At the 6th Kochi-Muziris Biennale (2025–26), Indonesian artist Jompet Kuswidananto presents ‘Ghost Ballad,’ a site-specific installation at Pepper House, marking the journey from dictatorship to democracy and bringing together once-thriving, banned music and performances. The work uses his signature objects of ‘bodiless’ figures to gather the fractured chronology of Indonesia, acting as a bridge between the Malabar Coast and Java. There emerges, through this artwork, a connection among Indonesia, the Malabar coasts, and even Goa, which may sound like a ghost story, and it’s a musical one at that.

The installation is an introspection of how culture endures through ‘transmutation’—from authoritarian repression to colonial subjugation, and ultimately to a precarious democracy. It is here that one comes to understand that the music, drama, and sounds included are all forms of representation, reflecting it, sounding it. These ghosts are the ones who sing. Their songs not only carry nostalgia about their land. Those songs encompass both that region and other areas connected to it. The exchanges between the Fado music tradition brought by Portuguese sailors and slaves who arrived in Indonesia in the sixteenth century, and the Keroncong music style from the soil of Java, along with the musical styles that emerged from them, created a space for cultural exchange within Indonesia. The music that emerged from these two styles, and some of the songs within it, has immense potential to influence the Indonesian people. These long-voyaging musical forms later crossed the seas again, reaching as far as Goa, along with their history, awakening artistic audiences there, as Kuswidananto does.

Note a point, through trade, forced migration, and military routes, Fado traversed the Portuguese empire. It became Mando in Goa, Cafrinha in Sri Lanka, Branyo in Malacca, and Keroncong in Java as its emotional structure spread throughout Asia. That is, as a musical backdrop to Portuguese conquests, Fado has taken root in many parts of the world. Kuswidananto states that this composition has created such a musical link.

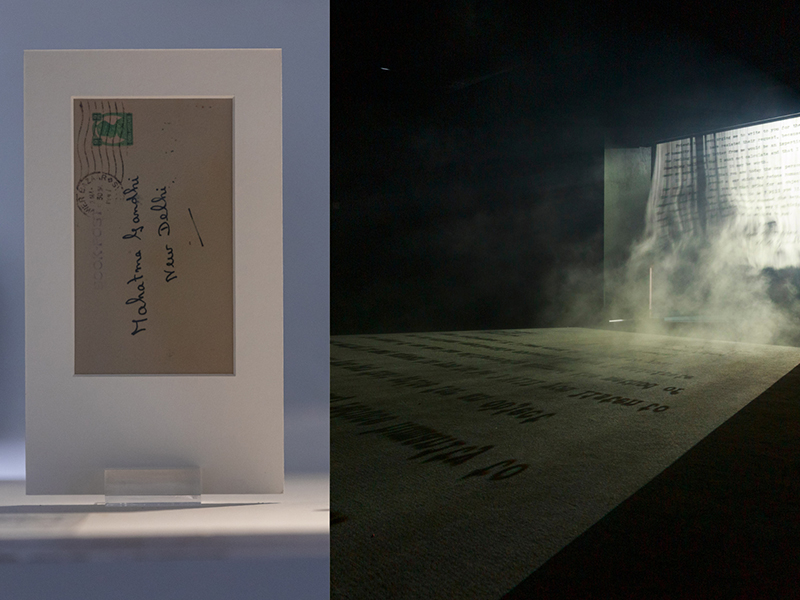

The history addressed in the work ‘Ghost Ballads’ begins from the colonial period. Over it, the cruelties and aggressions during Suharto’s rule are reflected, along with the journey from dictatorship to democracy. It is formed through videos, sounds, and other elements, with voice, performance, found materials, and various materials coming together, including dresses from Kochi and the artist’s hometown. In this way, the political and social contexts this installation raises are shaped.

The performance element in this installation comes directly from the artist’s long-standing relationship with the theatre group in their hometown. Through this, the artist brings forth many invisible sounds and traditions from Java’s tainted history. All of these converge into a world that elevates ‘Ghost Ballad’ into another realm, a world simultaneously of entanglements and coexistence. While colonialism and imperialism represent two sides of the same coin, it is characteristic of colonialism itself that many things, including Fado music, come through that path. In this way, a ‘new’ world is created. It is within such a world that we examine the history of colonial invasions. And that, in itself, remains something ambiguous.

