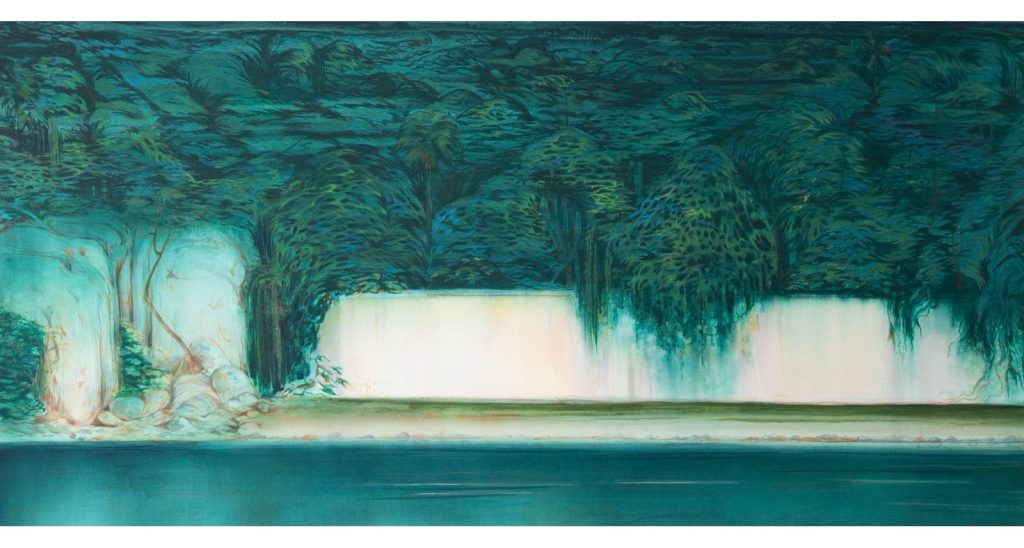

One among the art productions that is attracting a lot of spectators in the initial days of the 6th edition of the Kochi Muziris Biennale is the young artist Sujith SN’s painting series titled Untitled (2025), Elsewhere or Otherwise (2025), and Gateway to the Botanical Gardens (2025). Through this painting, the artist aims to create an atmosphere that is both time-bound and timeless, universal and personal.

In aesthetics, the concept of ‘Atmosphere’ is proposed by the German philosopher Gernot Böhme, which suggests that beauty can be seen as the creation of an atmosphere, or that an atmosphere can create beauty. In the context of art, the idea of atmosphere is both powerful and engaging. Although Böhme’s concept is primarily applied in architecture, design, and events, it is also evident in art, particularly in the aesthetics that create its atmosphere. Whether it’s a music night, drinking beer in the dim light of a bar with a friend, a wedding house, the aroma that wafts when biryani is served at a wedding, or the celebration of a church festival, the ‘feel good’ experience they create can, in a way, be described as an ‘atmospheric’ experience; it’s an experience provided by that place. That place, upon reaching there, is the arrival at that feeling, a journey towards happiness and the states that experience offers primarily.

Art plays a crucial role in providing this experience. When we discuss an exhibition like the Biennale, it is never a wedding or a festival; yet, Böhme’s idea that ‘the atmosphere of a certain environment is responsible for the way we feel about ourselves in that environment’ is applicable here. The Biennale is both an event and an exhibition, and it can be viewed as a large exhibition comprising many smaller exhibitions, each of which can be considered a distinct unit. Each piece of art presents a vast world in its own way. In that sense, every work of art can be seen as a conceptualisation of a larger world.

‘Atmosphere’ is explained by Böhme as ‘atmosphere is what is in between, what mediates the two sides.’ That is, it functions as a component that unites two things—people and the atmosphere they are in—implying that the atmosphere is an important entity. At the same time, when considering a work of art as an ‘atmosphere,’ it should be seen similarly: as an atmosphere that exists in the art, the atmosphere created by the exhibition of art, and beyond that, the atmosphere that is produced within it, thus forming a collection of various types of atmospheres. As a way of thinking, an artistic creation can be said to be an ‘atmospheric’ creation. It can be described either as a creation of a way of thinking or as a creation of an atmosphere. That’s why we can see that the ambiguity is the soul of an artwork, and interpretability is its first cousin.

The artworks of young artist Sujith SN displayed at the Biennale engage in a specific ‘atmospheric’ intervention. They are a continuation of the view of the ‘Botanical Garden’ in the desert that he saw during his journey in Egypt, or rather, the artist transforms that visual experience into a space that also incorporates the history of Hortus Malabaricus, reflecting, in a particular way, the idea of art ‘for the time being’, advancing the Biennale. Since Hortus Malabaricus serves as a conceptual framework for these paintings, the colonial period and its historical context make the surroundings of these artworks both time-bound and era-specific. The concept of eternity is either time-bound or stamped. Nothing exists without time. Seen in that way, these paintings are both eternal and also remain as a reflection of the “time being” at the same time. They go beyond time and create an atmosphere that the spectator perceives in either way.

