How Mario Miranda inked everyday chaos with wit and warmth

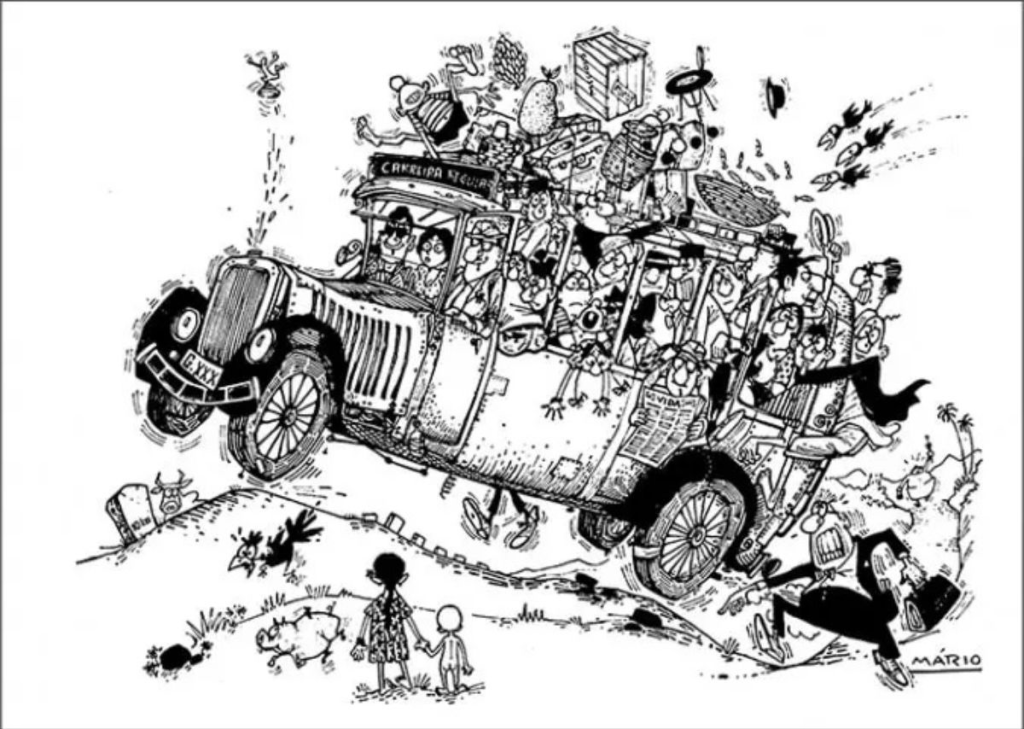

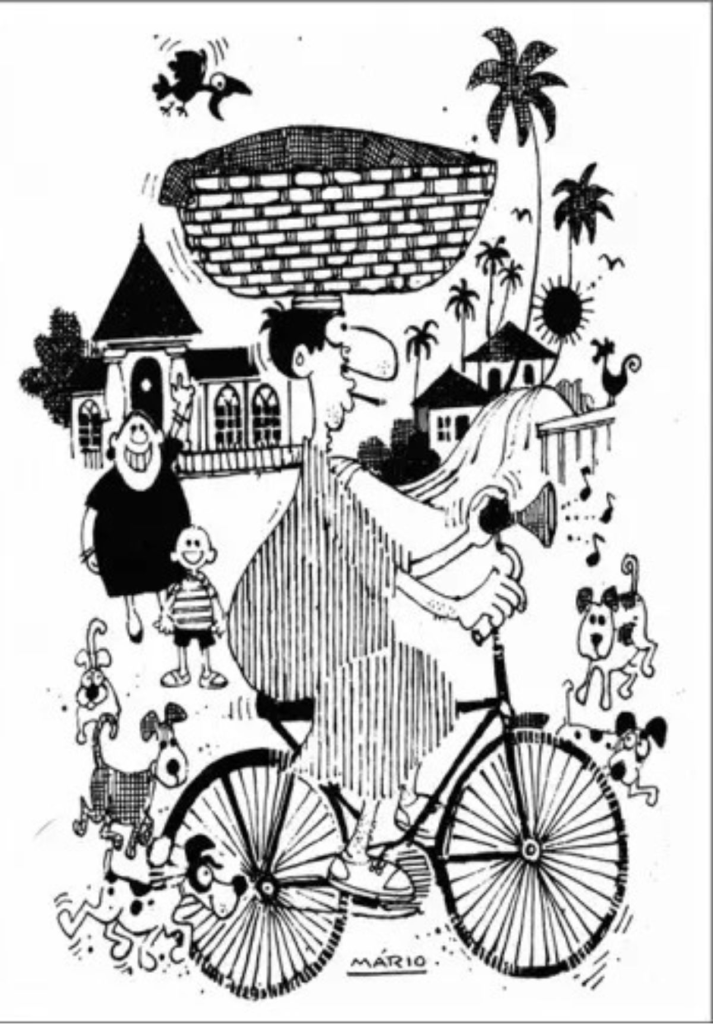

When I think of Mario Miranda as a journalist first, I am bound to consider the fact that without the hustle and bustle of Bombay, Mario would not have become what he is. Many of the characters imagined by him through caricature carry healthy dollops of Bombay within them. The meteoric madness of Mumbai (as it was then) and the unmistakable, leisurely chutzpah of Goa mingled to give us many of the ‘people’ that populate Mario’s world.

The arc of Miranda’s own story probably infused the joie de vivre into his work. His quiet but furious need for freedom was evident from an early age.

