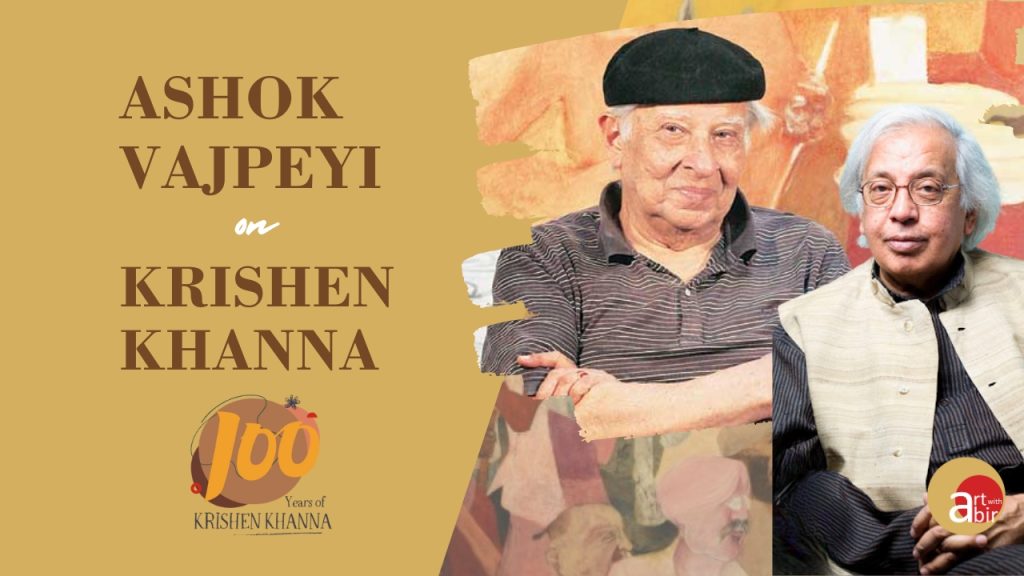

Excerpts from the conversation between Poet and eminent Cultural Critic Ashok Vajpeyi and Abir Pothi Founder Nidheesh Tyagi

Krishan Khanna: An Unusual Modern Master

Krishan Khanna is a very unusual modern artist. This modern master has attained the age of one hundred. The Progressive Artists Group, of which he was a member, had artists who lived long lives. Many of them – Hussein, Ram Kumar – went beyond 90. Hussein, I think, reached 96 and a half or 94 and a half. But Krishan is the last standing man at 100.

If you look at the entire history of modern Indian art, it’s about 120 years old, out of which Krishan Khanna has been painting and has been a presence for 80 years. He came to art from a rather elite background. His father was a university professor. He was schooled in Great Britain and had a job in Grindlay’s Bank, which he resigned to devote himself entirely to art. So here is a man who took to art by leaving everything else behind.

He was not only an artist in his own right – a major artist – but also an intervener in the art scene, in terms of his views, in terms of helping others, in terms of taking part in important institutional activities, like the Triennale and the Academy, or the Roopankar Museum.

He has been a great letter writer. We have published his correspondence with Raza in a substantial volume, and there are any number of other artists with whom he carried on correspondence.

Epic Imagination

His imagination, I believe, has been, in many ways, an epic imagination. In other words, it is an imagination which covers the classical and goes on to include the subaltern. So he has painted Bhishma Pitamah, he has painted Christ, he has painted Gandhi, he has painted the Last Supper – fairly classical themes. But he has also painted the banjaras and the truck drivers and such subjects.

His range extends from the narrative to the non-narrative to the abstract – large works, murals, 80-feet-long paintings. These are, even in terms of sheer craft, amazing attempts.

All in all, I would say that Krishan Khanna has been a kind of chronicler of human suffering, human dignity, human predicament, and human tragedy of his times. To chronicle all this, what you need is an epic imagination, because then alone you can include several aspects. So he stands very tall among the moderns.

The Progressive Artists Group

What is surprising about this Progressive Artists Group is that almost every member stood very tall. There is no group of artists in India, and I wonder if in the world as well, where a single group had such masters: Hussein, Raza, Souza, Ram Kumar, Gaitonde, Tyeb Mehta, Akbar Padamsee, and Krishan Khanna. It’s an amazing group.

In Krishan Khanna, there is also the organic link between the creative and the critical. If you read his correspondence or his writings, you’ll find that he is a fine critical mind. He is one artist who can recite by memory a poem by W.B. Yeats, for instance, “Sailing to Byzantium.” He remembers by heart parts of “Four Quartets” by T.S. Eliot. He can recite from a little-known American poet, Conrad Aiken. He was, of course, trained in England, but he also knows Urdu and Persian. Many important contemporary international artists were his personal friends. So he has had a very illustrious career.

