In the context of the exhibition “പൊന്നുപോലെ/Like Gold”, curated by Meena Vari as a collateral event of the ongoing Kochi-Muziris Biennale, examines gold not merely as a mineral or currency, but as a site of intense emotional, material, and historical “transmutation.” ‘Like’ is an expression that can be attached to many things! A world created by the word ‘Like’, which is used to indicate similarity between one thing and another, like a poem, like gold, and so on, is being created here – a world that can be argued to be somewhat more semiotic, and yet political.

The term ‘Golden flows’ is a concept that connects places like Kochi and Malabar with other locations, notably across the Indian Ocean to the glittering megalopolises of the Arabian Gulf. Gold’s significance is not just that it acts as an interjection, linking longstanding global networks. Beyond that, as part of millennia-old networks of commerce, merchants and traders from as far away as Rome would exchange it for pepper and other spices. It was used to trade for many valuable items, as gold has always held intrinsic value. There was never a time when people did not strive to obtain it and become wealthy. This is a material history, a history of human adventure and survival. The practice of establishing dominance over gold was later monopolised by European empires, which would come to dominate this economic sphere and exploit it to amass colonial fortunes.

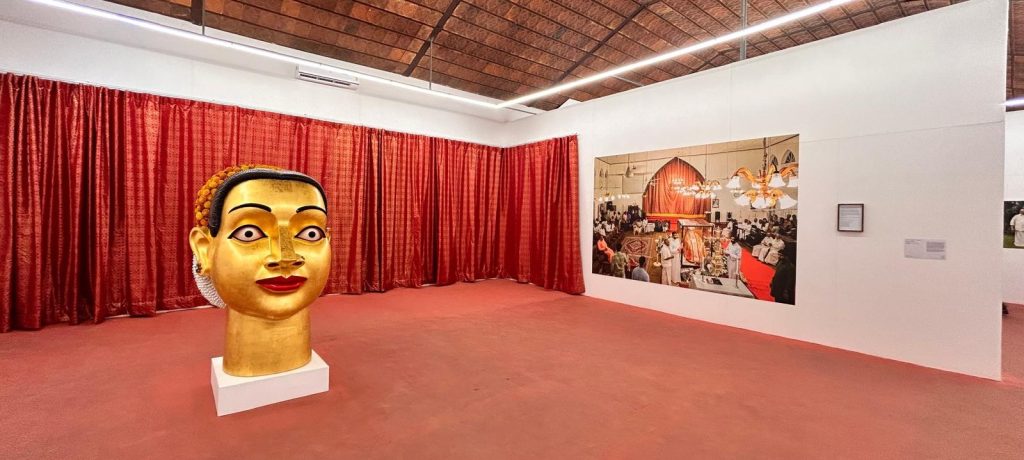

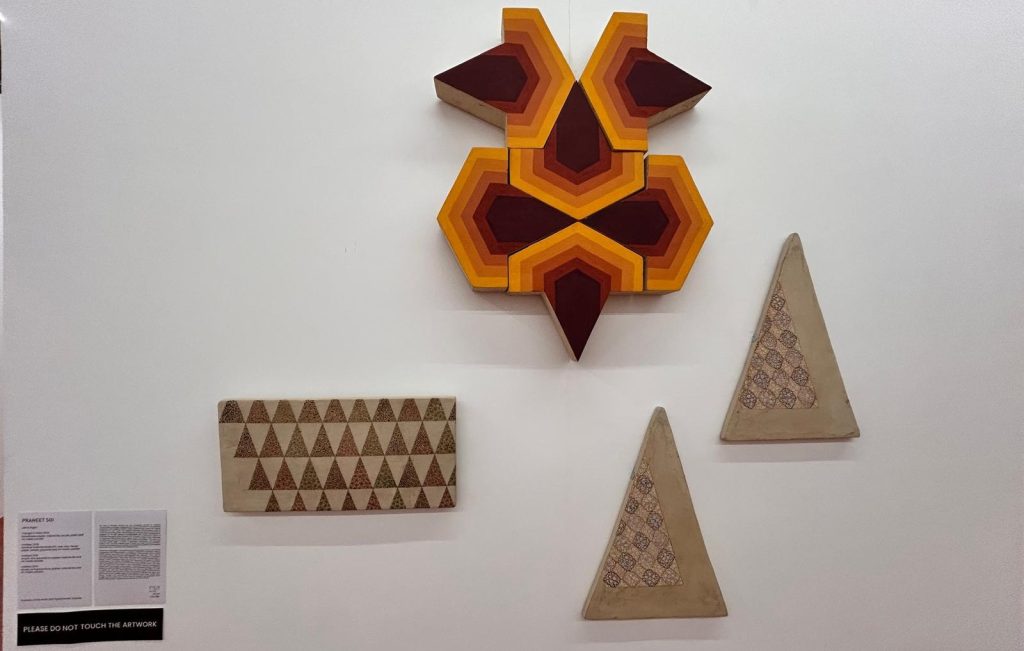

In this exhibition, which is extremely meticulous about thematic diversity, each artwork on display problematises the material ‘gold’ in various ways. Vivek Vilasini’s Gold of a Thousand Dawns (1995/2025) re-creates a lost work first exhibited at the Sharjah Art Museum in 1995. This creation connects multiple places and simultaneously represents and questions the artist’s spiritual-political inquiries. Ravinder Reddy’s work, Lakshmi (2019), while marking the religious centrality of gold, argues that its potential is political and social; within the embellishments, a ‘gold-faced’ sculpture easily establishes its dominance within a domain, and at this monumental scale, with its prominent eyes and intimidating, lineable gaze, Reddy’s sculpture emphasises darshan, the interplay of gaze between the divine.