He was born in Daman during the Portuguese rule of Goa and was therefore a Portuguese citizen until 1961. He became Indian after the liberation of Goa.

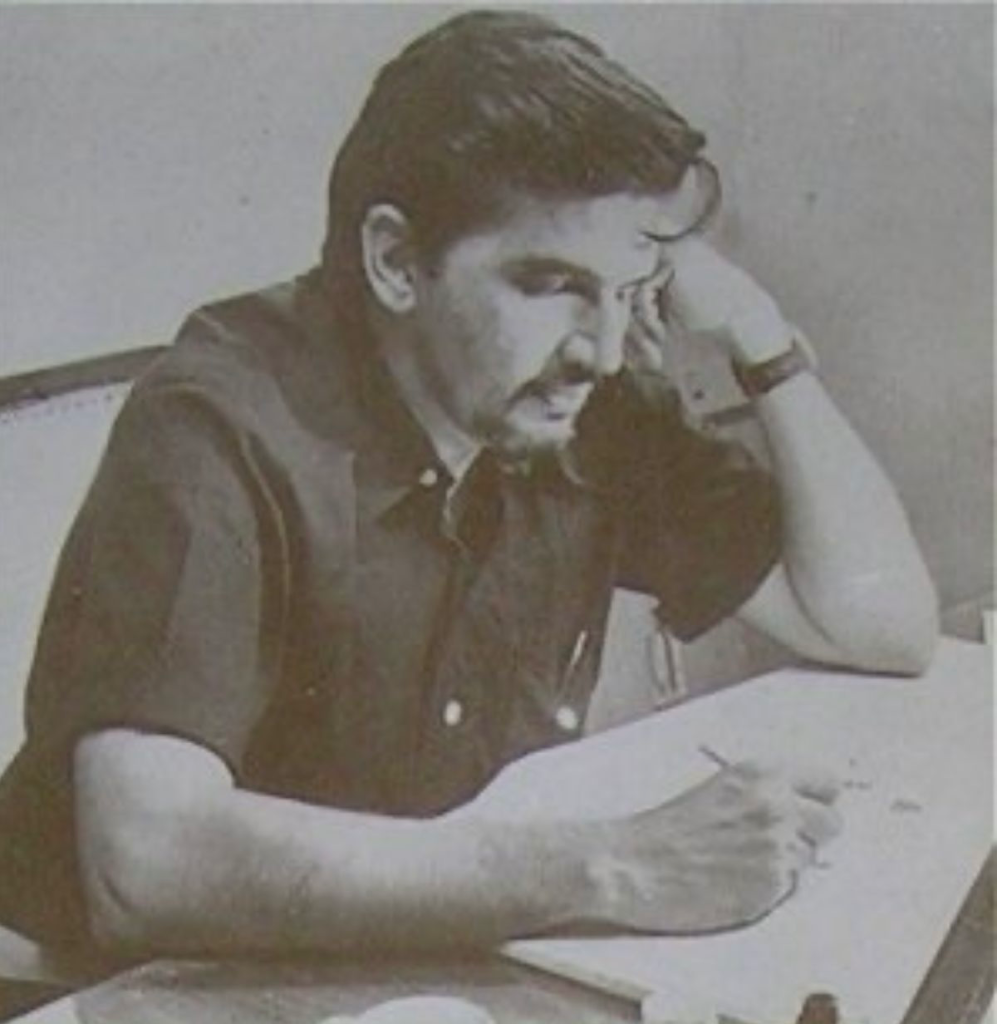

He began drawing as a child, and it was his mother who helped him move from the house walls to a notebook. His talent was precocious without a doubt—but so was his recognition of that gift. He made caricatures for family and friends, charging a token amount in return for a keepsake from his unique world. Like any cartoonist worth his salt, he rubbed a few people the wrong way even as a student, especially for making caricatures of Catholic priests in his school. He also maintained drawing diaries from the time he was about ten years old. While it was not expressly vocalised, cartooning had chosen him as one of its own. It was to become his career.

