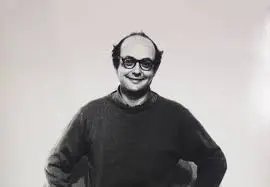

Today marks what would have been the 97th birthday of Solomon “Sol” LeWitt, the revolutionary American artist who fundamentally changed how we think about art creation and authorship. Born on September 9, 1928, LeWitt passed away in 2007, leaving behind a profound legacy that continues to influence contemporary art.

LeWitt’s path to artistic prominence was far from conventional. After experiencing European Old Master paintings during his travels and serving in the Korean War across California, Japan, and Korea, he settled in New York City in 1953. His early years were marked by diverse experiences that would later inform his groundbreaking work: studying at the School of Visual Arts while working at Seventeen magazine creating paste-ups and mechanicals, spending a year as a graphic designer in renowned architect I.M. Pei’s office, and working nights as a receptionist at the Museum of Modern Art.

These varied experiences, combined with his discovery of 19th-century photographer Eadweard Muybridge’s sequential studies of motion, shaped LeWitt’s unique artistic vision. The influence of systematic design thinking and seriality would become hallmarks of his revolutionary approach to art-making.

Pioneering Conceptual and Minimal Art

By the late 1960s, LeWitt had emerged as a founding figure in both Minimal and Conceptual art movements. His preference for calling his three-dimensional works “structures” rather than “sculptures” reflected his interest in systematic, logical approaches to form-making. Beginning in the 1960s, he created serial sculptures using modular squares arranged in patterns of increasing visual complexity. LeWitt’s theoretical contributions were as significant as his visual works. His influential essay “Sentences on Conceptual Art,” published in 0 To 9 magazine, became one of the most widely cited artists’ writings of the 1960s, articulating the relationship between artistic concept, execution, and criticism.

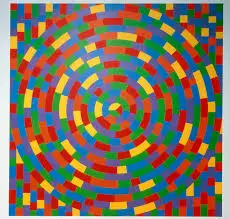

Perhaps LeWitt’s most revolutionary contribution to art was his wall drawing practice, which began in 1968. These works challenged traditional notions of artistic authorship and permanence. LeWitt would create sets of guidelines or simple diagrams, but the actual drawings were executed by others—first in graphite, then expanding to include crayon, colored pencil, and eventually vibrant washes of India ink and acrylic paint.

“Each person draws a line differently and each person understands words differently,” LeWitt observed in 1971, acknowledging the collaborative nature of his process. This radical approach meant that while he conceived the work, teams of assistants brought it to physical reality, creating subtle variations with each installation.

Between 1968 and his death, LeWitt created more than 1,270 wall drawings. These works embody a fascinating paradox: they are both permanent (as concepts) and ephemeral (as physical manifestations). Typically existing only for the duration of an exhibition before being destroyed, they can be reinstalled anywhere, adapting to new spaces while maintaining their essential proportional relationships.

LeWitt’s prolific output extended far beyond wall drawings to encompass over 1,200 executed wall pieces, hundreds of works on paper, and monumental outdoor structures ranging from towers to pyramids. His work spans from intimate book-sized pieces to gallery installations to massive public sculptures. The artist’s influence continues to grow posthumously. The first comprehensive biography, “Sol LeWitt: A Life of Ideas” by Lary Bloom, was published by Wesleyan University Press in 2019, cementing his place in art history. His wall drawings continue to be created by new generations of artists and assistants, ensuring that his innovative approach to collaborative art-making remains vital and relevant.

LeWitt’s legacy transcends any single medium or movement. His systematic approach to art-making, his questioning of traditional authorship, and his embrace of collaborative processes opened new possibilities for how art could be conceived, created, and experienced. On what would have been his 97th birthday, we celebrate not just an artist, but a visionary who expanded the very definition of what art could be. His work continues to be exhibited in museums and galleries worldwide, inspiring new generations of artists to think beyond conventional boundaries. Sol LeWitt’s true masterpiece may well be the conceptual framework he created—one that continues to generate new works and new ways of thinking about art long after his passing.

Featuring Image Courtesy: The William Records

Contributor