Abbas A Malakar

Vishnu’s avatar Narasimha tears apart the demon king Hiranyakashyap over the knee. Hanuman rips his own chest to show Rama and Sita forever situated with himself. A woman seductively prepares a betel-leaf for. A cat admires all of it from afar with a fish in its mouth. Yes, one of those famous cats.

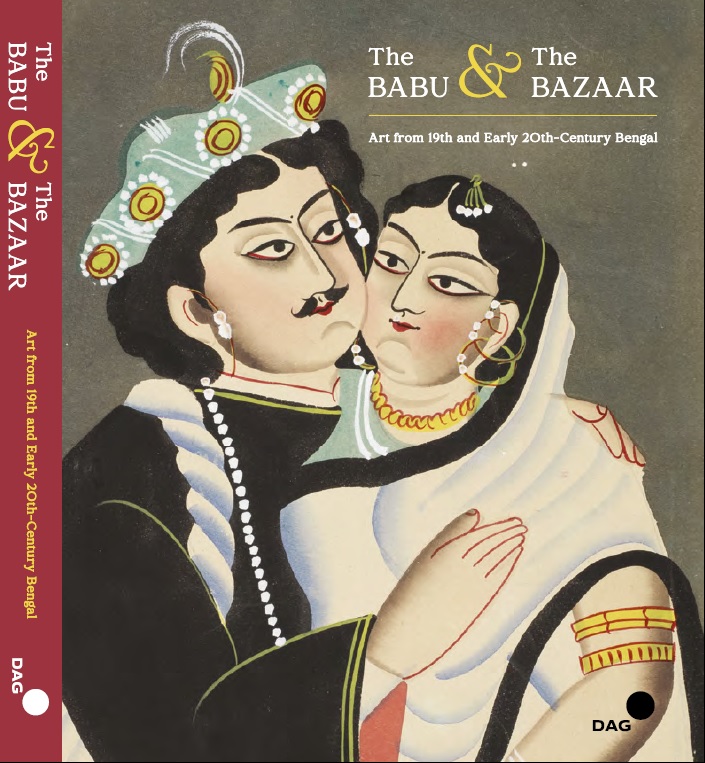

These are the vibrant, irreverent images that greet visitors to The Babu and the Bazaar, Delhi Art Gallery’s latest show in collaboration with the Alipore Museum. The exhibition examines 19th-century Calcutta’s visual culture through three art forms: Kalighat watercolour paintings (pats), mass-produced prints, and commissioned oil paintings. Its fourth iteration after being shown in Delhi, Mumbai and Ahmedabad, and a first time in Kolkata, is a masterpiece in historical exploration, and storytelling. If I have one criticism for DAG, it is this: Bengal needs these exhibitions to be larger and more frequent.

The Kalighat patuas, or pat painters, emerged as largely anonymous artisans who likely migrated to Calcutta from the surrounding villages of Bengal. Their paintings predominantly celebrated divine iconography, bringing to life the fierce Kali of the Kalighat Kali temple, the resplendent Durga, Jagaddhatri, Shiva, Vishnu, and a pantheon of other deities, but gradually grew to include a vast array of subject matters with the growth of their popularity, and markets in the city. Their works were then created for a diverse audience, sold to pilgrims and tourists at the temple bazaar, and prints distributed through city markets using evolving printing technologies (woodcuts, lithographs, oleographs).

