Betye Irene Saar, who turned 99 on July 30, is a strong voice in American art. She is known for her politically charged, spiritually rooted, and deeply personal assemblage works. Saar is respected not just for her unique visual style but also for changing what it means to be a Black woman artist in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Born in 1926, Saar started her career in social work before moving into the arts. She initially studied design at UCLA. However, a printmaking class during her graduate studies changed her direction toward fine art. Saar describes this moment as her start into a lifelong journey exploring symbolism, ancestry, and activism.

Saar was greatly influenced by sculptor Joseph Cornell and folk artist Simon Rodia, whose Watts Towers made a lasting impression on her as a child. She began collecting everyday objects rich in history and racial meaning. In the 1960s and 70s, as the Black Arts Movement grew, she created assemblages that challenged racist stereotypes and reclaimed Black identity, womanhood, and mysticism on her own terms. Her breakthrough work, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972), transformed a derogatory mammy figure into a symbol of defiance. This piece remains one of the most iconic works in American contemporary art.

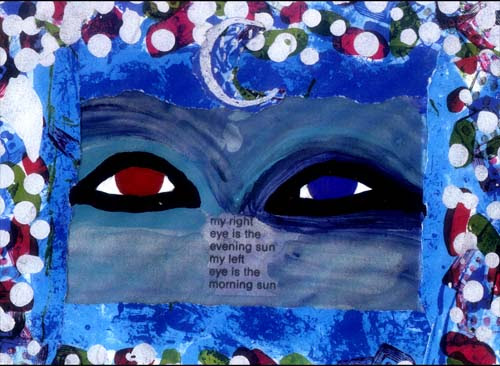

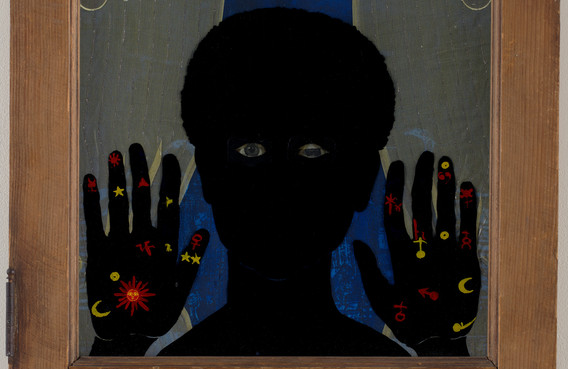

Saar’s work focuses on materiality. She combines prints, etchings, photographs, relics, and personal mementos to tell stories about ancestry, spirituality, and resistance. In Black Girl’s Window (1969), she constructs a haunting scene using a salvaged window frame, symbols of the cosmos, and her own etchings to portray Black girlhood shaped by both trauma and transcendence.

As her career progressed, so did the size and purpose of her work. Saar began creating immersive, room-sized installations that drew on African traditions and often encouraged public interaction. These ritual-like spaces included shrines and sacred objects, linking personal experiences with collective history and blending the mystical with the political.

Saar’s influence spans generations. She has exhibited alongside her daughters, Alison and Lezley, who are both artists. Her work is part of major collections, including MoMA, the Walker Art Center, and LACMA. Despite her recognition, Saar remains committed to storytelling and activism. “I still make art incorporating the same themes I started with: ancestry, mysticism, racial injustice, beauty, family,” she has said.

Saar’s work resists simple interpretation. Instead, it invites viewers to confront their emotions, beliefs, and biases. Her art is not just to be looked at; it is meant to be felt, questioned, and remembered. As art history continues to expand to include voices that were historically marginalized, Betye Saar exemplifies the power of persistence, memory, and material. At 99, her legacy is not just lasting; it is still evolving.

Featuring Image Courtesy: Mystic with Self Portrait, Image Courtesy: Mutual Art

Minerva is a visual artist and currently serves as a sub editor at Abir Pothi.