How fashion has changed as women’s rights advanced, and what the future holds.

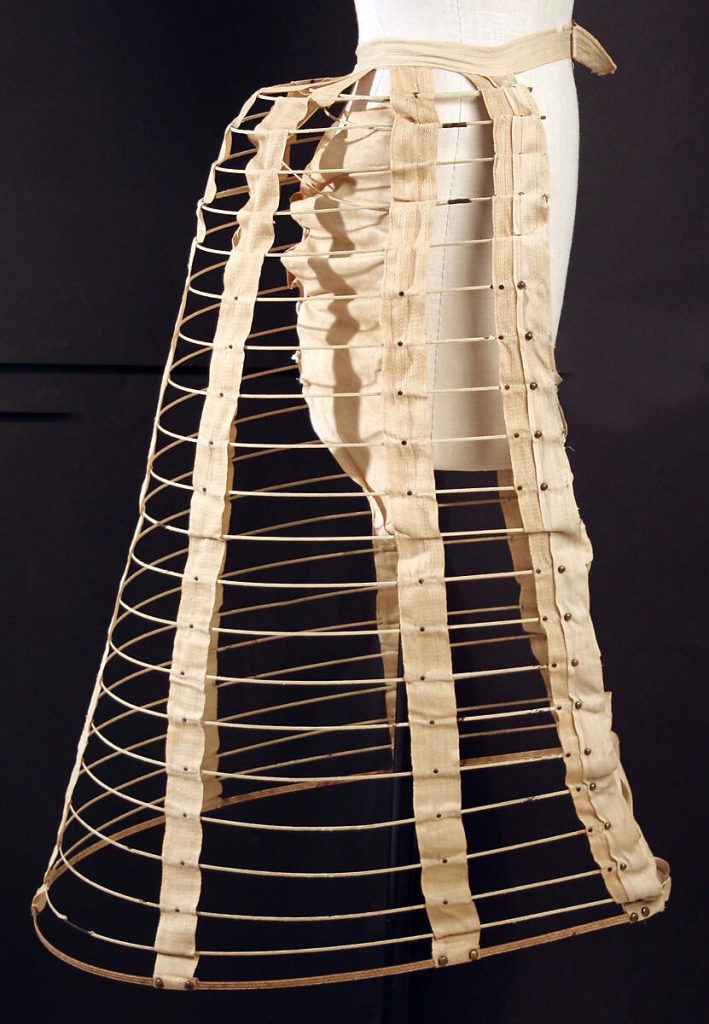

Back in the Victorian era, affluent women’s fashion consisted of corsets, crinolines and bustles. Corsets were tightly laced to achieve a tiny waist, cage crinolines were made of horsehair, or in some cases even whale-bone so that the skirt over it can appear as voluptuous as possible, and bustles which later replaced crinolines as a sort of belt which made the skirt appear fuller. It is safe to assume that women must have felt a little uncomfortable to say the least. When women began to campaign for suffrage, education, moral purity and temperance (i.e little or no consumption of alcohol) they demanded that their fashion follow suit. And thus, was born the Victorian Dress Reform Movement, also known as the Rational Dress Movement.

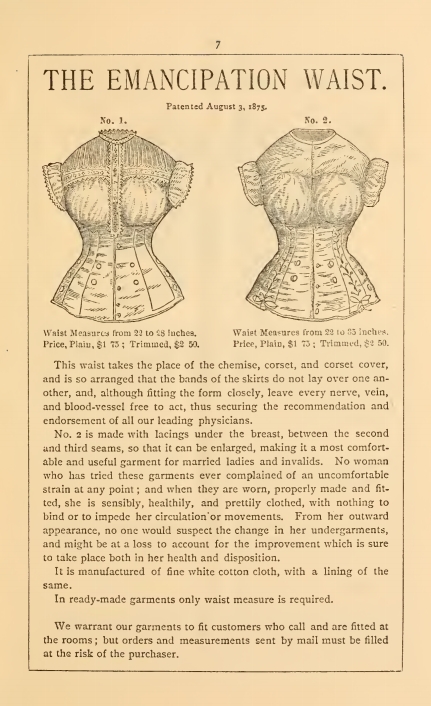

Corsets and tight-lacing were uncomfortable enough to warrant an entire controversy on their own, termed The Corset Controversy. Even the political philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau who was a key influence in the French Revolution was vehemently opposed to tight-lacing, calling it “an enemy to mankind.” Women had varied opinions, with one article in the Chicago Tribune being titled “THE SLAVES OF FASHION, through Long Centuries Women Have Obeyed Her Whims.” Many women however were in favour of tight-lacing. “I myself have never felt any ill effects from nearly 30 years of the most severe tight lacing” said one letter to the Boston Globe. It was when doctors began to express concerns over the negative health effects of corsets and tight-lacing, such as miscarriages and digestive issues, that the sentiment against corsets grew. It was namely due to how the proper fashions restricted movement and comfort which was a great hindrance for now working women as they took more space in the political and public arena. American women who were involved in public speaking for anti-slavery movements, put forward the demands for more practical clothing that didn’t restrict their movement. Instead of corsets and tight-lacing, garments such as “emancipation waists” and bloomer suits were suggested, however, they wouldn’t be long-lasting trends until bloomer suits would be recycled as women’s athletic-wear from 1890s-1900s.

