Gulammohammed Sheikh for Abir Pothi

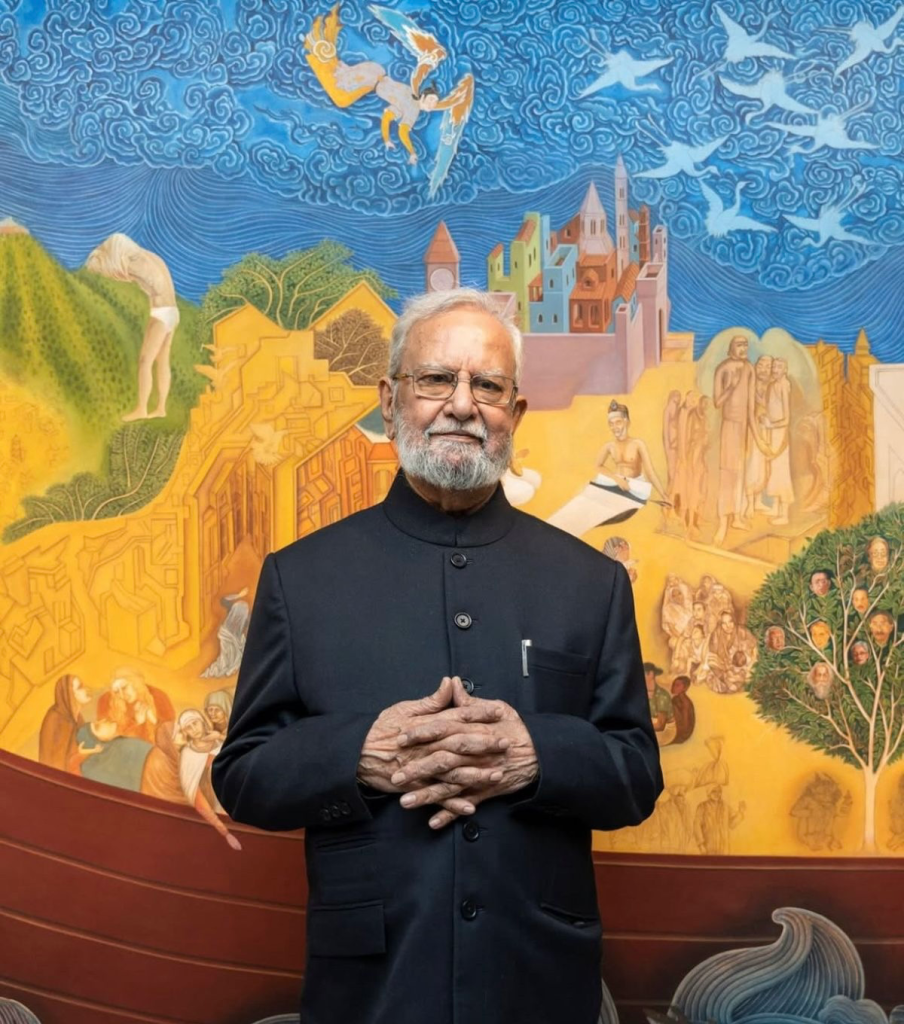

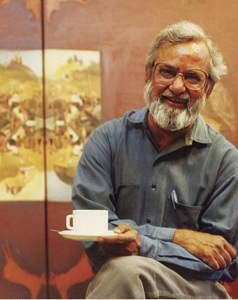

When Gulammohammed Sheikh’s retrospective opened at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in New Delhi in February, it was the grandest launch of an exhibition witnessed by many from the art fraternity in recent times. The reason was simple—such comprehensive exhibitions on the lifelong oeuvre of an artist who has had a stellar career of more than six decades are not just rare, they are also unique as the artist himself is present to speak about his journey over a career that has been informed by some epochal events in the life of this nation.

As people jostled for space at the already expansive museum at Saket, New Delhi, to get a glimpse of the artist and also his works, it became clear that one needed more than just the inaugural evening to soak in the lifetime’s work of this seminal artist of Indian modern art.