After schooling at St. Joseph’s Boys’ High School, he went on to study History at St. Xavier’s in Mumbai, where he obtained a BA degree. After this, like many even today, he studied Architecture because his parents wanted him to. True to form, he found Architecture drab, and soon his interest fizzled out. Meanwhile, he began getting small commissions to make drawings. It’s worth noting that he even prepared for the notoriously difficult Indian Administrative Services exam in his early years—but we must thank our lucky stars that he instead decided to lampoon the bureaucracy.

His skills as a cartoonist and his exceptional drawings led him through a career with many crests. He travelled the globe and even met Peanuts creator Charles Schulz. His drawings found their way into magazines like Mad and Punch. As the saying goes, there was no looking back after his big break in 1974, when he went to America on an invitation from the United States Information Services. He would go on to exhibit his art in over 22 countries in a career spanning many decades.

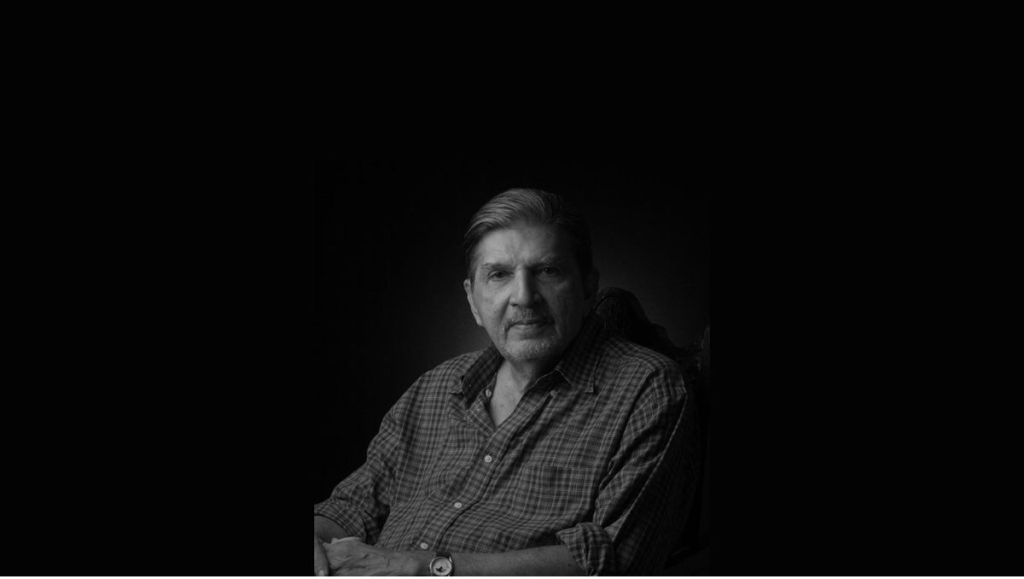

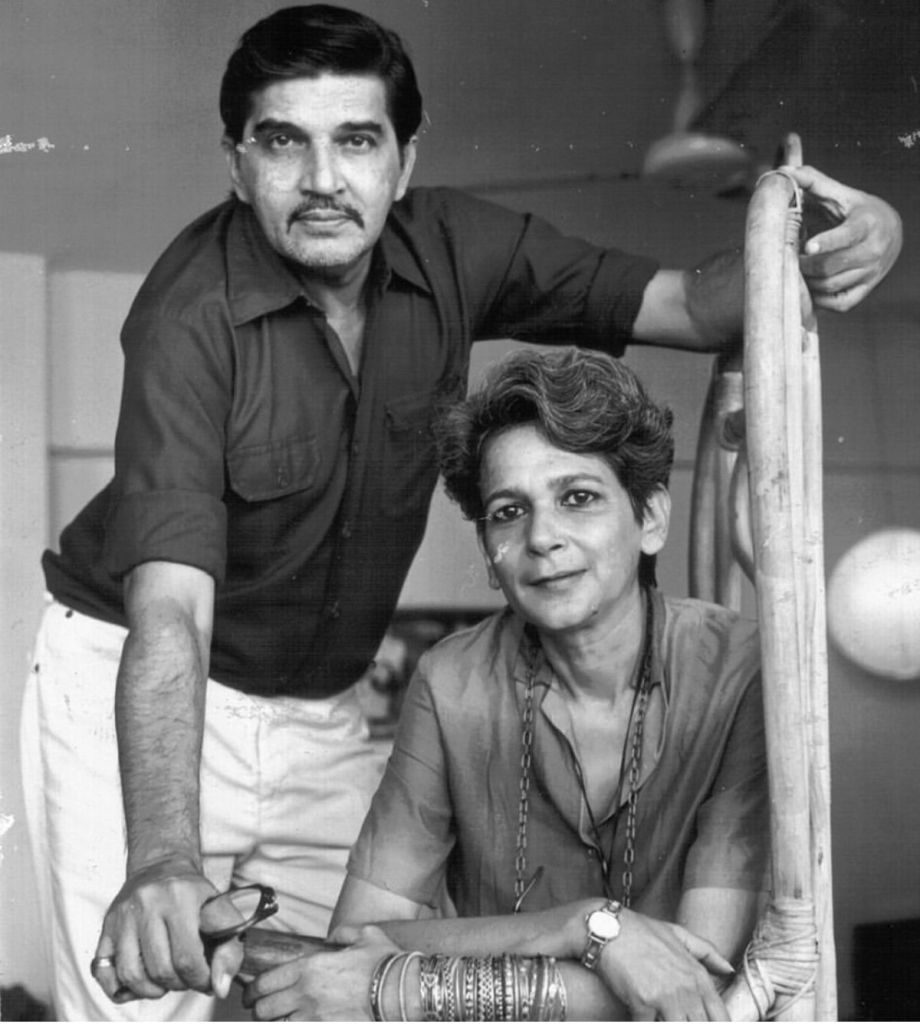

The Goan boy eventually settled down with his wife Habiba in the picturesque village of Loutolim in Goa and lived there till his death at the age of 85. Forever the iconoclast, he was cremated at a Hindu crematorium in Margao, as per his wishes. Needless to say, Mario was larger than life.

What I discovered later was that, from a technical standpoint, Mario was a thorough individualist. He gave up using the brush for his cartoons and instead used a fountain pen. Pen and ink were his chosen medium. The nib was his weapon of choice.