Here, the ghosts standing in a line like band players, the music and movements they sing, emit, or stand submerged in, along with the times referred to and their disasters, are sources of expressive performance that transcend them. The ‘ghosts’ standing here represent the spectrality of another era, the embodiments of a ghostly time, and their movements are filled with the flows of another period, its music, and the silences within it. However, this work is not about music itself; what is conveyed through music are other matters—markers of power that transcend time and are reflected in everything around. The music referred to here, seen as a continuation of colonialism, must be understood differently in terms of the issues it encountered during the post-independence period, including suppression. This creation acts as a pointer towards reading that era as well.

The artist says, “The hollow bodies reflect the historical absence of the people who carried these songs.” This is where a song searches for its singers, searches for those who used to sing it. The echoes it creates, the unrest, stretch back to that time as well. The song survives, but where have the singers disappeared? What kind of time was it when that song was banned? What did the song do to be banned? Apart from all that, that bittersweet song, even if it was just about the sea, fills this place with many questions and doubts. Many songs have survived through the efforts and engagement of ordinary people. Without recording names, they can be called oral, grown, and evolved branches of songs, even going back to bygone times, like Fado and Keroncong. Therefore, apart from the song itself, neither its writer nor its composer remains. Only the song exists, filled with sorrow, brimming with history and memory.

The similarities between musical styles that developed in two countries during the colonial period were formed at that time; therefore, they constitute a historical record. The artist argues that the impacts of the colonial period and the resistances that arose from it are present in those songs. Even as background music for an artistic creation, these songs have an immense impact. This work of art testifies that a disembodied crowd can be more politicised than a crowd with both sound and body. Fado and Keroncong are classified as melancholic songs.

The Indonesian Minister of Information, Harmoko, famously banned this song from state television because its lyrics—about a woman’s heartbreak and domestic sorrow—were deemed “too gloomy” and “unproductive” for a nation focused on economic development. The song was banned because Melancholy hindered national progress; another reason was that it was considered un-heroic. Thus, songs that obstructed national progress were banned, and over time, these songs have returned as a form of art in their own right. What Kuswidananto has presented can be seen as ‘Melancholy as Resistance’ in its ghostly presence. Kuswidananto reclaims “sadness” as a political act by reloading the room with gloomy music. According to him, expressing grief and longing was a kind of “quiet resilience” throughout the tyranny.

The audience hears drumbeats, strumming guitars, and whispering voices that become audible only when they get close, establishing a close-knit, personal tie. The footwear positioned next to each figure suggests roots in native soil within the bigger frames, absorbed within; the floating bodies refer to migration and seafaring. Kuswidananto contends that Indonesia is in a state of perpetual transformation in a continuously shifting geopolitical environment. As a result, the “ghosts” stand for a flexible identity—a survival tactic in which individuals must constantly change who they are to conform to various political systems (from colonialism to dictatorship to democracy).

I think this work is remarkable for how it moves from colonial undercurrents to post-independence dictatorship, and, in between, shows all kinds of give-and-take, with history and background interwoven across multiple levels. When you see the ghostly figures lined up in the exhibition hall, pay attention to whether you can hear the sounds and music. Viewed in this way, this ghostly speech/song can only be heard through careful engagement. The music, far from being melodious, carries a political tone that makes it both timeless and historic, contemporary and ancient, turning it into a post-colonial orchestra.

This Biennale has brought together numerous ghosts from various places and times. In a sense, post-coloniality is a kind of ghost language. Ibrahim Mahama’s notable work, ‘Parliament of Ghosts,’ enables a political-social reading that foregrounds colonial ghosts. The works in the Biennale examine multi-layered social environments, questioning how colonial ghosts shape them and what exists in these life circumstances within the imagination of post-coloniality.

Krispin Joseph PX, a poet and journalist, completed an MFA in art history and visual studies at the University of Hyderabad and an MA in sociology and cultural anthropology from the Central European University, Vienna.