Even though getting a stretch of time with this revered artist was a torturous and long drawn out process, it was all worth the while as he gave an exhaustive interview on his current exhibition, and his career so far. Following are excerpts from the interview, where he speaks on his ongoing exhibition, ‘Of Worlds Within Worlds: Gulammohammed Sheikh, A Retrospective’, that runs through June 30, 2025, at Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, Saket, New Delhi.

Looking at your own works from several decades ago, what would you say about the evolution of your own art? Do you feel surprised while revisiting some of your paintings from decades long gone?

Any artist over a period of time would be partially surprised and also may feel curious about how these works came in this combination, as the curator has arranged them. There are a number of works that I hadn’t seen in several years. What she [Roobina Karode, curator of the exhibition] did, for paintings, prints and photographs while curating the show, indicates that she had made her mind about presenting the multiple media that I work in. In presenting this selection of 119 works, Roobina [director and chief curator, KNMA, and a former student of Sheikh] did a good job.

If you had the opportunity to go back in time to a period when you enjoyed painting the most, what would that be?

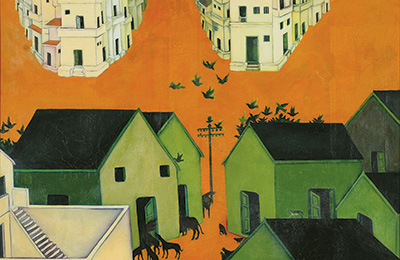

Each period has its own issues. You worked in a particular situation at that period of time, you perhaps chose a particular scheme or included some colours, which you may not in other period, for whatever reason. To cite an example, you must have noticed my paintings in yellow. That was around 1968-69. For a period of about three-four years, I made quite a few paintings of trees and mountains, which were more or less done using yellow. My favourite is cadmium yellow. I combined various yellows, sometimes cadmium on lemon or vice versa, all of which gave out luminescence of different hues. It was the different luminescence that I was most curious about while using those different yellows. These paintings, it seems, are basking in sunlight, they give out such luminescence. The idea of creating that light was to connect it with the sunshine in India, which is different in different seasons. So, in that sense, these paintings got connected to a season, not that I painted in that particular season. But, that is how these paintings came about.

One of the pleasant surprises of this exhibition is its presentation of your works in abstraction. Could you throw some light on your tryst with abstraction, in the prevalent preferences of the 1960s in which the use of impasto technique predominated? In this exhibition, your abstract works in impasto stand out for the hints of figures they carry, that seem to appear from behind the haze. You once shared that it was the influence of the Bombay Progressives that inspired you to take up painting in impasto. Could you elaborate on your sentiments of those times?

All my paintings have figures, whether abstract or not, at least in the sense in abstract paintings from that particular period of time. This refers to the time when I had just finished my masters, was about to have a one-man show, had three shows during that time. That was the time when tonga was commonly used. That’s where the painting featuring the horse came about. I’m just using a white animal, either tethered to the tonga, or wandering around. I remember that there was also a painting in which a horse kicks off the tonga! May be, that was a way of seeing at common place things—how when there is no tonga that it is tethered to, then the horse just wanders around…

Regarding the use of heavy impasto, I can tell you that those paintings were not done with brush but with a palette knife instead. And the kind of colour used—you must have noticed how different it is—was the kind that K.G. Subramanyan made for people who couldn’t afford to buy colours from famous companies, such as Newton. He had prepared a kind of a glue which was made by linseed oil boiled with a kind of a wax, and double boiled to produce a gel. That came in handy to young students who couldn’t spend much on paints. In those days, we would especially go out looking for the cheapest paints available, even in hardware shop, and Subramanyan’s inventiveness came in handy.

That is why those paintings are different from the rest as they carry an additional story of our ingenuity to use cheap colors and yet create what we wanted to.

Featuring Image Courtesy: KNMA

Read more of his interview here, Gulammohammed Sheikh talks about his process through the years!

Archana Khare-Ghose is a senior arts journalist, and a commentator on art, market, books, society and more