The certainty inherent in his drawing was what first drew me to him. His lines, in various moods but always bold and confident, formed the foundation of his art. Not one gesture seemed extraneous or unintended. Through this highly self-contained style, he created a carnival of mischief. In almost all of his ‘busy’ drawings, you could see the story play out in real time. You knew which big-lipped belle was enamoured with which lothario, which aunty was peeved by which uncle, who wanted to dance with whom, who was clueless, who was suffused with envy, who was gladder than glad—and yes, who was drunk out of their wits.

This same play of humanness was also visible in his truly charming and funny caricatural essays of the dogs that inhabit every village of Goa and every street of India. Mario’s world was a joyful one, despite the bedlam and squalor that never fail to annoy us in this mad rush called India.

I particularly liked some of the Goan fisherwomen he drew. I liked them because their demeanour says you simply cannot mess with them. They aren’t just selling fish; they are making a statement. Nothing says “the personal is political” better than a Goan fisherwoman tired and sick of the daily rigmarole she must endure just to sell a few bhangdas and surmais. She is sexy in a nonchalant way—but you dare not call her sexy. Even if you bought her whole basket of fish, all you’d get is a story of how tomorrow will be even tougher.

In fact, I once met a fisherwoman in Saligao who had such magnetic charm that a friend of mine would go to her just to talk. He didn’t even like fish that much.

Mario’s cartoons have now spilled over into Goan culture. They’ve become part of the popular folklore—the everyday imagination. Many use this stereotype to sell Goa to the world, while a small minority feels that’s not the only image Goa should be known for.

It is safe to say that Mario’s world is complete. It is a philosophy in itself—loved by many, with a few detractors. Rarely does anyone hold a neutral view of his work.

For many of us navigating the art world, a question often pops up: Are Mario’s caricatures high art? My answer is—if Basquiat’s skull is high art, Mario is no less. Just that Mario didn’t communicate through huge canvases.

