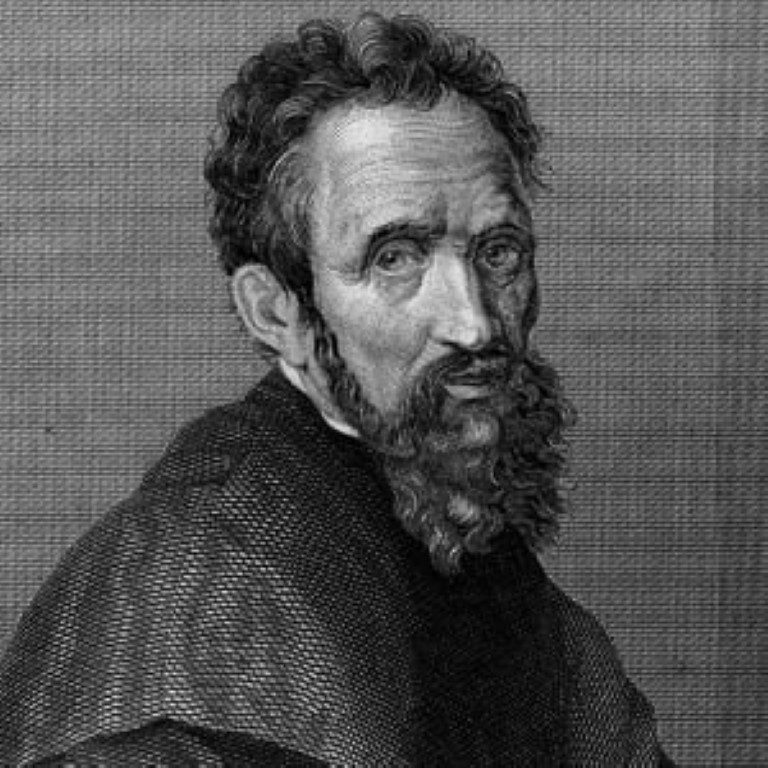

Mikhail Larionov. Image courtesy: Wikipedia

Early Life and Education

Born June 3, 1881, in Tiraspol, near Odessa (now in Ukraine), Larionov emerged from the culturally diverse borderlands of the Russian Empire. After completing secondary education at Moscow’s Voskresensky Technical High School, he enrolled at age 17 in the prestigious Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. It was there, in 1900, that he encountered Natalia Goncharova, beginning a partnership that would reshape Russian art.

Larionov’s early artistic development reflected the cosmopolitan influences available to ambitious young Russians of his generation. His initial works embraced Impressionist landscapes, several of which he exhibited at Paris’s Salon d’Automne in 1906. This early exposure to contemporary French painting proved formative, introducing him to Post-Impressionist and Fauvist innovations that he would later synthesize with distinctly Russian elements.

Artistic Development and Major Works

Larionov’s artistic evolution moved through several distinct phases, each marking significant developments in Russian modernism. His early Symbolist period, exemplified by works like “Evening after the Rain” (1909), employed the bright colors and coarse brushwork characteristic of Fauvism. However, it was his groundbreaking painting “Glass” (1909, though possibly backdated from 1912) that marked his transition to pure abstraction and the birth of Rayonism.

Rayonism, Larionov’s most significant theoretical contribution, emerged from his study of optics and theories of perception. As he wrote in his 1913 manifesto, Rayonist painting aimed to capture “the sum of rays reflected from the object,” translating light rays into echoing lines of color. This approach, he claimed, “erases the barriers that exist between the picture’s surface and nature.” Works like “Rayonist Composition: Domination of Red” (1912-13) demonstrated this revolutionary technique through masses of slanting lines representing painted rays of light.

Simultaneously, Larionov and Goncharova developed Neo-Primitivism, a movement that deliberately rejected Western influence in favor of Russian folk traditions. Drawing inspiration from Orthodox icons and colorful woodblock prints known as lubki, Neo-Primitivist works like “Boulevard Venus” (1913) combined Cubo-Futurist techniques with distinctly Russian cultural references. This fusion of radical formal innovation with national artistic traditions distinguished Russian Futurism from other avant-garde movements of the period.

