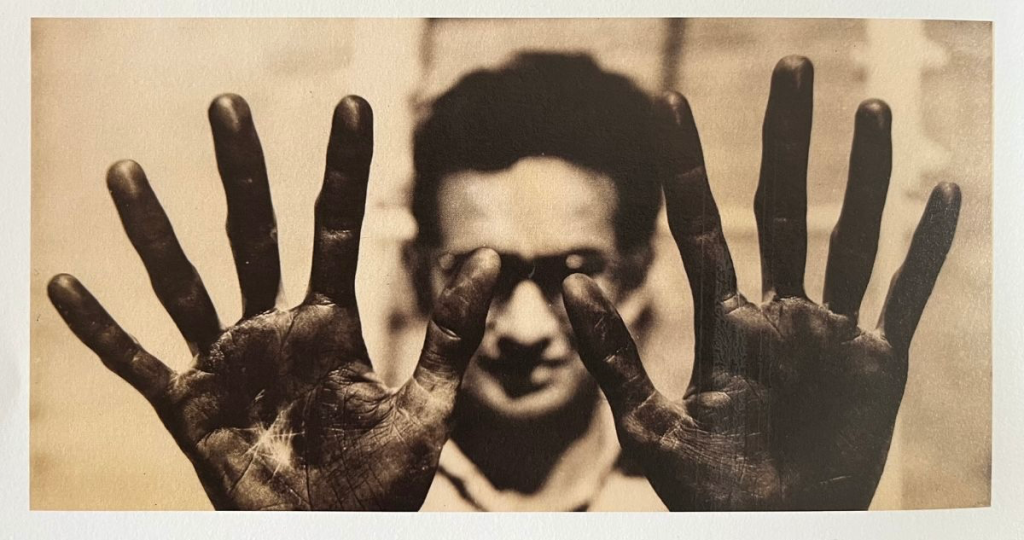

By Archana Khare-Ghose

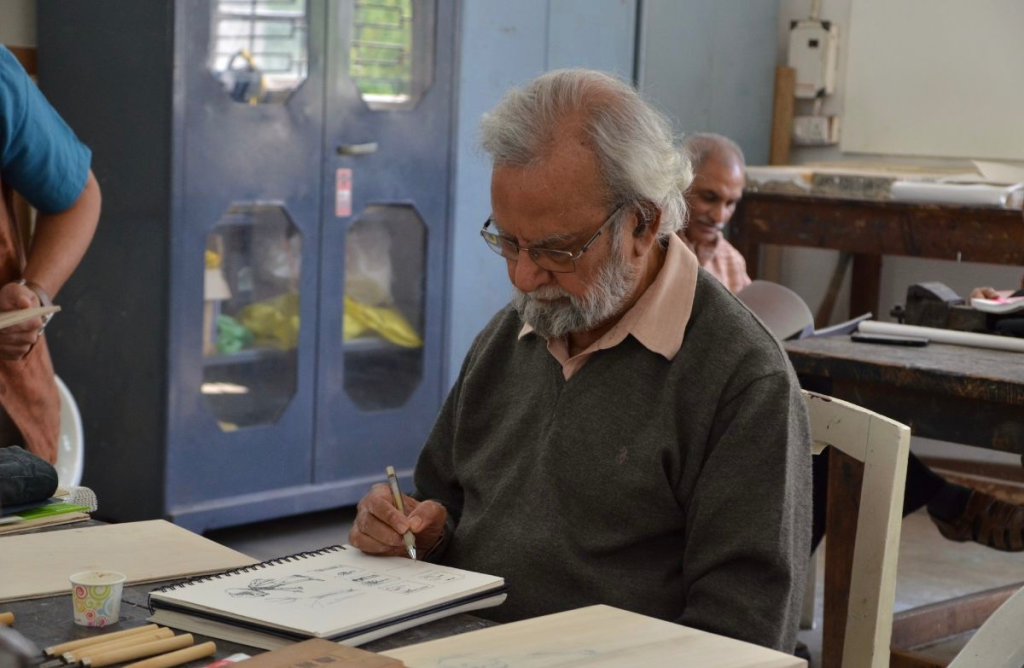

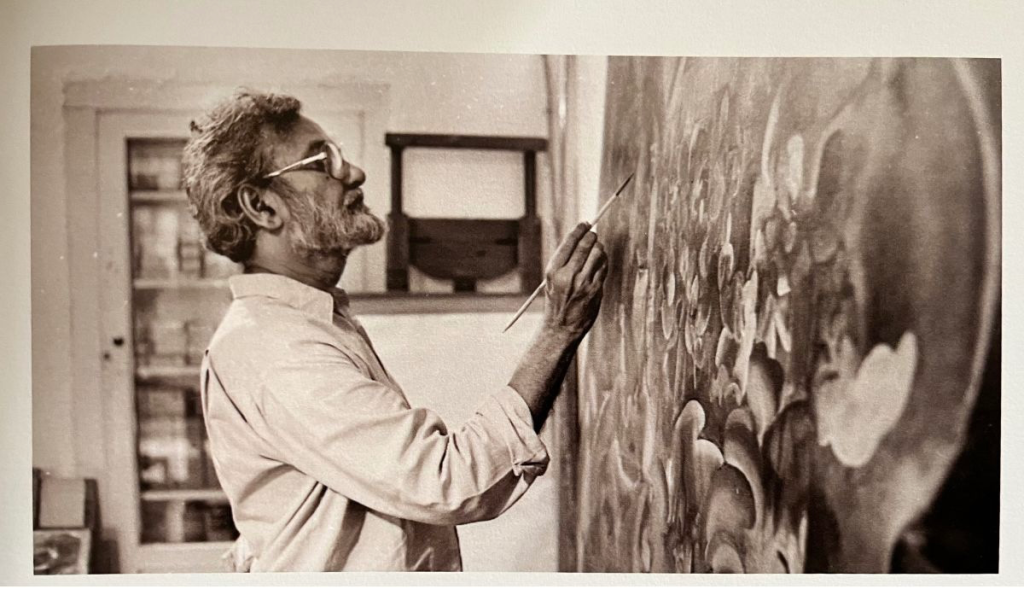

Any introduction of Gulammohammed Sheikh lays equal emphasis on his identity as an artist and a poet and writer. Despite this equally weighted description, his identity as an artist often overshadows his accomplishments with the pen. That could be due to various reasons, primarily a result of the strong visual aspect of the former. Yet, his written output, especially his criticism of Indian art, published throughout his career in prestigious publications such as Marg, national and state Lalit Kala Akademi journals and monographs, newspapers, other independent journals as well as in books, in itself makes a very substantial body of writing in Indian art, rather special and rare because it comes from the pen of a practicing artist.

The most important service his writing has rendered is in making a serious attempt at democratising art writing in India, which remains disproportionately tilted towards English. His 2017 book in Gujarati, Nirkhe te Nazar, for example, remains a rare compendium on the most current trends and concerns of art in a regional language. While in the past two interviews with Abir Pothi, the veteran artist discussed his life and concerns as a painter, in this instalment he speaks on his career as a writer, which due to time constraints left us wanting for more.

Excerpts:

You belong to a generation of artists in which quite a few of them were strong writers as well—more specifically, writers with a voice. What was it that so many important artists of your generation became known as writers—was it their personal agency alone, or was there some catalyst in those times? Why can such parallels not be found in contemporary times?