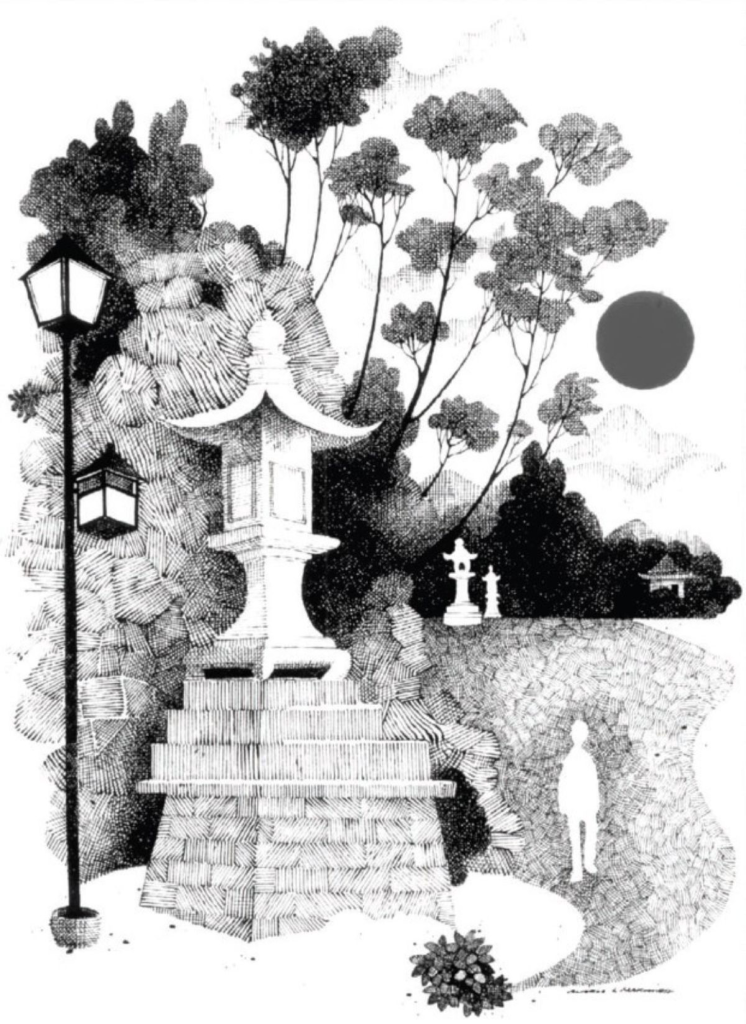

Personally, I find his “non-caricatural” drawings of Goan houses and landscapes invigorating. They are precise and beautiful—a different kind of Mario. While they may not have the Zen-like quality of a Chinese or Japanese ink-on-rice-paper landscape, they have that distinct taste of coconut and palm vinegar. They are a true echo of Goa. They may not fall in the same category as a meditative piece from Gaitonde, but they possess all the skill and values of a master draughtsman and a keen observer of human nature.

Mario is special because he is deep and shallow at the same time, fun and tragic at once. Most importantly, he is never boring. He gave us perfect stereotypes to fall back on and laugh at ourselves.

Personally, I love Mario’s power in the way he capturess human situations perfectly.

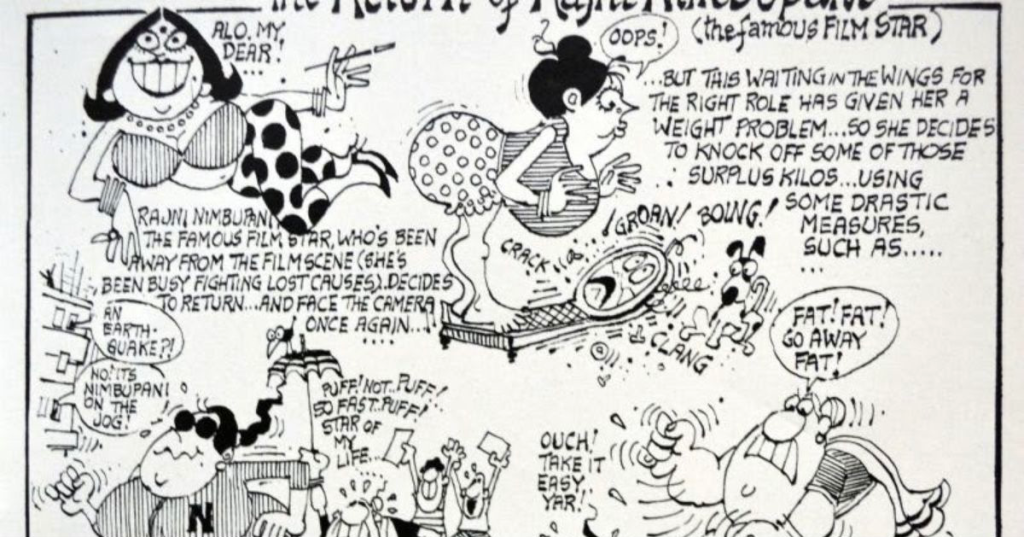

Think of Ms. Rajani Nimbupani.