Anup Mathew Thomas’s photographs highlight spaces where ‘gold’ is installed in Christian-Hindu places, marking the social idealisation of these spaces. Thomas’s Scene from a Wake (2016), from a series with the same title, focuses on an important event at the headquarters of the Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church in Thiruvalla, Kerala, on how to bring ‘radiance’ to a place illuminated by gold. The presence of gold in the images on display, intertwined with many others, is impossible to separate. Similarly, by bringing the kasavu—an emblem of Malayalis—onto the shoulder of a community leader, Thomas creates a place laden with questions. In this place, originality and nobility cannot be distinguished by anyone, and it marks the religious symbolisation of the place created.

When thinking about ‘gold’ in the Indian context, an unavoidable social reality is the practice of dowry. It is this social condition and social resistance that Varunika Saraf’s ‘Jugni’ series (2025) examines through her work. The artist decodes photographs of similar moments from protests into delicate watercolours enclosed by halo-like circles, adorned with tiny seed pearls and embroidered with gold thread, and placed against lavish fields of women’s gold. These intimate yet opulent works subtly challenge the gendered associations of gold, the value, worth, purity, and property as operationalised through the illegal but still widespread practice of dowry, by reworking a deotional format to center and celebrate women’s individual and collective agency and their crucial role as catalysts of social and political change as well as as champions of human rights and social justice.

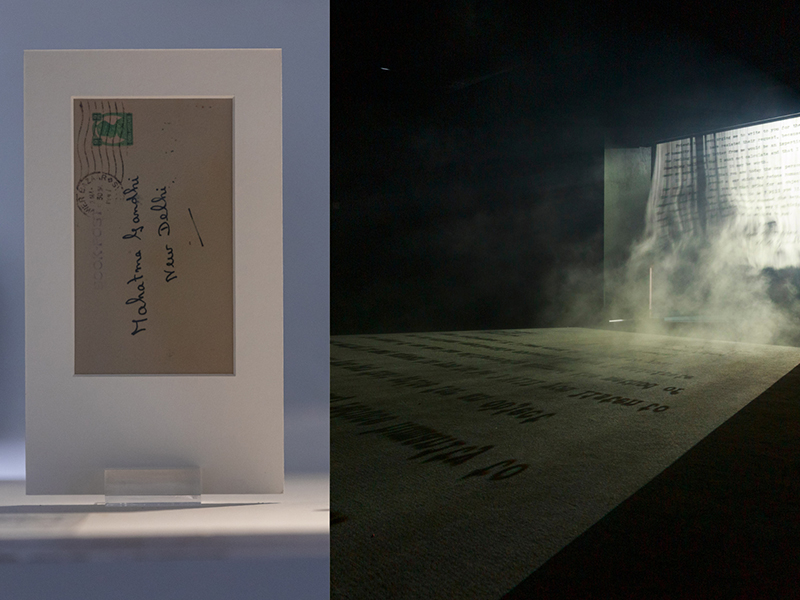

Cop Shiva’s Being Gandi (2012) is a character study of Bagadehalli Basavaraj, a school teacher in Kadur, rural Karnataka, who has long expressed his dedication to Gandhian philosophy through an astonishing act of self-transformation and role-playing. It is part of the artist’s longstanding interest in masquerade and performance. Indu Antony’s I Brought Her Up Like Gold (2021) marks another dimension of gold, and that connects to a popular Malayalam phrase that describes the loving but often excessive care that parents show their children. It has two meanings: unrealistic expectations and inevitable disappointments, as well as notions of commitment, support, and opportunity. A circular cyanotype, a vignette selected from family photos, and gold leaf are subtly adorned on each, creating something that marks time and examines the family’s position and current state.