Witness to Partition

He was also a witness to partition and saw the freedom movement. On one level, he’s very cosmopolitan, and on another, you’ll find lots of Punjabi influences coming into his work. He was one of those artists who had to leave erstwhile West Punjab to come to India, and some of his works relate to partition.

It’s interesting to note that the most significant works in North India on partition, whether in visual arts or in literature, have been done by those who were originally Punjabi, coming from present-day Pakistan. For instance, Krishan Chander, Krishna Sobti, and Bhisham Sahni – they all migrated from Pakistan to India and wrote some of the best literature on partition.

Krishan Khanna came to Delhi at a time when most of the cultural world of Lahore had shifted to Delhi after partition. It was both a question of rehabilitating themselves, and for a while, they were not exactly exiles, but refugees. These artists sought refuge in a country which had been partitioned, having to leave their homes, hearth, land, and memories behind. A lot of their art was to rehabilitate that, to recapture it in their art.

Artists like Satish Gujral, Harvesh Sanyal, Krishan Khanna, and sculptor Dhanraj Bhagat – they were not seeking refuge, but trying to retain what they had lost, both in memory and in creativity. It must have been very shocking at that point of time, but they were not going to another country – only to another part of the country. It was a breakaway of cultural continuity.

The Humorous Progressive

Among the Progressives, he was the funniest. He has a sense of humor and is a very articulate speaker – the most civilized speaker, with a lot of fun and humor, wit in it. Unlike some of the others – Hussein spoke very little, Souza spoke largely to shock and surprise, Raza spoke little, Gaitonde spoke nothing, Akbar spoke but was very contemplative, Tyeb Mehta was also a man of few words – among the friends, he was the most articulate.

He was also the peacemaker among them. He provoked them to remain in touch with each other, even when the group was formally dismantled, to write to each other and remain connected. When they had feuds, he was the peacemaker. So he was the link between these masters.

The Triennale Experience

I had the experience of working with him for a while during the Lalit Kala Academy Triennale – I think that was the best Triennale ever held, when Krishan Khanna and J. Swaminathan were handling it as the main curators. They asked me to take care of the International Seminar. This was in 1978-79.

I was quite amazed by his personal contacts with figures like Morris Graves, Harold Rosenberg, and Robert Motherwell – all these people came to the Triennale seminar. Among the Progressives, most of them were vulnerable and open to other arts. I proposed that the international seminar should not be confined to visual arts – we should have dancers, musicians, and theater persons. They very readily agreed, and we had Kelucharan Mohapatra and others participating. This had never happened before and never happened thereafter.

The Bharat Bhavan Connection

When we were putting together the State Gallery of Modern Art in Bhopal, I was trying to persuade Swaminathan to come and take over. Swaminathan and Krishan Khanna were in Garhi Studios in Delhi, and it was difficult for Swami to shift from Delhi to Bhopal. But Krishan Khanna was very supportive.

Krishan became one of the main supporters in acquiring works. Bharat Bhavan, at very modest prices, acquired the most representative works of modern Indian art in the late ’70s and early ’80s. The best public collection is with Bharat Bhavan – not with the National Gallery of Modern Art or with Lalit Kala Academy, which ought to have it.

When the BJP intervened and we were all thrown out, and Swami resigned, there was a protest demonstration in many cities, but more importantly in Bhopal. Krishan Khanna, Ram Kumar, Nirmal Verma, Manjit Bawa, and others all went to Bhopal to take part in that demonstration.

Major Art Requires Bold Imagination and Great Skill

Major art is possible only when there is bold imagination met with great skill, and Krishan Khanna has that great skill. His range, his lines, his drawings – I met him only yesterday to invite him formally to our celebration of his centenary, and he’s still painting. These days, he’s doing black and white drawings. He has done huge 80-feet-wide black and white drawings.

He wrote a letter to Raza saying that he thinks now he’s not interested in image – he’s interested in color. Reading that, I was surprised that here is a man who has handled so much color and has used color so beautifully, so evocatively, so intensely, so passionately, so inventively. Yet normally when we talk of color, it is Raza who is mentioned. Krishan Khanna is not mentioned, which is very unfair.

If you look at the range of colors that he handles – the banjaras and the various colors, the reds and deep magentas and all kinds of colors that the banjaras put on, or the truck drivers with their very multicolored vehicles painted all over – there’s a range of colors which he uses.

The skill is not limited to smaller works or large works, or to drawing or to painting. He has done some sculpture also. In whatever he has done, there is a distinctive mark of his skill. You can’t find fault. The picture, as he keeps saying himself, “must hold as a picture.” The theme is incidental. What is important is how you put the various elements together so that they hold together – that’s the main thing, the integrity of it.

