3D Technology Unlocks Ritualistic Ancient Greek Figurines

A groundbreaking collaboration between archaeologists and engineers reveals how ancient Greeks mass-produced votive figurines, and what these modest offerings reveal about daily life, belief systems, and craftsmanship in the early first millennium B.C.

On a Windswept Ridge in Crete, Ancient Secrets Lie Hidden in the Rocks

High above the Cretan landscape, atop the rugged ridges of Anavlochos, archaeologists are uncovering a mystery that has endured for over 2,500 years. Carefully nestled into the crevices of bedrock are hundreds of terracotta figurines, deliberately placed, many broken, all female.

These votive offerings, referred to affectionately by researchers as “The Ladies of Anavlochos,” are remnants of ancient spiritual practice. Now, through a combination of experimental archaeology and modern prototyping technology, researchers are breathing new life into these figurines, and the stories they were meant to tell.

Courtesy – Florence Gaignerot-Driessen

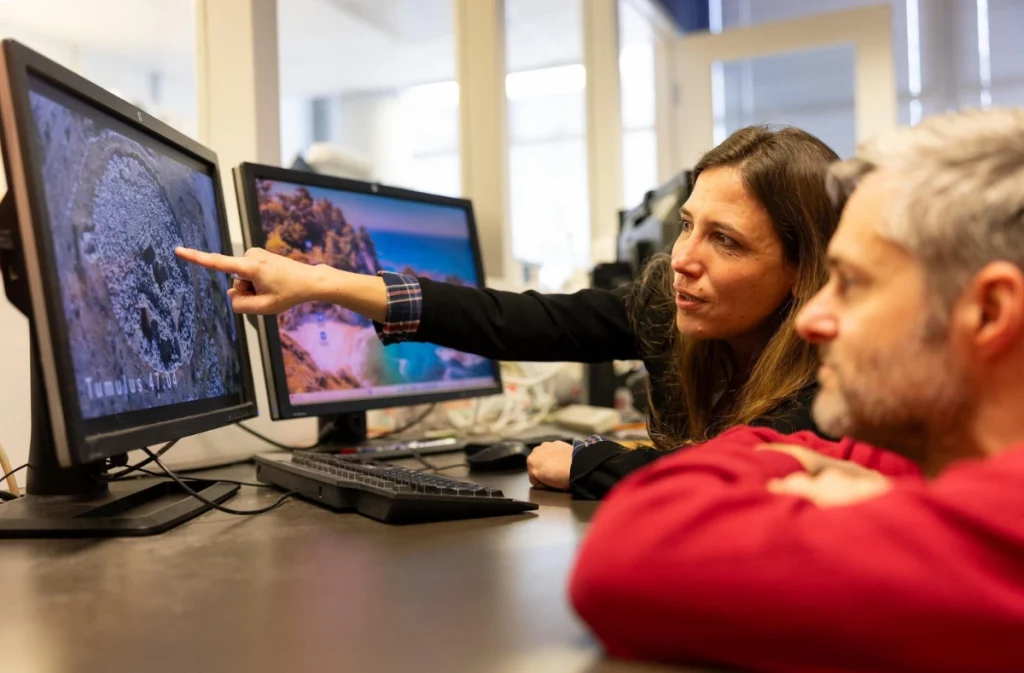

Leading this innovative exploration is Dr. Florence Gaignerot-Driessen, Assistant Professor of Classics at the University of Cincinnati. Alongside an international team of researchers, students, and engineers, she’s using 3D scanning, printing, and clay modeling to decode ancient techniques of mass production and understand the ritual significance of these forgotten icons.

“This is experimental archaeology. We try to reconstruct ancient techniques and practices,” said Gaignerot-Driessen.

Figurines of the People: Mass Production in the Ancient World

Discovered at a site believed to have been settled between 1200 and 650 B.C., these figurines, mostly dating between 900 and 350 B.C., offer compelling evidence of mass production practices long before industrial machinery.

The figurines were not luxury items. Crafted from common clay, they were intentionally modest. Their simplicity points to their accessibility: you didn’t need wealth or status to make a spiritual offering.

Courtesy – Andrew Higley, UC Marketing + Brand

“They had little intrinsic value… they were modest offerings,” Gaignerot-Driessen explained. “So you didn’t need to be a rich or important person to buy your little figurine to deposit.”

Yet, despite their material modesty, these figurines carried significant cultural and emotional weight. They were most likely offered during rites of passage, perhaps marking milestones such as puberty, marriage, or motherhood. Many may have been placed as appeals for divine protection, connecting the material world with the spiritual.

Technology Meets Antiquity: From Clay Shards to 3D Models

To explore how these figurines were made and why they were placed so deliberately, Gaignerot-Driessen teamed up with French researcher Sabine Sorin from the CNRS (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique) and engineers from UC’s College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning (DAAP).

Sorin used GPS, photogrammetry, and lasergrammetry to create 3D simulations of the terrain at Anavlochos. These digital models allow researchers to visualize how the figurines were deposited and how the terrain may have influenced ritual behaviors.