First of all, in the history of contemporary or modern Indian art, painters were also writers. For example, Rabindranath Tagore was first and foremost a writer, he began painting at a late stage. Similarly, Abanindranath Tagore, Nandalal Bose, Benode Bihari Mukherjee, Amrita Sher-Gil, Jagdish Swaminathan, and Gieve Patel, to name a few, were all prolific writers along with being painters. Swaminathan even wrote poetry. So, writing is not something unusual that happened to me alone. It is something that came together, from early times. Vallabh Shankar Rawal, one of my school teachers, played a role. Though he was my teacher, later we became good friends. He introduced me to Sanskrit meters in which we used to write poetry, which was used by many Gujarati poets too. It was comparatively simpler to write songs than poetry. When I came to Baroda [to study at MS University, 1959-63], I was introduced to the world of literature by Suresh Joshi. He was my literary mentor. I worked with him for several years, even made art for his magazine, Kshitij. Suresh Joshi introduced me to world literature, especially the verse of Austrian poet, Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926). In Surendranagar, where I grew up, I had not read any of this. So, it was a new and thrilling experience for me.

I began to browse through a great variety of writing, including poetry. There was something unusual, indeed, about great poetry, which I gradually realised. I had the advantage of learning English and great poetry, so I decided to leave both the metres and Sanskrit. I gave up metres used in making a song and instead started writing in free verse.

I started writing a lot, using the usual language, as well as the language used by the people. I was quite involved and very passionate about it. Some of my poems were even published. My poems appeared in some literary journals such as Kshitij, Vishwa Manav, and others. Usually, there were very few takers for poems. As far as decline in writing by artists today is concerned, I don’t think we should ask them to write if they don’t wish to. They should have that choice. Prabhakar Barwe and Swaminathan, who were my contemporaries, were writers. Barwe’s Kora Canvas [in Marathi, since translated] is well known. Swaminathan wrote well in Hindi. Even my mentor, K G Subramanyan published poems. Today, Atul Dodiya, sometimes tries his hand at writing; but there are some of his writings that I may not know about.

Could you share a moment from your life when you had to pay for what your wrote? How did you cope with that situation, and what the response of the art fraternity to you at that moment?

I don’t think my painting or writing created such an impact [for me to pay a price]. When my poems were first published, orthodox literary critics were taken aback. They criticised it strongly but it didn’t matter to me. I continued to write what I had to. Throughout my life, I have done what I thought I should be doing, not at the behest of somebody else. My decision to use free verse, to use imagery, was mine and it was beautiful as well as worldly. I respond equally to beautiful things as I do to pain and suffering.

Why do you think we don’t have art criticism in the country any more save for some rare examples? How does it impact the production of art, without an active atmosphere where ideas can be critiqued in good faith?

There used to be reviews of exhibitions on a regular basis, especially in the Times of India, when poets like Nissim Ezekiel wrote. Gieve Patel too wrote about the exhibitions that he saw, it continued for some time. Even other newspapers published similar things, not necessarily regularly. Art criticism is a specialistion that can only be understood in terms of what the business of art criticism is. A good art critic, while they examine and investigate, they may agree or disagree with the artist’s image too. They put it in an article in the manner of an argument. That is different from regular write-ups in newspapers. Art criticism is a different ball game altogether. The well-known art critic Richard Bartholomew wrote about the first generation of Indian artists such as M. F. Husain and S. H. Raza, to name a few, but he also wrote for our generation. He wrote my catalogue too. He regularly wrote in the Thought magazine. Though he would meander sometimes, he wrote wonderful pieces; but, not all of it is criticism. You see, criticism is often rather wrongly understood, it is not putting down the artist. You look at the works, you analyse, whether it has been created with an effect that pushes the journey of the artist forward… and so on. Keshav Malik in Delhi and Nissim Ezekiel in Mumbai were two of the greatest art critics of India. Geeta Kapur is the only one now. Art criticism has also developed and evolved over the years, in the sense that the touch is lost, sometimes it becomes a free prose. There are many genres in which art writers write now.

Featuring Image Courtesy: Hindustan Times

Archana Khare-Ghose is a senior arts journalist, and a commentator on art, market, books, society and more