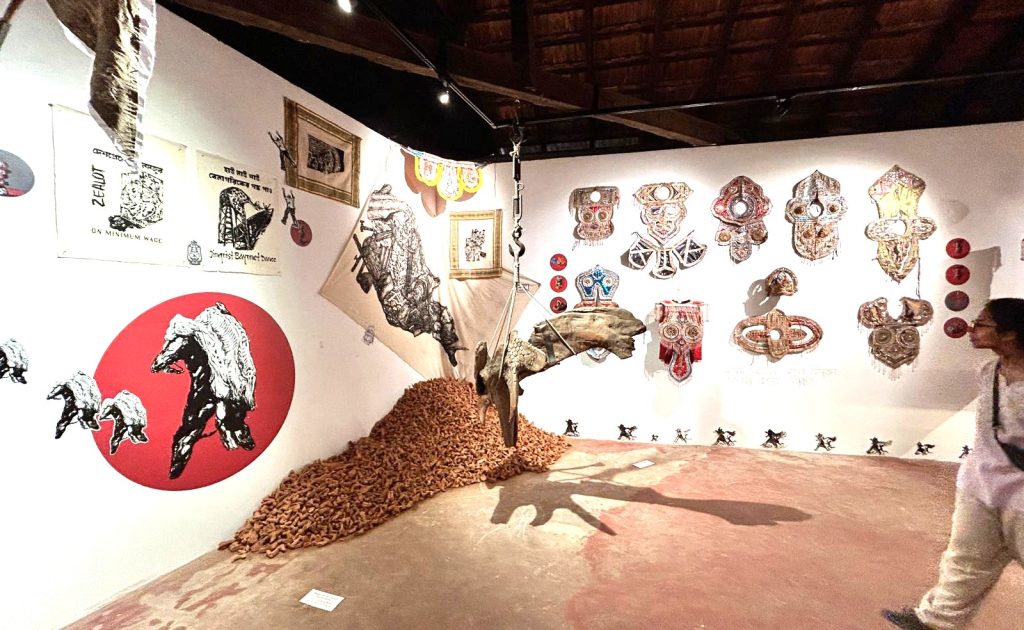

The Panjeri Artists’ Union is an anti-caste art collective based in Banipur, West Bengal, through their project, ‘Assemblies of Hope Amidst the Death-Worlds: A 100-Day Work Proposition’, which is a central highlight of the 6th Kochi-Muziris Biennale (2025–2026). This project, set up at the front of the main venue, Aspinwall House, is an ‘assemblage’ that points to this era and its ‘shady’ incarnations. It critically examines and artistically educates contemporary audiences about caste and its various articulations.

Panjeri Artists’ Union, a 14-member anti-caste art collective formed in 2021, is located in Uchu Amtala, West Bengal, on the India-Bangladesh border, and their representation in this biennale deserves attention, particularly as a group working from a region shaped by the consequences of the 1947 partition. While, as we know, borders are not merely spaces of conflict, members of the Panjeri Artists’ Union focus on ‘border realities’, including continuous surveillance, restricted movement, violence under security regimes, and disputes over shared rivers such as the Ichamati. Across multiple layers, this collective project explores how both countries, their borders, the people living there, and even the concept of ‘border’ itself have shaped their lives in ways they may not even be aware of.

Since the collective comprises artists from fields such as visual arts, design, literature, cinema, photography, and music, this project at the biennale showcases the collective’s diverse world. It is in those worlds, in the worlds of diversity, that the artist union conveys what they have to say. People in many places also see this collective as a bridge to many other areas, or as something that happens naturally. Even though they are from many places, what brings this collective together is a shared set of issues—displacement, migration, famine, and war—that people living in the same epoch share.

Even though we are living in a complex time, the world’s complexity cannot be seen in the art of this collective. Here, art functions as pedagogy; its primary mission is to make those living in this time aware of their era. This art group considers this mission as their duty and, fundamentally, as their primary responsibility. This activity, as a form of political resistance, progresses through media such as discussions, performances, workshops, and publications, engaging with the public and even incorporating opposing voices. The awareness that one can express what needs to be said through art, dialogues, and performances, along with the content to be expressed and its political context, makes this project noteworthy.

The ‘art activism’ of the collective is aimed at fostering a self-aware public through popular interventions in public spaces and institutions. Public spaces are a significant aspect, meaning the exhibitions of this collective take place outside galleries. The critique that the gallery-oriented art world prioritises commercial interests is, in general, an internal critique, directed against art itself. A continuation of these critiques can be seen in the collective’s art activism. However, art is not always a political activity, nor should one assume that all forms of art are, in some way, political. It’s not about everyone doing propaganda art, but the issue arises when everyone engages in ‘capitalist art’ and does ‘propaganda art’ within that. Both are different matters.

Ideally, this collective is a political voice against caste and, at the same time, gallery-oriented, capitalist art. This does not mean that everyone in this collective is always against galleries or completely turns on the capitalist side of art. However, it suggests the possibility of a political move opposed to it. “Other industries have unions. Art should too, so artists can organise themselves politically,” says Anupam Roy, who is part of this art movement. It is clear from this that one of the primary objectives is to establish a union for artists, just as a workers’ union. “Today, we should make poems including iron and steel. And the poet should also know how to lead an attack,’ once said Ho Chi Minh. At certain times, this refers to the qualities or actions people in the ‘artist’ category should possess or engage in. Sometimes you will have to pass through propaganda, art and beyond. This propaganda art exists in a leftist milieu. Exploring and investigating the worlds of art beyond aesthetic experiences is characteristic of the artistic inquiries of left-wing ‘socialist art’ or propaganda art.