She struts like a cocktail in stilettos, dripping drama and lime juice. Her eyes roll faster than rickshaw meters—always judging, never blinking. Men fear her sharp tongue more than their wives’ silence. She is decidedly uninterested in intellectual pursuits and loves the red carpet. She is the perfect Page 3 Bollywood archetype—an unfailing image that will last a long, long time.

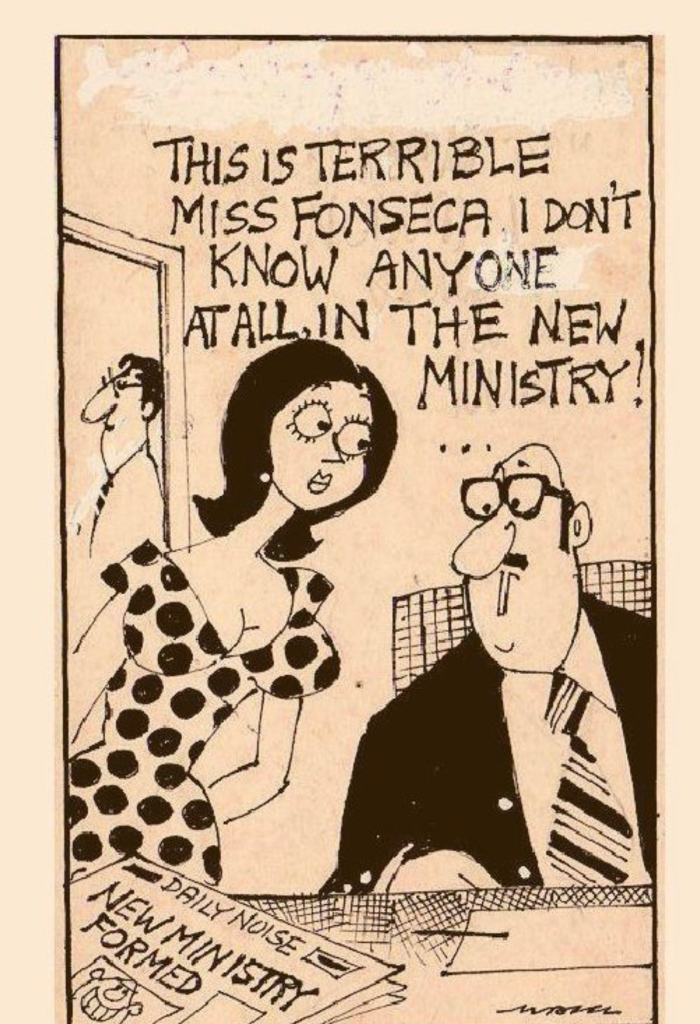

Ms. Fonseca is everywhere. She enters with hips that cause traffic jams. Perfume, gossip, and mild chaos trail behind her like obedient pets. Every office-goer turns to look; every woman pretends not to. She’s not a person, she’s punctuation in a dull sentence. As a secretary, her abilities are, well, secretarial. As an individual, she is second only to herself.

Bandaldass, the politician, is another case in point. A man of many files and few decisions, he survives by nodding in meetings he doesn’t understand. He is a reflection of Mario’s opinion of politics.

The nameless Boss is another archetype—a portrait of the boss we don’t really like. With eyebrows arched like audit questions, he rules from behind a desk cluttered with delusions. Every sentence he utters feels like a memo of mid-life crisis. He measures productivity in sighs and postponed vacations.

In Mario’s world, you’ll meet not only these characters, but many others—some of whom sit on the great Goan balcão, observing the world and offering definitive opinions on why it’s no longer what it used to be.

Mario isn’t just a Goan. He is a man who saw through mankind in an affectionate, funny way. Not to hurt—but to hug.

Featuring Image Courtesy: Oscar de Noronha

Former Editor at Abir Pothi