The calls for loose, more comfortable clothing weren’t merely due to health, politics or practicality, but aesthetics and fashion themselves as well. The Artistic Dress movement favoured long-flowing, plain and relatively loosely-fitted gowns, for a purely aesthetic reason. Painters such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti respected the “old masters” of the middle ages, and hence preferred simpler dresses. The wives and models of said painters began to use these garments as everyday wear. By the 1860s, the more intellectually and artistically inclined folk preferred The Artistic Dress. The Aesthetic Dress in many ways was the successor of The Artistic Dress, and carried many of its traits, such as a preference for beautiful fabrics, simplicity of line and rejection of tight-lacing. However, the Aesthetes rejected the ideas of the aforementioned Victorian Dress Reformers, as they believed that the arts, including fashion, should merely be beautiful, and exist for sensuous pleasure. Designer Ada Nettleship was at the front of both the Aesthetic Dress and the Rational Dress movement. The Victorian Dress Reform Movement didn’t achieve widespread change, however, into the 1920s as World War I occurred, women’s suffrage was granted and women had more opportunities in career and education. It brought along an organic relaxation of clothing for women. The “New Woman” now wore skirt suits, ties, trousers and other garments inspired by masculine fashion, and society had comparatively relaxed to the idea of women donning “masculine” garments for casual activities and sports

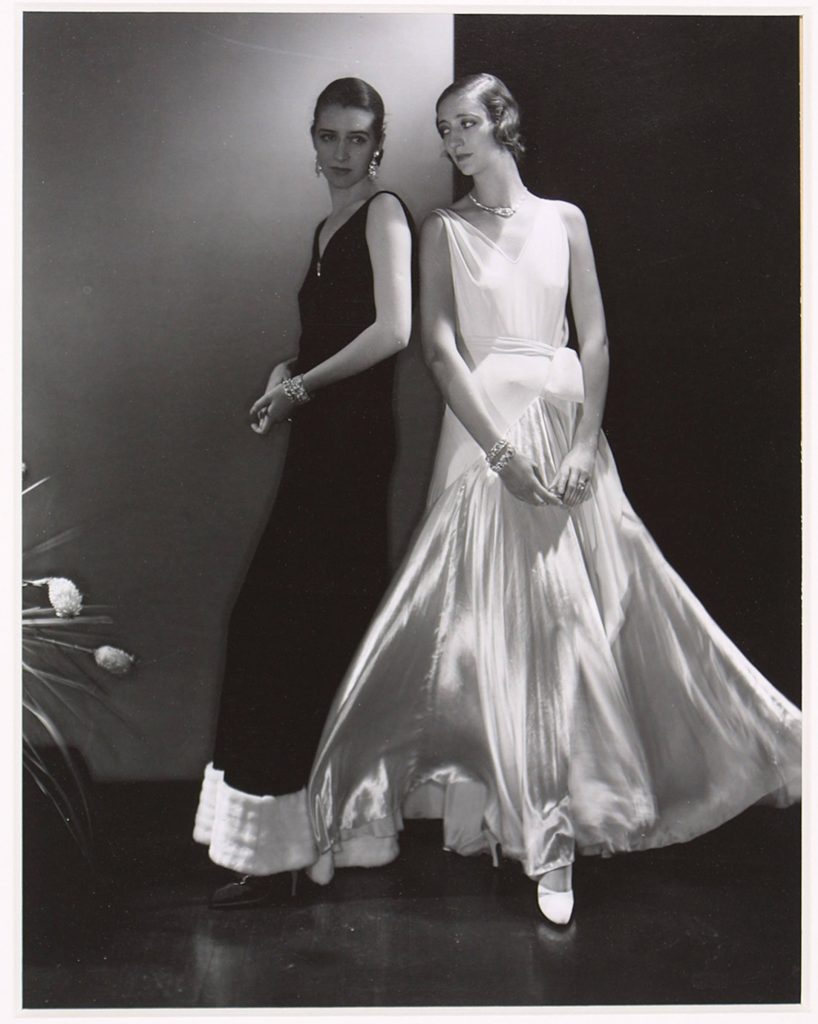

Designers such as Coco Chanel and Madeleine Vionnet would further the move to loose, softer and simple clothing. Vionnet was inspired by the dances of Isadora Duncan, who pioneered modern dance as her dances were less rigid and more free-flowing than classical ballet. Duncan and Vionnet were both inspired by Greek art in their own respective fields. Vionnet’s most identifiable contribution to the world of fashion was the uninhibited use of the bias-cut, which allowed for the dress to fit the wearer and highlight their natural shape and also allowed the dress to move freely around the body.

