Annelise Albers (12 June 1899 – 9 May 1994) is widely regarded as the most influential textile artist of the 20th century, an innovator who transformed the ancient craft of weaving into an art form in its own right. Born in Berlin to a middle-class family, Anni displayed an early passion for art, which eventually led her to the Bauhaus, the progressive German art school that championed the integration of art, craft, and design.

At the Bauhaus in Weimar, which she joined in 1922, Anni met her future husband, the painter and influential Bauhaus master Josef Albers. While Josef worked primarily with glass and metal before later specializing in painting, Anni turned to textiles, a field often dismissed as “women’s work” at the time. Her determination and experimental spirit helped redefine weaving for the modern age. She explored the interplay of natural and synthetic fibers, geometric abstraction, and innovative techniques that brought fresh relevance to tapestry and textile design.

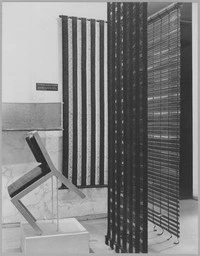

After marrying Josef in 1925, the couple moved with the Bauhaus to Dessau, where Anni took charge of the weaving workshop and created important commissions such as hangings for the Bauhaus “master house,” designed by Walter Gropius. When the Bauhaus was closed by the Nazis in 1933 labeled a breeding ground of “degenerate art”, Anni, who was Jewish, and Josef emigrated to the United States to escape persecution.

In America, the Alberses found new ground for experimentation at Black Mountain College, a radical, Bauhaus inspired institution in North Carolina. There, Anni taught textiles while Josef explored color theory and the perceptual effects of black and white. Together, they helped shape the next generation of American modernists, mentoring artists like Robert Rauschenberg and John Cage. Anni continued to develop her techniques, blending traditional hand-weaving methods with modern materials like cellophane, raffia, copper chenille, lurex, corn, grass, horsehair, and metallic threads pushing the boundaries of what textiles could do.

In 1949, Anni Albers made history as the first textile artist to be awarded a solo exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, a landmark moment that cemented her status as a pioneer. The same year, the couple left Black Mountain and settled in Connecticut, converting their home into a studio where Anni continued to innovate. Her design for Philip Johnson’s Rockefeller Guest House, a drapery woven with metallic threads to reflect light, exemplifies how she merged art with architecture, turning fabrics into integral parts of built spaces.

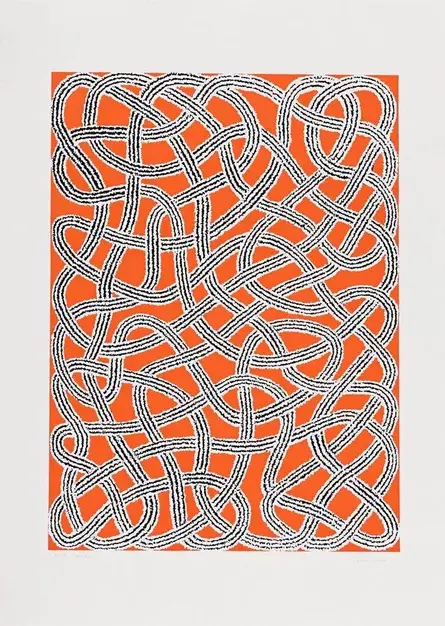

Despite her achievements, Anni often felt her work was undervalued compared to that of her husband and her peers in the so-called “fine arts.” She was deeply aware of the rigid divisions that still defined art and craft, once writing, “I find that when work is made with threads, it’s considered craft; when it’s on paper, it’s considered art.” Yet her prolific output including major works of textile design, jewelry, prints, and influential books like On Designing (1959) and On Weaving (1965) challenged those divisions at every turn. In the 1960s, Albers turned her attention to printmaking and drawing, yet even these later works echo the grid structures and linear forms of her woven textiles. Exhibitions at the Brooklyn Museum, the Renwick Gallery, and the Yale University Art Gallery in the 1970s and 1980s continued to highlight the breadth and depth of her legacy. Recognitions followed: in 1990, she received honorary degrees from the Royal College of Art in London and the Rhode Island School of Design.

Today, Anni Albers’ influence resonates far beyond the loom. Her groundbreaking approach to weaving and design continues to inspire contemporary artists and fashion designers alike, from Karla Black and Phyllida Barlow to Roksanda Ilincic, Mary Katrantzou, Duro Olowu, Grace Wales Bonner, and Paul Smith. Designers and artists still collaborate with the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, ensuring her ideas live on. A quiet revolutionary, Anni Albers proved that textiles are more than functional objects, they are canvases for modernism, capable of transforming spaces and perceptions alike. As Tate Britain’s recent retrospective confirmed, her legacy is not just that of a master weaver but a true modernist visionary whose work continues to shape art, design, and craft for generations to come.

Featuring Image Courtesy: Apollo Magazine

Contributor