Generous Artistic Vision

He has what you would call a generous taste. For instance, he goes to Indonesia to see Borobudur and writes to Raza that we moderns have been insisting on individual vision and individual effort, and we should not make this universal because it does not apply to many things. These monuments were done by a community of artists, and there is no individual’s name even available. This is true of our own Indian temples – you don’t know who built Khajuraho and such.

So there could be great art born out of community artistic effort, larger collective effort, with no insistence on individual stamp. In his own case, he has been largely a narrative artist, but he has been very appreciative of those who do non-narrative work, like Raza, Akbar Padamsee, or Ram Kumar with their various forms of abstraction.

He has an accommodative artistic vision which allows for other kinds. A great artist is one who looks uniquely at the world, but by the same token, acknowledges when faced with other kinds that there are other similar unique ways of looking at the world – that his way is not the only one. He had this generosity and receptivity in large measure.

Monumental Scale

Look at what he did in the dome at a venue, or the mural work – it’s amazing. And look at the color – it’s a kind of mela of colors, various and vibrant. He did something before this that was 80 feet wide in a hotel in Chennai. Later, when the hotel was renovated, they didn’t have space, so they cut it into pieces. Now they have brought it back, but they don’t have space where that 80-feet-long work can be displayed.

There’s something classical or monumental about his work, both in physical range and the range of space. Art, like music and literature, has two problems to grapple with: the problem of time and the problem of space. What do you do with time, which is so troubled, full of riddles and enigmas and mysteries and shocks and turbulence and tensions, joys and anxieties? And there is space – how do you people it, how do you fill it up, how do you create space and handle the physical space of canvas or wall?

To handle them both with imagination, with inventiveness, with a degree of allowing the material also to guide you – Krishan Khanna has been one of those who allow the materiality of objects, of color, etc., to lead to some meaning rather than imposing meaning all the time on the material.

Humanizing the Heroic, Elevating the Human

His ability to humanize all characters is remarkable. For instance, his “Last Supper” – The Last Supper is a great theme in Western art. The way he places them and the way they look, it doesn’t look like a Christian theme. It looks like a human theme, like people making bread together, people who are going to part the next day but sharing great bonhomie.

This is making the utterly heroic very human. On the other hand, he takes the very human – the banjaras, truck drivers – nothing heroic about them, almost subjected to inhuman levels, and makes them heroic. So you have this – this is what major art does. It pulls the heroic down to reveal the human in it, and it elevates the utterly human to heights where it appears grand and glorious and heroic.

Letters and Artistic Philosophy

From his correspondence with Raza, he writes: “I would extend your definition to say that every painting has a base in experience, which lies in itself and in reality.” There is a distinction he’s making between experience, which has to be personal, and reality, which has to be much larger. But for the painting to have meaning, it would require both – a personal experience and the larger reality. It’s only when the personal and the impersonal somehow meet or resonate with each other that a painting would hold itself.

He writes about his experience in Borobudur, Java: “I had heard that it was an impressive monument. But when I saw it, I was quite amazed. Its enormity and consistency quite overpowered me. The edifice was sculpted over a period of 180 years, which means that many generations of architects and sculptors kept up the work. The question arises as to how they maintained such consistency of style and quality.

“The answer that comes to my mind is that within the community there was never any question of another style, and sculptors were quite content to work within the given language of a particular style. Hence such a colossal achievement. By the very nature of our times and our emphasis on individual values, it is not possible for us to create such monuments. I am not bemoaning the fact, simply recognizing it, and it is this recognition which makes me realize that the accent on personal style must in fact lead to many kinds of art, not just one. It is therefore not rational to try and equate everything that is being done to a single norm.”

Lifetime Commitment to Art

The 80 years of artistic effort could not have been possible except through stubborn and uncompromising commitment to art. It requires a whole life commitment to art. He wrote: “I am desperately interested in my own work, and it takes up all my energy.”

Ultimately, what one can learn from Krishan Khanna is that art does not necessarily achieve something outside itself – art is achievement itself. Art is a human attainment which is not validated or expected by something beyond itself. Art is salvation in itself. Art is liberation. Art is the final human attainment.

He cannot be copied. The kind of uniqueness he has – most people have tried, other artists have tried, but you will always fail because colors are not just colors, lines are not just lines, shapes are not just shapes, figures are not just figures. They are deeply imbued with a personal touch, and that personal touch is unique. You cannot imitate it.

Subtlety cannot be copied. Hussein has different objectives – he was a figurative painter, and in Hussein’s case, there is a sense of play. Krishan Khanna has that sense of play too, but playfulness is not central to his work in the same way as with Hussein.

He has been perhaps the most politically aware of his group. He has always stood up vocally and firmly and strongly against communalism and against all these tendencies, and he has always joined protest demonstrations and movements.

Contributor