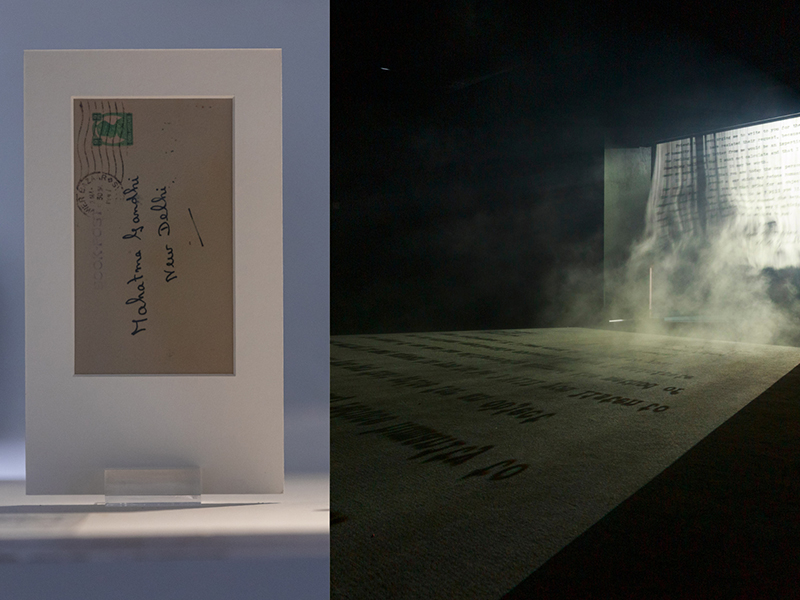

As you walk through the Panjeri artists’ exhibition, you will be greeted by walls filled with protest posters and slogans, including texts by Indian social reformers, Dalit thinkers, and political poets. They feel like the ‘walls’ of a college filled with children who boldly express their views, full of political slogans. Notably, the collection includes references to the famous poetry of Poykayil Appachan, a Dalit emancipator and renaissance leader from Kerala.

“No, not a single letter is seen

On my race

So many histories are seen

On so many races”

–Poykayil Appachan (Tr: Ajay Sekher)

The effect created by the above lines, as part of this exhibition, goes beyond introspection on a ‘race’. The artist aims for propaganda and, along with that, incorporates the thoughts of social reformers, including Poykayil Appachan, giving it a reformist aspect and an artistic action intended to bring about social change. It calls for a renaissance, emphasising the need to create spaces that include everyone—a world where everyone’s voices are heard loudly, and this is what this artwork openly declares.

The most appropriate way to understand this artwork is through assemblage: an entity that combines many components, such as multiple people, places, languages, methods, and disciplinary practices. It unites ‘multiplicities,’ creating ‘varieties’ of meanings, bearing its sociality. ”An assemblage is precisely this increase in the dimensions of a multiplicity that necessarily changes in nature as it expands its connections”, What did Deleuze intend by saying this? Dimensions are formed by connecting to many and disconnecting from many, and the ‘multiplicities’ thus formed create an equally ambiguous space; as it expands its connections, it simultaneously becomes a place where many can enter and exit freely, a place through which many can traverse.

A person’s thought is converted into artwork, which connects with another person’s creation and the worlds of meaning within it. Thus, assemblage operates here as the creation of worlds that have passed through numerous engagements and continue to evolve. If we understand this artwork itself as an assemblage, the ‘dimensions of a multiplicity’ are the diversities of the artistic worlds contained within it, which necessarily change in nature, because the created assemblage (this artwork) expands its connections as always. Every ‘view’, every engagement is turning into a ‘work of art.’ If an assemblage is a complex work of art, it can expand its connections and serve as a bridge to the audience, like a lingering feeling or an imprint.

The word ‘Panjeri’ comes from a Bengali term for the instruments sailors use to navigate through tumultuous, abruptly changing waterways. Through this word, along with its semantic worlds, the artist group both weaves and resists the turbulence of the time. In this way, a collective form emerges that is simultaneously enigmatic and political. The signs of time may indicate that this collective has things to say and has found a methodology to express them. Even though art is their chosen medium, how they shape it, turn it into assemblages, and imbue it with intense political action transform this collective.

The atmosphere of dialogue, highlighted as the main currency of this collective, is created through this work. A hundred days of a dialogic atmosphere might have an impact even greater than the art they present. This art creation, which intertwines numerous subjects such as the history of maritime trade between Bengal and Kerala, peasant uprisings, and anti-caste struggles, presents another world of art, offering a slightly more politicised model. As part of neoliberal policies, this collective has taken on the mission of bringing various problems faced by minority communities into these ‘dialogue spaces.’ Issues like the collapse of the agricultural sector no longer attract artists’ attention. Galleries will never allow artists to direct their focus toward such problems. Just as one can sell fabricated grand forms, one cannot sell mirrors held up to society.

Since conversations are its essence, those who encounter this artwork will experience its spark. At various points, it tells the story of protests and resistance. In that sense, this artwork can be called an archive of resistance, or of demonstrations, or a history of politicised rings.

Krispin Joseph PX, a poet and journalist, completed an MFA in art history and visual studies at the University of Hyderabad and an MA in sociology and cultural anthropology from the Central European University, Vienna.