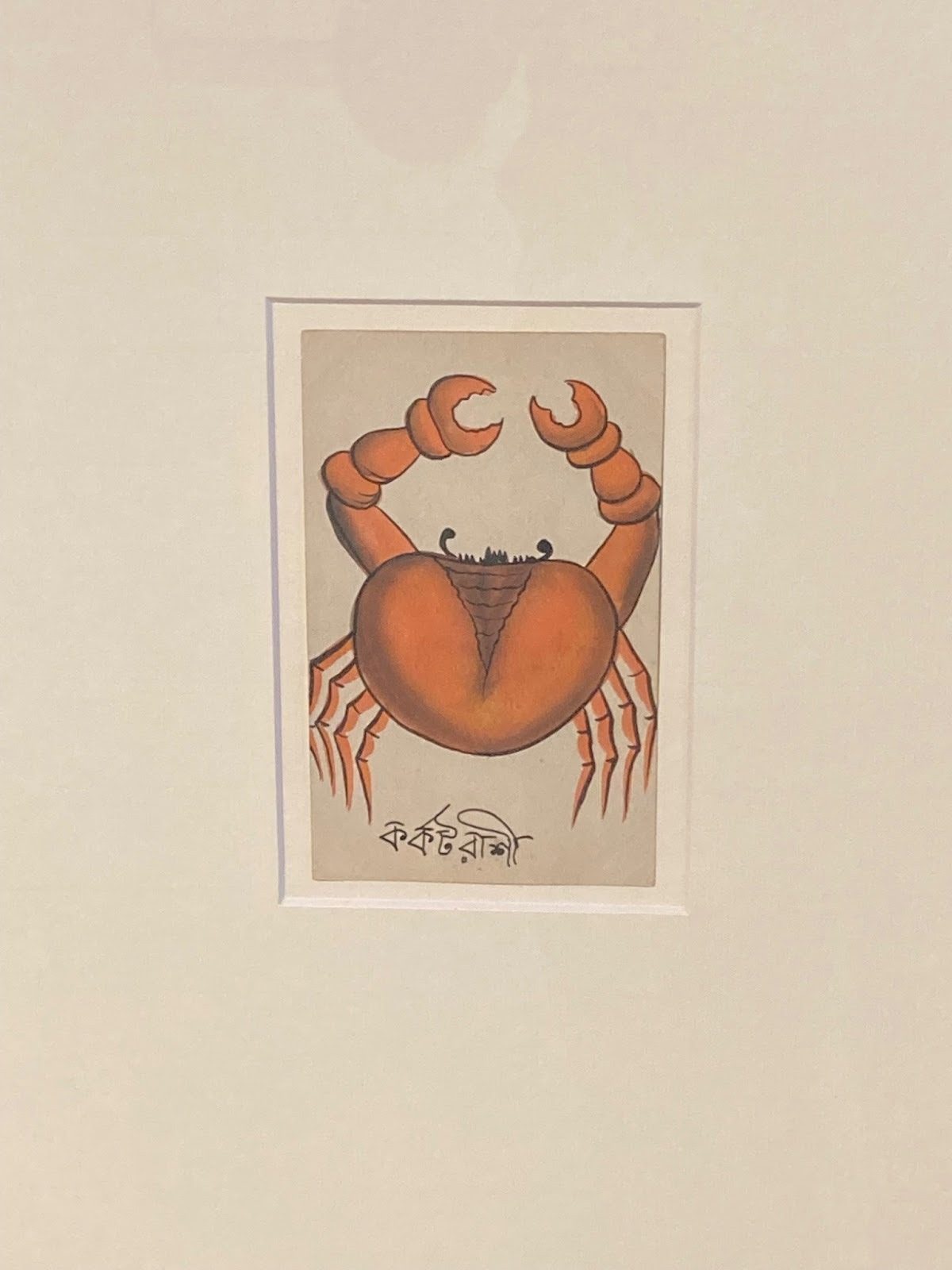

There are some images that are bound to stand out as exceptionally detailed renderings while there are those that shock with their unadorned elegance. One that stood out in this regard was a postcard sized painting of the astrological symbol Cancer, or as the Bengali writing underneath marked it: korkot rashi (crab zodiac); in essence, however, beyond its weight as a zodiac sign, it is just a red crab: effortless, undemanding, and devoid of any pretence.

This expansive set of visuals exploring so many different mediums is a representative of a moment in India’s history where traditions are colliding with colonial enforcements. The century in question between 1830 and 1930 when pat paintings in Kalighat rose to its heights and then vanished, is also the century when the British powers sought to reorient the subcontinent’s arts and largely all education in the fashion of Western Civilization.

A distinctive genre of indigenous oil painting had also flourished across Bengal, catering exclusively to wealthier clients. These works were considered ‘high’ art for their invocation of the divine and alignment with colonial teachings. Despite the different formats and clientele, all of these art forms often depicted similar subjects and iconography, competing for the same market while reflecting distinct aesthetic sensibilities.

But these aesthetic differences weren’t merely artistic choices—they reflected deeper social fractures. The show reveals, and comments on, the cultural divide between colonial Calcutta’s masses and its affluent, English-educated class (babus/bhadralok), who viewed each other with mutual disdain. By comparing religious and secular imagery across these genres, it explores themes of tradition versus modernity, class tensions, and social hierarchies. The babus are the emergent middle class in this period, obsessed with certain luxuries they associate with their reference groups. These reference groups are not only the upper class of zamindars but also the British rulers—both oppressors. Some of the secular images during this time was a satire directed at this class of people, making fun of their decadent lifestyles and sexual proclivities. One of DAG’s earlier press releases gets at the core of this conflict, identifying the babus as being seen then as “deracinated man unaware of worldly problems.”

Bengali society is at this point struggling with far larger problems in understanding of its new structures in education, politics, social norms, and religious or rather the secular freedoms. Within all of this, there was as much positive development as there was cruelty, abuse, and perversion of a system trying to cope with radical changes. This exhibition recognizes many aspects of social change and how they were recognized and represented in the arts of the time, such as in the sundari paintings on display. Primarily erotic representations of women, inclined towards sexually charged symbolism, the wall label mentions how their dresses are the widow’s white saree, pointing to how widows were increasingly being pushed towards prostitution.

These darker undercurrents run throughout the exhibition, though they’re just one thread in a much larger tapestry. There is so much to explore in the show, and so much being hinted at. This spectrum includes rivalries between different studios and their variations of similar subjects, gods and goddesses, secular subjects, mythical and literary images, erotica, and depictions of real scandals. It is a documentary of a city growing and a century, and a commentary on the social, religious, and economic conditions that were in flux at the time.

Extended wall labels are available for each section, but one is bound to hunger for more. While the show itself may satisfy the visually inclined, those more interested in the depths of research and references can look for the catalog by Aditi Nath Sarkar and Shatadeep Maitra that was published by DAG, and is available through their website.

It is evident in the production of this show how incredible their team must be. The installation, the lighting, and all other technical aspects of the show are as good as you can expect in a space that was once a British colonial prison. Keeping in mind that the space was once used to jail political prisoners, and has never been concerned with the nuances of displaying archival art collections, DAG has truly been able to transform the space and bring forth its greatest potential for exhibitions. It is also of note that the famous Kalighat is only five minutes away.

DAG proves yet again it is a beacon for the Indian art world, and an undeniable pillar in the realms of cultural research and exhibition making. The exhibition will run till 3rd January 2026.

Contributor