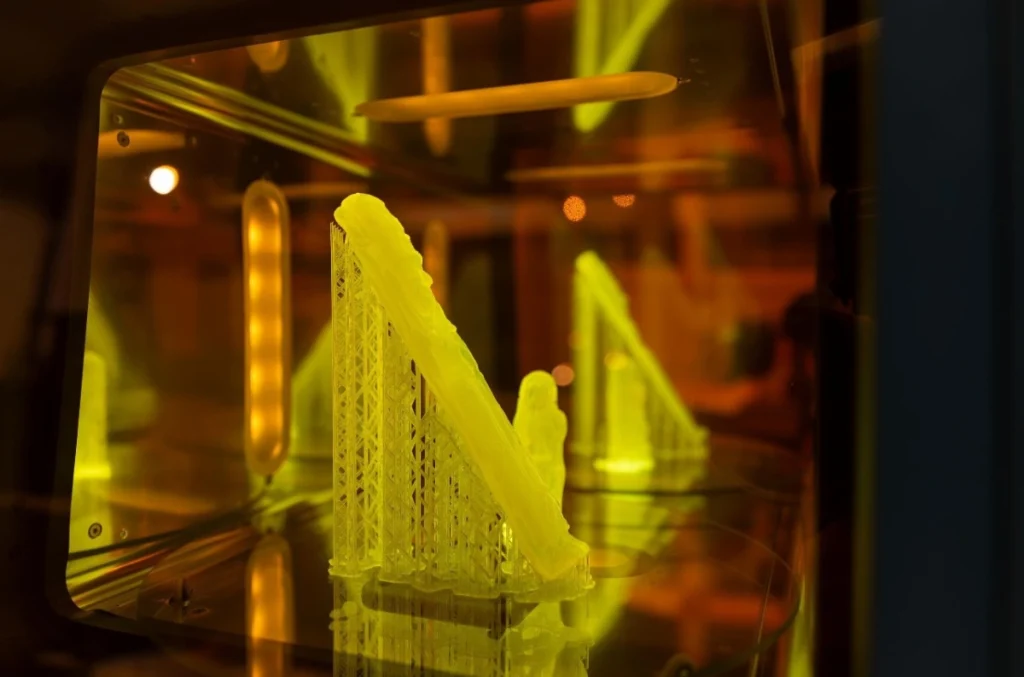

Courtesy – Andrew Higley, UC Marketing + Brand

Meanwhile, at DAAP’s Rapid Prototyping Center, manager Nicholas Germann worked with engineering resins to produce lifelike replicas of the figurines using 3D printers.

“We’re creating a true-to-form artifact that mimics the original in almost every way,” said Germann. “It’s recreating lost techniques of ceramics and revolutionary processes to observe degradation.”

This fusion of ancient and cutting-edge methodologies exemplifies how experimental archaeology can open up new research frontiers, allowing scholars not only to study but to recreate ancient lives and practices.

Rebuilding the Process: Molded vs. Modeled Figurines

In UC’s ceramics lab, Gaignerot-Driessen rolls up her sleeves to explore one of the most compelling questions: Were these figurines made from moulds or modelled by hand?

By creating both types of replicas, one with molds, another modelled manually, she and her team hope to identify microscopic differences in structure, which may reveal the ancient techniques used in mass production. To confirm their hypothesis, they even plan to break the replicas to study their interior composition, just as archaeologists do with the original fragments.

Courtesy – Andrew Higley

“It’s much easier and quicker to use a mold to mass produce these objects,” she explained. “But to prove that this is what the craftsmen have done, the next step is to break the replicas and compare the interior parts.”

Through this hands-on replication, Gaignerot-Driessen is essentially reverse-engineering the manufacturing process of a long-lost ancient industry.

What the Figurines Tell Us About Ancient Greek Society

The figurines offer more than insight into production, they reveal the deeply personal and social dimensions of ancient ritual life. Many of the plaques depict women in elaborate dress, including traditional Greek garments like the epiblema (a cloak) and the polos (a high cylindrical headdress). Some feature mythological figures such as the sphinx, linking the artefacts to wider symbolic or religious networks in the ancient Mediterranean.

Courtesy – Andrew Higley

These stylistic details also reflect Near Eastern influences. In the seventh century B.C., Crete saw a significant influx of imported objects and immigrant craftsmen from the East. The design and iconography of the figurines testify to a cultural melting pot, where foreign artistic traditions fused with local religious practices.

Training the Next Generation of Archaeologists

The Anavlochos project is more than an academic study, it’s a living classroom. Each year, Gaignerot-Driessen brings UC students to Crete to gain real-world fieldwork experience. These students participate in excavations, artefact analysis, and even experimental reconstructions using locally sourced clay.

Courtesy – Andrew Higley

They also engage in ongoing investigations into ancient burial sites, sanctuaries, and settlement remains, helping to shed light on how people lived, worshipped, and interacted with their environment.

The Future of Ancient Research Is Multidisciplinary

The collaboration between classics scholars, ceramic artists, digital engineers, and students marks a bold new direction in archaeological research. Projects like this underscore how interdisciplinary partnerships can revive long-buried histories, not just through texts and translations, but through touchable, testable reconstructions.

“This project brings together ancient and cutting-edge methods,” said Germann. “It’s absolutely amazing.”

From the clay of ancient Crete to the synthetic resins of a Cincinnati lab, The Ladies of Anavlochos are reemerging—not just as artefacts, but as active agents in a dialogue across time, helping us understand the evolution of technology, belief, and human creativity.

Image Courtesy – Andrew Higley

Contributor