Through the paintings, displayed under three titles, Sujit presents a vast history and era in a very minimal way. No one can mute time when creating art. Even if one thinks about it, it is impossible to mute time when making art; in short, time is either the spirit of art or its backdrop. In that sense, a work of art is also a creation of its time. However, it is possible to represent time abstractly. A work of art can merge multiple kinds of time simultaneously, making the artwork a hidden refuge for the mystery of time. Seen in that way, this artwork marks various types of time. In that sense, this artwork can be considered eternal. The paintings are displayed under three titles: Untitled (2025), Elsewhere or Otherwise (2025), and Gateway to the Botanical Garden (2025). These titles present three layers of the historical narratives of memory in the exhibition. The idea of a botanical garden seen in the desert later visually evolved. With the addition of the text Hortus Malabaricus, it opens up possibilities for meaning-making across multiple layers, which can be described as both mysterious and timeless.

Sujith’s paintings convey the idea that vision is the creation of another world, which could also be a construction for another time. Deleuze discusses becoming, stating that ‘becoming does not tolerate the separation or the distinction of before and after, or of past and future.’ The space of an artwork is like an intersection between the past and the present. It is ‘becoming’ precisely when it is ‘atmospheric.’ An artwork is transforming into something else, into many things, into another being. The artist narrates the two states of the botanical garden here in two colour schemes. In one, there are various states(shades) of green—a state where green has turned melancholic. Otherwise, green is depicted in long-term colonial languor. The overlay of melancholy makes their inner meanings mysterious. A dreamy landscape that expresses the green’s pursuit of its mysterious meanings, its urgency and capability to spread beyond colonial limitations. Yet, certain elements that make things even more mysterious—the green of various trees, some of which seem ancient and others hanging expansively—make the greenery even more enigmatic. What resonates through the symbol of introspection should not be limited to meditation alone; here, the greenery not only adorns the trees but also, beyond calling forth the grandeur of a botanical garden through its colour, takes a journey into colonial interpretations through the conceptual framework of Hortus Malabaricus. The underplay of time, history and the personal is intertwined here. That’s how the atmosphere becomes relevant. The first one is the artist’s reply to the oppressive and binding colonial period. The horthus malabaricus pre-text is nothing but his expression of figuring out and, at the same time, breaking away from coloniality. The white wall, which is actively limiting the growth, is visible, and it clearly represents the “all-encompassing white sentiment”.However, the greenish flora and fauna growing within it are expanding beyond its boundaries. So the notion of boundary is in question here. An artist here is experiencing and experimenting with history, which now becomes a personalised narrative of history. According to the artist’s spectacle, the post-colonial world is the greenery within, which is outgrowing and outshining the white exterior. Here, the history becomes personal. The binary opposition of official and personal is what makes the first painting attractive.

Elsewhere or Otherwise (2025), when it comes to the artist’s direct experience of introspection, Hortus’s works are different because of their historicity. That is, these paintings also serve as reflections of the artist’s history, which in turn reflects the history of the landscape. There is one view within another view. That is why each view exists anew. There is a view that the artist has seen somewhere at some times. When it becomes a painting in front of the viewer, it evokes, rather than that view, some other views that have been muted before us. Beyond fixity, muted spaces reveal themselves.

There are no humans in the compositions. When we say there are no humans, it only means there are no humans in the sense of a physical body. However, human actions are present. Just as colonialism becomes the history of the cruelty of the ‘white man,’ it is also the ‘oppressed’ history of the black man. Through compositions that include neither the oppressed nor the oppressors, only through trees, under the name of a botanical garden, all that has been forgotten is being brought back. It serves as a reminder that nothing has truly been forgotten. These paintings suggest that if anything is forgotten again, it will continue to be remembered through the art practice. Through these paintings, the artist is rereading history. In the rereading of history, many things that were unread before are now read. It should also be remembered that even in the oral history of Hortus Malabaricus, the harm of deceit has been prevalent. Seen in this way, these paintings are a re-narration or rereading of the history that is spoken of and well known- this is where time intervenes.

When we read history, the wounds hidden in it surface. If we ask whether art applies medicine to those wounds or exacerbates them, there is no answer. It is not the creation of an answer but the relevance of the question that matters. It is while stating that the question remains relevant even without an answer, and that its paths are mysterious and secretive, that artistic activity engages with that time and with the people of that time. Post-colonial is a condition. Nothing can be removed from its radar. Post-colonial narratives are not implemented by removing anything. The Biennale also takes place in warehouses and other spaces that can be described as the leftovers of colonial capitalism. In that sense, the Biennale is entirely a post-colonial narrative. However, within the post-colonial narrative of the Biennale, which can be considered a giant, Sujith SN’s paintings can be seen as another post-colonial narrative. The lesson that there are small worlds within the larger world, and that these small worlds also encompass the larger worlds, is changing both as a lesson and in its interpretation. These paintings testify that we are never a muted people and sometimes silence is given new scales, sometimes symbols, and at other times meanings.

Cover image: Sujith SN | Gateway to the botanical garden – Diptych – 71 x 34.5, 71.5 x 34.5 – Tempera on Arches paper – 2025.

All images courtesy of the artist

Krispin Joseph PX, a poet and journalist, completed an MFA in art history and visual studies at the University of Hyderabad and an MA in sociology and cultural anthropology from the Central European University, Vienna.