Sea Beach and Woman. 1911. Oil on canvas – Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany. Image Courtesy: Wikipedia

Exhibitions Championing Russian Cultural Independence

Larionov’s organizational activities proved as influential as his painting. In 1908, he co-organized Moscow’s first significant exhibition of French Post-Impressionist and Fauvist painting with the arts journal Zolotoye runo (Golden Fleece). Two years later, he co-founded the Bubnovyi valet (Jack of Diamonds) group, composed of Russian artists interested in Primitivism and folk art appropriation.

Growing increasingly committed to Russian cultural independence, Larionov and Goncharova established the more radical Oslinyi Khvost (Donkey’s Tail) group in 1911. This collective focused exclusively on Russian primitivism, rejecting foreign influences entirely. The group’s 1912 exhibition at Moscow’s Stroganov Art Institute and its 1913 journal “Oslinyi khvost I mishen” (Donkey’s Tail and Target) became crucial platforms for promoting indigenous Russian modernism.

The year 1913 marked Larionov’s theoretical peak with the publication of three Rayonist manifestos outlining his revolutionary approach to non-objective painting. These writings fascinated the international avant-garde and established Rayonism as Russia’s first fully abstract art movement, predating even Kandinsky’s pure abstractions.

Peasant Women Bathing. 1909. Oil on canvas. 89 × 109 cm. Image courtesy: Kovalenko Regional Art Museum, Krasnodar

Contemporaries and Further Collaborations

Larionov’s career intersected with virtually every major figure in Russian modernism. His closest collaborator remained Natalia Goncharova, whose parallel artistic development complemented his own innovations. Together, they influenced younger artists like Kazimir Malevich, whose Suprematist movement built upon Rayonist foundations.

In 1914, Larionov and Goncharova joined Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, bringing avant-garde sensibilities to international theater. Larionov’s designs for ballets including “The Midnight Sun” (1915) and “Russian Tales” (1917) extended Russian Futurist influence beyond painting into performance art. His sumptuous designs for Russian Tales, based on Russian folktales, solidified his international reputation and demonstrated how traditional cultural elements could be transformed through modernist techniques.

After settling permanently in Paris in 1919, Larionov continued collaborating with Cubist and Dada artists while serving as cultural ambassador for Russian art. His organization of the first major modern French art exhibition for the Soviet Union in 1928 at Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery maintained crucial cultural bridges despite growing political tensions.

Legacy of Abstraction

Larionov’s influence on Russian art proved both immediate and enduring. Rayonism, despite attracting few direct followers, established crucial precedents for Russian abstraction. His focus on painting’s essential elements—color, shape, and texture—rather than subject matter or symbolism provided foundation stones for both Suprematism and Constructivism.

Beyond formal innovations, Larionov’s greatest legacy lay in demonstrating how national artistic traditions could be transformed rather than abandoned in the pursuit of modernist goals. His integration of Russian folk culture with international avant-garde techniques created a distinctly Russian modernism that avoided both provincial backwardness and slavish imitation of Western models.

Though Larionov spent his final decades in relative obscurity, dying in poverty at a Parisian rest home in 1964, recent decades have witnessed renewed appreciation for his contributions. Major retrospectives at institutions including the Centre Georges Pompidou and multiple international venues have restored his reputation as a pivotal figure in early 20th-century art.

Mikhail Larionov’s career embodied the contradictions and possibilities of his revolutionary era. Born on the margins of empire, he helped create an artistic movement that challenged the supremacy of Western modernism while remaining thoroughly international in scope. His synthesis of Russian folk traditions with radical formal innovation provided a template for cultural modernization that avoided both reactionary nationalism and cultural self-negation. In bridging the gap between Russia’s artistic past and its modernist future, Larionov established himself as an indispensable figure in the history of 20th-century art—a visionary whose influence extended far beyond the brief flowering of Russian Futurism to touch virtually every subsequent development in Russian visual culture.

Contributor