In Japan, Utako Shimoda, a women’s rights activist and educator, found both the Kimono and the western corsets too restrictive. From her time serving as a lady-in-waiting to Empress Shoken, she created a uniform called the hakama for the Jissen Women’s University. The Hakama followed as school uniforms into the Meiji (1868-1912) and Taisho (1912-1926) periods.

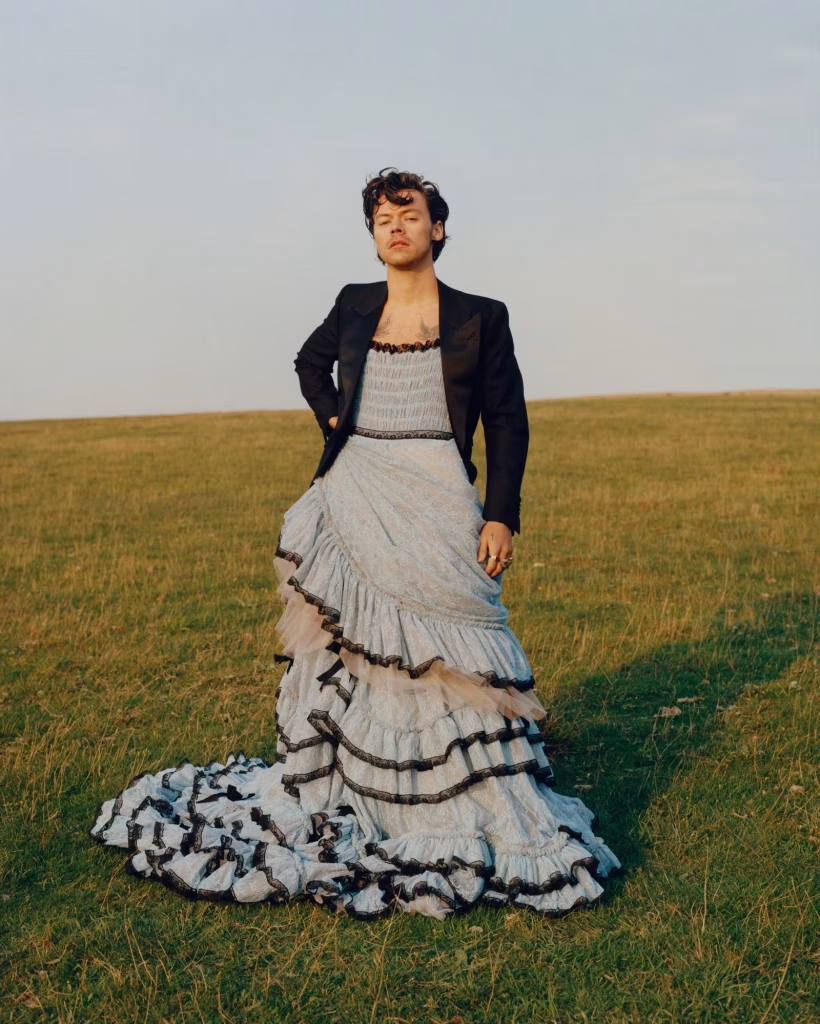

We live in times with a greater amount of personal liberty and freedom for women, and hence, whether we prefer to wear a corset, a sari or joggers, we have the options. However, keeping recent discourses in mind where stepping outside the conventions of the gender binary is slowly gaining more acceptance (save for some outrage over Harry Styles wearing a dress), and the idea of dress code itself is being called into question for being sexist, what changes in all fashion are in store for us in the future? Will future generations look at bras the way we look at corsets? Could it be that the idea of “formal-wear” at all might vanish, and that it could be perfectly acceptable to come to work in joggers? And how will the lines between “men’s” and “women’s” clothing blur? It might just be that all clothing will clothing for everyone, and the term unisex will be completely redundant.

References

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victorian_dress_reform

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corset_controversy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artistic_Dress

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madeleine_Vionnet

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corset_controversy

Citizen of The World. A musician, artist and writer. Social media manager at Abir Pothi