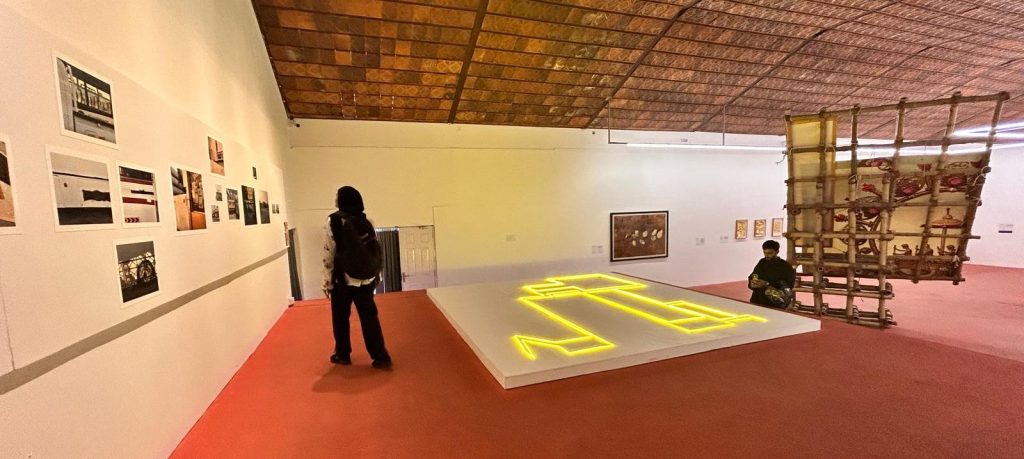

The 2017 piece Hemali Bhuta was created as part of an art residency in a former gold-mining region of France. Subarnarekha, the name of a river that flows across Eastern India and means “streak of gold,” was the subject of her display there, which connected two different landscapes through their shared gold histories. The Cage of Memories (2023–2025) by poet, artist, and filmmaker Nugoom Alghanem is reminiscent of the traditional Emirati dome-shaped fishing traps known as gangour, made from strips of dried palm fronds fastened together with buriap strings. Similar to Kochi’s well-known fishing nets, these artefacts transport us back to a time before oil was discovered, when people relied on the sea’s erratic abundance for food and time was governed by the tides and shifting seasons.

In short, the exhibition ‘Like Gold’ renegotiates its material history, a social history, and, beyond that, a history of various, mysterious, and often unrecognised forms of dominance that articulate in subtle ways. This exhibition simultaneously engages with or explores ‘gold’ as both myth and material. However, it is not only about telling the history of gold; instead, it seeks to trace the meanings that have evolved, circulated, and formed in society in connection with it. ‘Like gold’ explores the magical substance’s transactional and transmutational nature, and we can see that the show also takes us into philosophical questions about the value we assign to and find in an object.

‘To cherish you like gold’ is an expression used to convey the extent of care one person shows to another. Through many such expressions, gold has become a significant and influential part of daily life. The significance of ‘gold’, as developed over time through various transactions and interactions, including through language, is documented. There is a gleaming history behind this word. It conveys a history that depicts the often intense care and attention, both affective and material, lavished by a parent on their child. This exhibition presents a perspective that looks back at that history. Just as the presence of gold symbolises wealth and power, its absence symbolises ‘lack’ and social untouchability; that is, gold fills or empties a person’s world in terms of success and shortfall, pride and disappointment. The presence or absence of gold determines a person’s social position and can elevate or lower them. In that sense, gold is also a measure of social position. What is measured through that unit is social conditions, and the number of people who fear it is enormous.

The like highlights gold’s metaphoric and metamorphic capacities; it is not about establishing that gold is a unit capable of growth and decline, but instead moving through its various meanings. It’s near-universal use as a symbol of value, works, and purity, and the way these social and cultural associations work.

Through the second half of the twentieth century, the post-colonial Indian state’s imposition of substantial duties on gold imports catalysed the establishment of a shadow network of smugglers and intermediaries whose activities circumvented these restrictions. Looking at it that way, we can see that many parallel things have happened. Between the two countries, the material, gold, has sometimes created two types and, occasionally, many kinds of living conditions: legal and illegal, and wealth and deprivation. Gold and the golden era contributed to the financial success that led to Dubai’s emergence as a ‘city of gold’, a city whose souk, dedicated to the substance, anchors its historical urban core. This growing apparition has seduced waves of migrant workers to travel in the opposite direction in search of wealth and a better life, further entangling the fates, fortunes, and histories of the two regions.

Gold plays a significant role in South Asia’s cultural imaginaries and art histories despite the region’s limited natural resources. Its lustrous yellow colour and enduring shine have linked it to concepts of the sacred and the magical, as well as to associations with privilege, power, and status; in other words, gold can be said to have united various centres of power dispersed across different locations under its sphere of influence. It has been used to embellish religious icons and architecture. Since ancient times, gold has held a high position and been used for ornamentation, as well as to illuminate Mughal manuscripts and ornament lavish objects of decorative art. Through this, it shaped a ‘regal’ form of art. Across different religions, jewellery made from it—from a simple bangle to opulent gem-encrusted necklaces—features prominently in customs and rituals marking rites of passage, especially marriage. Looking at the history of art, it is the history of materials, including gold. It mediates between power and privilege, unites politics and the state, creates genuine bonds between individuals and families, and brings many things together.